The new indigenous architecture

In this era of globalization, countries around the world strive to be known as first-world and progressive.

The concept of modernism often conjures images of glass facades, skyscrapers and steel edifices. Many cities would usually incorporate these elements in their skylines to present an image of a booming metropolis.

With a common goal to appear prosperous, however, cities are beginning to look the same. In many cities across the world, traditional elements are fast disappearing in favor of modern features. Cultural icons are becoming mere historical pieces that were once celebrated but no longer in use.

In the quest to be globally competitive, should indigenous identity take a backseat?

One man from the city of El Alto, Bolivia begs to differ.

Rebelling against the norm

Freddy Mamani, a young builder who comes from a humble background, is making waves for attempting to redefine Andean architecture.

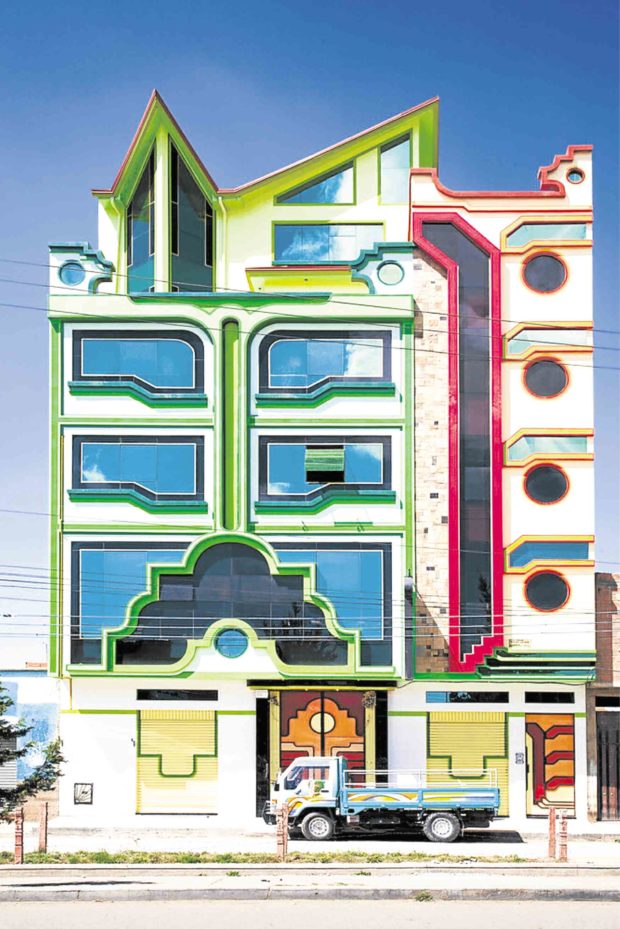

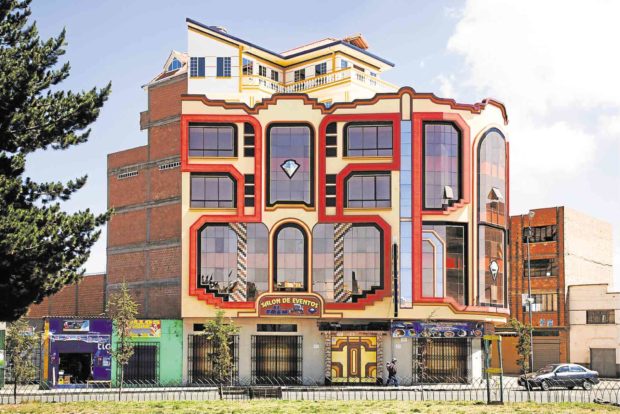

His colorful creations stand out in the sea of customary red brick homes in El Alto, Bolivia. He has become the go-to architect of Aymara rich traders—an emerging elite class of citizens who share his indigenous roots.

It would be difficult to understand Mamani’s success without knowing his country’s recent history.

Bolivia, a landlocked nation in Southern America, has experienced a sudden boom in economy in the past few years. With the election of Aymara President Evo Morales in 2006, the once-weak indigenous communities of Bolivia suddenly had a strong man to support them.

Morales succeeded in pushing the country towards financial independence and economic growth. With the president on his third term this year, the future of Bolivia remains bright.

The City of El Alto, in particular, has seen the rise of wealthy Aymara as they take pride in sharing the president’s ethnicity. By hiring Freddy Mamani to construct buildings inspired by their indigenous culture, the new bourgeoisie are able to tell the world their story.

Since his first commission in 2005, Mamani has built approximately 60 structures to date.

His structures are easy to identify in the dry landscape: wild, vivid forms that are richly colored and lavishly decorated. Most of these buildings stand at 4 to 6 storeys in height. They are usually mixed-use developments that feature grand ballrooms, large common spaces and residential penthouses.

Mamani’s works have been dubbed “cholets” by the Bolivian press, a mix between the word “chalet” and “cholo,” the latter a derogatory term for indigenous people. Critics are quick to point out his lack of formal training and his overt use of decorations.

His works, however, depict symbols, spaces and activities particularly designed for the Aymara. As Mamani states, “In the technical faculty we felt our culture underestimated, but now with President Evo, the original culture is revalued. I have given my design a decomposition and stylization of the Andean forms.”

Modern indigenization?

Whether people liked it or not, Mamani’s work is an attempt to establish cultural identity through built forms. He simply calls his style “Andean architecture,” as it is based on his people’s history, art and customs. His buildings have garnered attention internationally not only because of their bright appearances but also because they seem to match the spirit of their inhabitants.

In this way, he brought the indigenous back to the forefront of design, reviving historical references in the modern age.

Bolivia’s architectural transformation can lead us to ponder how the concept of the “indigenous” can be translated in the Philippine context.

Nowadays, the definition of Filipino architecture is widely debated and assessed. Many people complain that we have lost our identity in our buildings. Mamani’s story, however, reveals an issue that might be preventing us from finding the answer.

The real question is, are Filipinos ready to discover their indigenous roots in the modern age? Mamani’s works were rejected because of their proposed definition of Andean architecture.

In a similar fashion, there is a risk that an attempt to define Filipino architecture might be refused by the Filipinos themselves. At a time when many designers pride themselves in their art, who is actually authorized to create works that define a nation? And if the resulting work is awkward and strange to look at, does this define us as a people?

At the end of the day, whether or not you like Mamani’s work, you can’t deny that the man has guts.

Despite criticisms, he does what he thinks is the best representation of his culture. Likewise, our country needs fearless designers if we wish to define Filipino architecture.

In today’s age of globalization, cultural identity is the best way we can distinguish ourselves from the rest. Though we may face scrutiny and disapproval, any attempt to design Filipino is an effort to tell our people’s story.

By going back to our indigenous roots, we can identify and show off to the world the things we can be proud of as a Filipino.

(Sources: “Andean Architecture of Bolivia”, by Elisabetta Andreoli and Ligia d’Andrea; Photos by Alfredo Zeballos via www.archdaily.com and www.leedor.com; User Moebiusuibeom-en via Wikimedia Commons; www.archdaily.com; www.aljazeera.com; www.curbed.com; www.washingtonpost.com)

The author is a licensed architect who studied abroad and currently works for DSFN Architects. She thinks Filipino architecture cannot be defined by one man’s masterpiece but by many people’s attempts to represent the Filipino culture.