Winning chef celebrates cocoa

She had the audacity to compare cocoa to oil.

I was astounded and boggled before embracing the idea of what this chef was trying to persuade the world to believe.

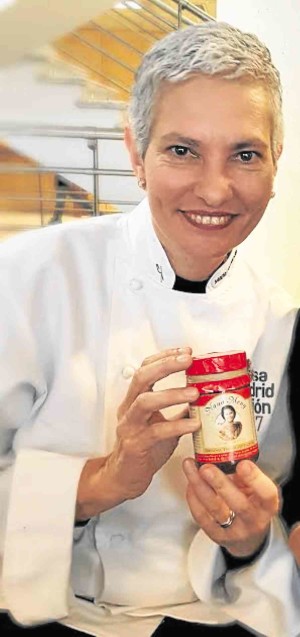

The chef is Maria Fernanda di Giacobbe: A tall, lean, silver-haired lady with a warm smile and a positive energy that glows from within.

Basque Culinary World Prize

She had just been interviewed on the Madrid Fusion stage by no less than chef Joan Roca, whose restaurant El Celler de Can Roca in Girona, Spain had twice already been named The Best Restaurant in the World.

No less than Joan Roca because Di Giacobbe this year became the first winner of the Basque Culinary World Prize.

The award is given to chefs who improve society through gastronomy.

From tragedy to triumph

Di Giacobbe is from Venezuela. Her mother is a famous pastry chef, known for making wedding cakes. Her restaurant, co-owned by her mother, was known for its chocolate cake. She hails from a family of restaurateurs, with her brother, uncles and aunts each having their own restaurants.

In 2004, however, the Venezuelan oil crisis forced them to close down nine restaurants. They were devastated.

But di Giacobbe turned the economic tragedy into a story of success. While in Barcelona, she saw a sign that said “Venezuelan Chocolate” and it hit her: Since cacao is the top agricultural product of Venezuela, they simply had to find a way to sell more cacao.

Cacao is like oil

Today, petroleum exports account for more than 50 percent of Venezuela’s gross domestic product (GDP) and agriculture accounts for a measly 3 percent, with cacao just one of many Venezuelan agricultural products.

So where did di Giacobbe get the wherewithal to dare to push cacao to the status of oil?

From the realization—the truth—that once upon a time, cacao was more valuable than oil in Venezuela.

In fact, cocoa was Venezuela’s most important crop in the 1700s. For centuries, Venezuela was the world’s top producer of cocoa, with European monarchs sipping chocolate creations made from Venezuelan cacao. It was only in the 20th century that the country started to export oil. Today, it is the 6th largest member of the Opec by oil production.

“We have to make something with cacao,” di Giacobbe resolved. “If we take a very typical and traditional fruit,” she theorized, “and make little chocolate balls with local fruits like guava, coconut, pineapple … we can make Venezuelan bonbons (small candies coated in chocolate),” she suggested to her family.

And that’s how Proyekto Bonbon, with the mission to create Venezuelan bonbons, was born.

Di Giacobbe endeavored to study the art of making bonbon chocolate by observing chocolatiers from France, Poland, Belgium and began making Venezuelan bonbons using local fruits and alcohol. It was the kind of bonbon with flavors that will make you remember your grandmother, she notes.

It was such a success, people from different regions in Venezuela started visiting them, asking di Giacobbe to teach them how to make bonbons.

Transmitting knowledge

Soon, the production became big enough to require them to source their own cacao and this, she shares, changed her life.

“You see women with their children dancing and singing to the cacao,” she recalls. “We were in love.”

The love was not unrequited. The women taught di Giacobbe how to plant cacao, and in exchange, she taught them how to make bonbons.

“Now we work together,” she says happily, with the women workers making not only bonbons but a gamut of chocolate products from cocoa butter to cocoa liquor, balls and, yes, bonbons.

She initially taught 10 women how to make bonbons. These ten collectively taught 330 women. The 330 passed the knowledge on further until 700 Venezuelan women were experts at making bonbons. The 700 became 1,500, and now there are thousands of women from various communities all around Venezuela making bonbons.

Eventually, di Giacobbe partnered with the Simon Bolivar University to create a course on cacao industry management. As of today, the course has already seen over 1,500 graduates, 94 percent of whom are women.

Creating the chocolate products, she emphasizes, helped them survive an economy that collapsed. But it was by transmitting the knowledge and helping other women find their own sense of achievement and become “rich in well-being” that she found the most fulfillment.

Taste of heritage

By going back to cocoa as its people struggled to survive, Venezuela has reconnected to its rich heritage.

“We can not only smell the aroma,” she adds, “But you can also taste the geography and (it links you to) the people involved.”

Today, the Venezuelan chocolate bonbon is not only a testament to how a resourceful woman helped her family and community overcome the Petroleum Oil Crisis of 2004, it is also a testament to the strength of the Venezuelan traditions in producing cacao.

Madrid Fusion will once again be in Manila this April 6-8 with the theme “Towards A Sustainable Gastronomic Planet”. For details and updates, visit madridfusionmanila.com.