Lessons from Titoy Pardo

To say that someone like Jose “Titoy” Pardo has “been there, done that” is an understatement. A well-esteemed entrepreneur, professional, industry captain, civil servant, economic manager, philantrophist, civic leader and family man, he is not the type who withers away. And it’s not just because of the rejuvenating “stem cell” therapy that this septuagenarian candidly admits to using these days.

Most people know him as the chair of the Philippine Stock Exchange and De La Salle University and a former Trade and Finance Secretary—one who has devoted a lifetime giving back to the country. But a long time ago, he was a little boy who lost his father to a plane crash. It was a tragedy that struck when he was only eight, one that forced the young Titoy to mature faster as he became the man of the house, being the only son with three sisters. Losing his father too soon, he admits, was how he likely acquired early on a higher sense of responsibility and the drive towards excellence.

And excel he did, whether as a part of the public or private sector or civil society. After studying at DLSU, he went to the United States and became the first MBA graduate under the Harvard-DLSU Advisory Program (1961-1963). Early in his career, he was among the Ten Outstanding Young Men (TOYM-1972) pool of awardees, gaining recognition in the field of human resource development in his stint at the National Economic Development Authority. More recently, he became a Ten Outstanding Filipino (TOFIL-2011) awardee for business. He has even earned a knighthood from the Holy See—as Papal Knight of St. Sylvester.

As a businessman and franchising proponent, he was one of the original incorporators of Philippine Seven Corp., operator of 7-Eleven which is now the country’s largest convenience store chain. He also brought to local shore fast food chain Wendy’s. Apart from being an economic manager in two regimes (Estrada and Ramos’ time), he was a Commissioner of the Philippine Anti-Crime Commission, a stalwart of Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry and a founding chair of the Philippine Franchise Association, among others.

Pardo has also worked closely with the academe and with a number of foundations and nonprofit organizations. In fact, he got his papal knighthood because he chaired Assumption College San Lorenzo for 12 years. Apart from heading the board of trustees of his alma mater DLSU, he also chairs Assumption Antipolo at present. His work at DLSU and Assumption “keeps his feet on the ground,” Pardo says.

Article continues after this advertisementPeople often wonder and ask him how he has gained access to seemingly all sectors, and this is his reply: “It’s mutual respect and going into situations without any agenda, without any selfish agenda. Just listen and just give your best.”

Article continues after this advertisementHe tries to shy away from the public eye and while he doesn’t want to disappear into oblivion, he tells SundayBiz he knows when it’s “time to bring in new talents and recognize that you need to step aside.” In many of the businesses he had put up, for instance, he was mostly the incubator who later on handed the reins to an able manager, in some cases, his wife. “I was the enterpreneur and I see the forest, but my wife sees the trees and manages them,” he says.

‘Find the need, fill it’

As a young man who had to contend with the untimely demise of his father, Pardo had chosen to be resourceful, taking on summer jobs like delivering PLDT telephone directories or Yellow Pages. He pursued entrepreneurial interest early on, even while he was still in college at DLSU. “I wanted to be independent, self employed, I have that passion for trying,” he says. At one point, he had an automotive repair shop and other service-oriented businesses like airconditioning repair and servicing—with the help of an industrial partner. “I was being drawn both to be a professional and businessman so I divided my work. I was guided by five words “find the need, feel it.”

After college, Pardo applied with a textile company Alpha Textile to run an outlet store of its ready-to-wear brand Jazzie. The top honchos of the textile firm were taken aback when the young Pardo told them that if he would be given only one store to run, forget it. “I said I’ve witnessed families broken by having the wife running a single store on Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, and not being with family because they are glued to their store. I want economies of scale. I want enough stores and I wanted to start with no less than three or four stores.” Thus he was given initially four or five stores and eventually grew a chain of Jazzie stores after that. Running a chain allowed him to hire competent people and not burden all of his family to a single store. This began to open his eyes to the Chinese retailer’s usual formula of opening one store and expanding to as many stores as they had children.

“This brought me to the franchising world—how everything was reduced to a science without the need for excessive controls,” Pardo says, noting this eliminates the need to rely on a child or a relative to jump into the business. From Jazzie, he also acquired a franchise of pizza parlor Shakey’s.

Why is he drawn to retailing? “At the retail end, you’re not as vulnerable to policy changes in government because you’re at the lowest end of the market chain … and you respond to a need and keep yourselves relevant in the marketplace, satisfy customers. That somehow excited me,” he says.

‘During difficult times, manage your cash flow’

Pardo’s business suffered some setback in the 70s when Harrison Plaza, where his start-up Jazzie outlet and also a Shakey’s oulet, burned down. But at that time, there was already a good cash flow from the chain of retail stores.

He continued to look out for other “retail immersion.” One day, he came across an article in Asian Wall Street Journal about Japanese businessman Ito Yukado, who brought the 7-Eleven franchise to Japan in 1973. (The Ito-Yukado group also brought the chain to Hawaii and eventually brought the Dallas-based franchisor 7-Eleven in 1991). Interested in bringing the chain to the Philippines, Pardo traveled to Dallas and presented his case, saying he was “short in capital but long in experience.” At that time, the Alemar’s group of Frank Sibal was likewise applying for a franchise. It was eventually given to them and 7-Eleven became a three-way equal partnership among Pardo, Sibal and the family of Vicente Paterno, Pardo’s brother-in-law who eventually became a Senator.

The group brought 7-Eleven amid a brewing political storm in the Philippines in the 1982-83 period. This was shortly after the assassination of Ninoy Aquino and the conventional wisdom was to bring out capital than invest in the country. “When in doubt, an enterpreneur jumps because we believe in what we’re doing but during difficult times, you manage your cash flow. We didn’t expand rapidly, didn’t borrow money, just worked progressively,” he says.

