Bioclimatic urban design

The recently released 2021 assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is not encouraging.

It projects an average global temperature increase of 1.5 degrees beyond pre-industrial levels by 2030, a decade sooner than what the was originally estimated, pointing to an early depletion the carbon budget set in the Paris accord.

Global surface temperature has increased faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over the last 2,000 years. The increased warming will result in increased frequency and intensity of heatwaves and droughts, flooding and typhoons, agricultural and biodiversity losses—widespread effects that are likely to be more severe and lasting than the current COVID-19 pandemic.

While climate change is a global phenomenon, the impacts are felt locally. As such, interventions and adaptation will also need to happen at the local scale, and in particular, in the way we shape our local built environment.

Carbon impact

Buildings and other grey infrastructure account for almost 40 percent of annual carbon emissions worldwide, 28 percent of which are from building operations, while 11 percent are from embodied carbon in construction processes and building materials production.

The unprecedented levels of urbanization will further aggravate carbon impacts with the expected doubling of global building floor area by 2060 (an addition of over 230 billion sqm of buildings with the consequent increase in demand for steel, concrete, plastics, energy and water).

While some new buildings strive for carbon neutrality, two thirds of the total building stock today will still be around by 2040. Decarbonizing the vast majority of older buildings and the use of less material-intensive construction for new buildings will be among the challenges in addressing climate change and adapting to a warmer world.

The message is clear and simple: to address climate change, we need to change the way we design, build and operate our buildings. This provokes the question, why is our built environment so maladapted and out of sync with our context to begin with? Why is the metropolis so disconnected with the rest of the biosphere?

Self-shading windows and vegetated facade of San Miguel Corporate Headquarters by the Mañosa brothers

Age-old principles

My early years in architecture school exposed me to Tropical Architecture and the principles of passive cooling through the lectures and mimeographed writings of the late Geronimo V. Manahan, a pioneer of urban and regional planning in the Philippines and a beloved mentor. His bioclimatic approach to planning and architecture extended beyond the classroom and were applied to actual prototypes of passively cooled and energy efficient homes. His work followed the principle of “design responsive to place, climate, humanity, culture and technology.”

Transitioning from school and immersing myself in the real world of buildings, I witnessed how the built environment evolved from the brise soleil-clad structures and arcaded outdoor retail environments of an earlier Makati and Ortigas Center to the more hermetically sealed, glass encased and energy consumptive edifices that we see nowadays.

Globalized design, largely influenced by western ethnocentric tastes, has eased out the contextual, pragmatic approaches of earlier decades. And alas, tropical design driven by intuitive local climate awareness, was largely lost in the real world just like those mimeographed handouts of GVM.

But with the pressing need for buildings to respond to the climate crisis, a new focus on these age old principles is needed not only to optimize building performance to the evolving environment, but also to reduce their ecological footprint and improve the health and comfort for their occupants. Ultimately, these principles have to be applied to the scale of buildings, townships and cities.

An older but more climate responsive aesthetic: ledges that

keep the sun and rain out and allow windows to be opened. The

Doña Narcissa building when it still existed, by Gabriel Formoso.—

GF AND PARTNERS

‘Reinserting nature’

The most basic, most intuitive approach to cooling the metropolis while capturing carbon is simply reinserting nature in the urban realm through revegetation and urban afforestation.

Studies by Juanito de la Rosa on urban thermal comfort in Metro Manila demonstrated the dramatic effect of reducing thermal stress through the simple and inexpensive use of planting. Studies by Myrup, Akbari, Oke et al. on urban heat island effects have also suggested a non-linear relationship between area of tree cover and heat reduction, indicating a one-third increase in tree cover can produce two-thirds of the potential cooling due to shading and evapotranspiration.

Research further shows that smaller open spaces that are evenly distributed in a district will have a better cooling effect than having a few large parks. These improvements in outdoor temperature levels can then reduce the energy required to cool the surrounding buildings—the less heat that is absorbed by our paved surfaces and walls during the day, the less heat is radiated back indoors and into the atmosphere at night.

