Narda’s legacy lives on

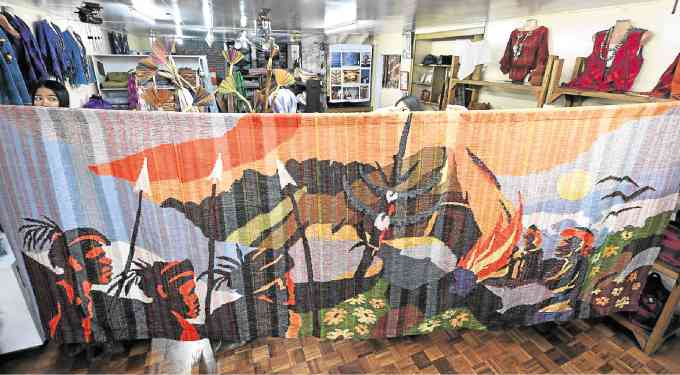

This handwoven wall decor called “Dap-ay (Gathering place)” is one of the largest pieces on display at the Narda’s Handwoven Arts and Craft store on Session Road in Baguio City.

Baguio City—When 28 Miss Universe candidates visited this mountain city last month, Lucia Capuyan-Catanes was busy cataloging handwoven shawls that were gifted to them.

It was one of the many tasks Lucia inherited as the new creative director behind Narda’s, the brand named after her late mother, Leonarda “Narda” Capuyan.

Narda, a former nurse, was the acclaimed Igorot entrepreneur whose “Ikat” (tie-dyed) fabrics drew a huge following in the 1970s. She helped introduce indigenous Cordillera weaving designs to an international market by landing a supply deal in the 1980s with Bloomingdale’s Department Store in New York.

In 2012, her designs and fabrics were showcased in the New York Fashion Week. Three years later, she represented the Philippines in a women entrepreneurs’ exhibit at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) summit hosted by Manila.

Passive observer

Lucia accompanied Narda in the New York event, but she said she was merely a passive observer of her mother’s whirlwind career.

“I was never inclined to take up weaving … . I love cooking,” said Lucia, who established her own pastry shop and restaurant, Ebai’s.

When Narda became ill, she considered passing on the torch to her grandchildren, instead of Lucia and older brother, Bernard. “She thought I was so stubborn,” Lucia said.

Narda died in March last year. A month later, her closest friends approached Lucia and persuaded her to keep the thriving brand of the family-owned Narda’s Handwoven Arts and Crafts.

“My mom’s friend, (former Ambassador to Germany Delia) Albert asked me to write down a summary of what I wanted to do for the company if I took over. And then Habi (the Philippine Textile Council) asked me to spearhead a booth for Narda’s for the September Habi fair,” Lucia said.

“I did not know anything about weaving,” she said, prompting her to immerse herself in the production of natural dyes and to travel abroad “to expose myself to other Asian countries with weaving.”

Nursery level

“There were commonalities like the colors and [weaving] designs, but compared to them, our weaving industry is at the nursery level,” she said.

Lucia was also informed that buyers had been clamoring for fresh products, “so I dug up our old colors and patterns and proceeded to innovate.” During Narda’s prime in the 1980s, the firm had regular buyers from the United States, Japan and Germany.

After a month and half, Narda’s unveiled shawls, ponchos and fabrics made from homegrown cotton colored with natural mahogany, turmeric and cogon dyes.

Sales shot through the roof, Lucia said, convincing her that she could steer the family company.

Demanding chore

Juggling between Narda’s and Ebai’s has become a demanding “morning-after-morning” chore, Lucia said.

“I could not run away from [the businesses] even if I wanted to … . Ideas kept pouring out even when I was reluctant to handle the weaving company… . I want to make [the family’s] Winaca Eco Cultural Village [in Tublay town in Benguet province] a hub for weavers so we can pass on the skills to a young generation,” she said.

“In other countries like Laos and Cambodia, weavers are paid well and respected. Here [in the Cordillera], weaving is something that embarrasses young people who would rather become caregivers abroad, become waitresses,” she said.

“We are trying to bring back weaving as a noble skill, an art, and then—if we can generate more sales—we can raise wages,” Lucia said.

Community weavers

Narda’s was built by community weavers. “Apart from employing weavers, Mama would buy handwoven products produced by women from Kalinga, Abra and Ilocos provinces … . She went around training and working with weavers,” Lucia said.

A weaving school would also ensure that the skills are passed on soon, she said, “because I realized our best weavers have become old.” Narda’s has a staff and work crew numbering 60, but the oldest weavers have served the company for 35 years.

Tapping homegrown cotton produced by Ilocos farmers and spun by the Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) means Narda’s would also help farms being enticed to plant cotton for the garments trade, Lucia said.

“Local cotton is cheaper,” she said, adding that Narda’s is waiting for PTRI to improve a mechanism for “starching” cotton yarn which needs to be stronger for the looms.

Lucia said her parents experimented with silkworm technology but had lost interest when government support for this waned in the 1980s and 1990s.

This was partly due to the government’s inability to bring spinning costs down, she said. Farmers in Paracelis town in Mountain Province are looking into cotton farms because it has a relatively warmer climate than other provinces which suit cotton shrubs.

New direction

Narda’s has retained a high profile because of the new direction and because of a sleek social media campaign that began last October. For example, the firm’s Facebook Page has been introducing the faces behind “Narda’s.” One post discusses “Cordilleran Mother Weavers [who] have the nicest smiles,” such as master weaver, Dolores Bangguigui, from Bauko town in Mountain Province.

But Narda’s remains the core of the company’s rallying pitch.

“We at Narda’s carry on Narda Capuyan’s advocacy. She had always been compassionate with the Cordilleran mothers. As a nurse, she witnessed their ordeals.

“She discovered that they were highly skilled weavers. She founded Narda’s to empower them. She made innovations on the traditional craft that paved the way for the Cordilleran handweaving tradition to the international stage. The legacy of Narda Capuyan lives on!” —WITH A REPORT FROM EV ESPIRITU