During the Cory Aquino administration, Paterno joined the government so Pardo managed the initial years of 7-Eleven as well as American hamburger chain Wendy’s which the group also brought to local shore at the same time. When Paterno left government, Pardo swapped roles at the business with Paterno as that was the time that the latter had too many things on his plate. Pardo became president of the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 1992 and then became chair of the board of trustees of DLSU and then Assumption. Paterno, in turn, took over management of 7-Eleven while Mrs. Pardo took over the reins of Wendy’s. Now, Pardo notes that Paterno’s son Victor is doing a “terrific” job as chief executive officer of 7-Eleven, which has become the largest convenience store chain in the country.

‘Not to make easy difficult’

Pardo always has had a soft spot for civil service. “In and out” of government he was, through all these years. During the Marcos regime, he was with the Neda as executive assistant to a few of the council chairs then from Don Filemon Rodqiguez, Alfonso Calalang, Marcelo Balatbat and Placido Mapa—who became his early mentor.

“It was part of my learning curve early in my career to have the vision of looking at the economy through the highest economic policy-making body,” he says. He was afterwards sent to the Asian Productivity Organization (APO), a regional inter-governmental organization based in Japan which the Philippines is part of. “One of the lessons I’ve learned is how effectively one could produce more for less. The fragile resources you have, try to optimize their use so that you can benefit more for less. That’s where the policy perspective of working for the greatest good will evolve from.” It was Pardo’s work on human resource development at APO that earned him, at age 33, a TOYM award—in the same batch as the young Joseph Estrada, whose Cabinet he would join years after.

Pardo says it’s always a puzzle for him why some private individual leaders tend to change when they join government. “Something clouds the minds of businessmen who join government that make them change. So when I joined, I said this is not something I should succumb to. Instead, what I began to do, being both a professional and entrepreneur, because I look at myself as an entrepreneur, I began to see how, the strategy in government is reduction of complexity, not to make the easy difficult. I went with that perspective and then always ready to leave government, not wanting to make myself a permanent fixture.”

He didn’t see himself as a career bureaucrat, adding that all he wanted was “just to make a difference, be able to contribute and be different from the others who join government, wanting to make a career.” He says this is not to put malice to appointees who cling to their posts. “But it has helped me because my advocacies were met with the approval of the President, knowing that I was there not with an agenda to make myself a permanent fixture and I was ready to leave if there were differences in policy perspective.”

During the term of President Ramos, he was recruited to be part of the Presidential Council of Economic Advisers in 1992, and in 1993-1994 was appointed to the Monetary Board, the highest policy-making body of the central bank.

When Estrada, his TOYM batchmate became President, Pardo joined the Cabinet as Trade Secretary. It was the time that the Philippines chaired the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean). “I was active in the international community promoting Philippines and not active in political goings-on,” he says.

Pardo succeeded banker Edgardo Espiritu as Finance Secretary in 1999-2000. He wasn’t the first fiscal manager in the family. His paternal grandfather, Wenceslao Trininad, was actually the country’s first Bureau of Internal Revenue Commissioner in 1932 during the American colonial period. Unfortunately, he never met this lolo, who had passed away early.

Among the reforms undertaken during Pardo’s term was the abolition of the SGS pre-shipment inspection contract and the setting up of a reward and incentives fund that improved revenue collection at the BIR and Bureau of Customs.

Just like the hot debate on the Reproductive Health law, Pardo says in a democracy like in the Philippines, the challenge is always to get a consensus. “You move faster if you’re united. This is where it’s very demanding for leadership to be effective.” As such, his strategy as a leader is to consult all sectors. “But when I enter the room, I would have done my homework,” he says.

‘Deny Status Quo’

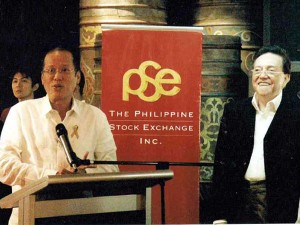

These days, Pardo has no more day-to-day operational responsibilities but is more into policy-making. On a daily basis, he manages time and divides time between private enterprises and nonprofit organizational activities. Obviously, the PSE position is the most demanding of them all as it’s no walk in the park to head the local bourse even at this time that local equities are trading at unprecedented highs. He was the one who had insisted that the PSE lengthen its trading hours to align with regional trends, which was initially met with a lot of skepticism but eventually proven as a good call. It was a “leap of faith,” he says, just like in the early 80s when his group brought in 7-Eleven even if there seemed to be no market for it at that time. “People want status quo but change is the only permanent thing there is. Deny status quo should be your mantra,” he says.

“Integrity and confidence are two virtues that you must have plenty of especially being a self-regulatory organization (SRO) and that’s why I keep on emphasizing that point to our people, trading participants, enjoining all to collectivity. Now that everything appears to be going smoothly in a bullish market, if you want to sustain it, you have to be innovative, have new products,” he says.

Pardo dreams of broadening the PSE’s investor base, from over 500,000 investors (out of close to 100 million in population), the ambition is to bring that up to at least three million. While the PSE is the oldest stock market in the region—about 85 years since the founding of the old Manila Stock Exchange—the bourse still has a thin investor base and much lower number of listed companies compared to regional peers. Apart from making the playing field more conducive to investing, the PSE is looking to develop derivative products and has recently entered into a partnership with Singapore Exchange Ltd. to pursue this endeavor. Pardo is also eager to see exchange traded funds (ETFs) listed on PSE.

Turning 74 this April, Pardo is still very much an active part of business and civil society. In fact, he’s part of an initiative to compile a business legacy series about captains of the local industry, something that his generation wants to leave behind for the younger ones to learn from. “I don’t want to fade away, I just want to be able to share whatever lessons I’ve learned,” he says.