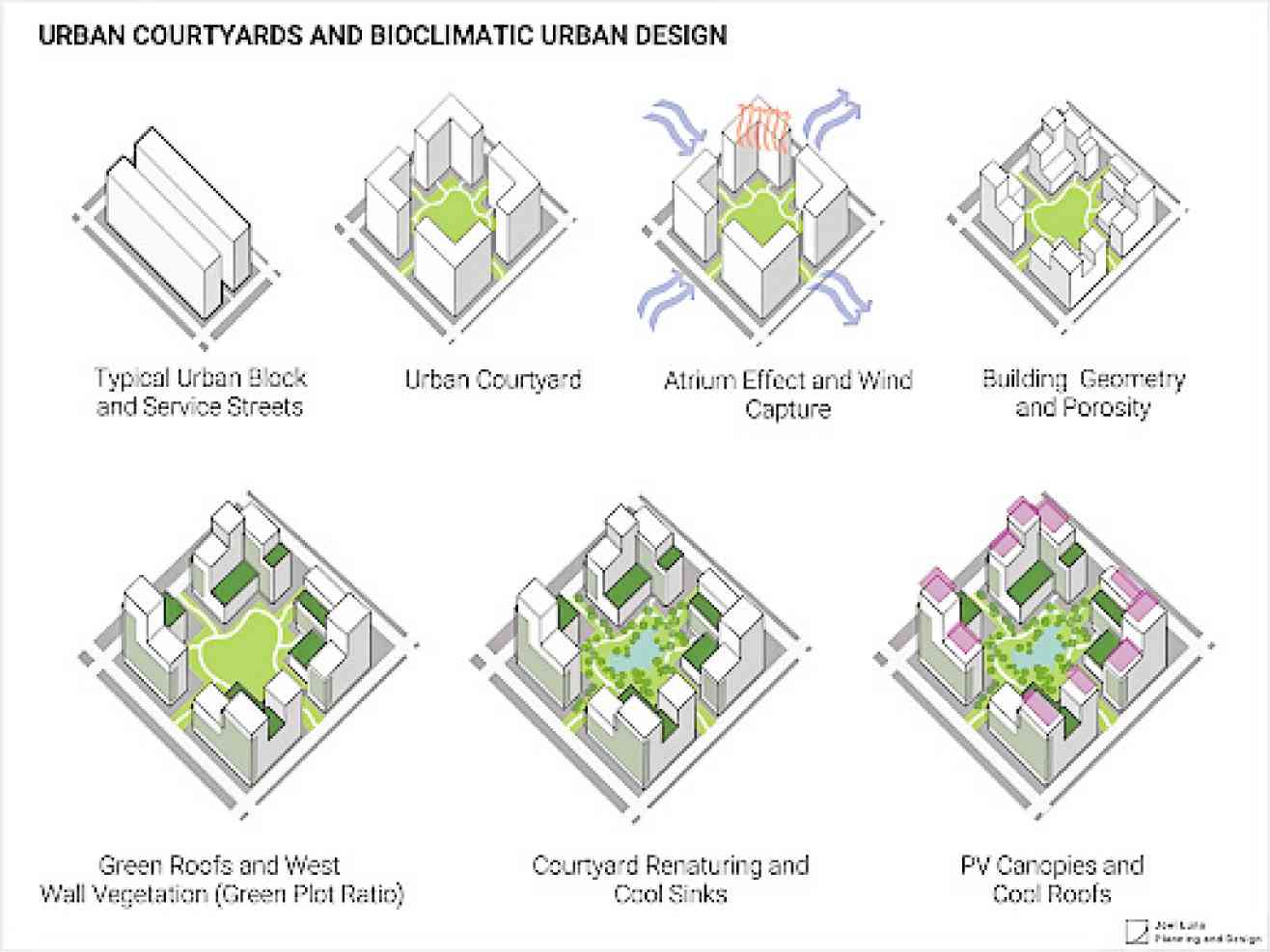

What all these imply is that the energy efficiency of buildings can be increased significantly if the urban blocks that contain them are also designed for energy efficiency.

The grouping and placement of buildings, shading patterns, amount of open space and vegetation and the permeability to air currents create the outdoor microclimate which determine the indoor cooling and energy loads of buildings. Local and at-source interventions can matter significantly.

Cooling our city blocks is a step in cooling our planet.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning and design consultancy firm. www.jlpdstudio.com