Residential mobility as requisite to economic development

The excitement over increasing mobility as lockdown restrictions are being eased is getting more apparent.

The euphoria is felt as social media platforms feature events, travels, purchases and investments. The impulse to be in motion after two years of impasse translates to the recapturing of markets of businesses which suffered the brunt of the pandemic.

Local tourism is gaining traction as resorts are welcoming more visitors. Buying of properties has transitioned from tentative options to well-grounded decisions. Malls and restaurants are getting crowded as people feel the liberating effect of not having to present vaccine cards. All this affirms that the socio-economic health of a place is a factor of convergence enabled by freedom of movement.

Varying mobility concepts

The concept of mobility and how it relates with development and economic well-being go beyond being able to move from one point to another. There are other forms of mobility that figure in development trajectories, purchasing power and investment decisions. These manifest in the housing, urban design forms and spatial disposition of land uses. Where people choose to settle and the geographical reach of social networks are dependent on the power to reposition from where one is currently located.

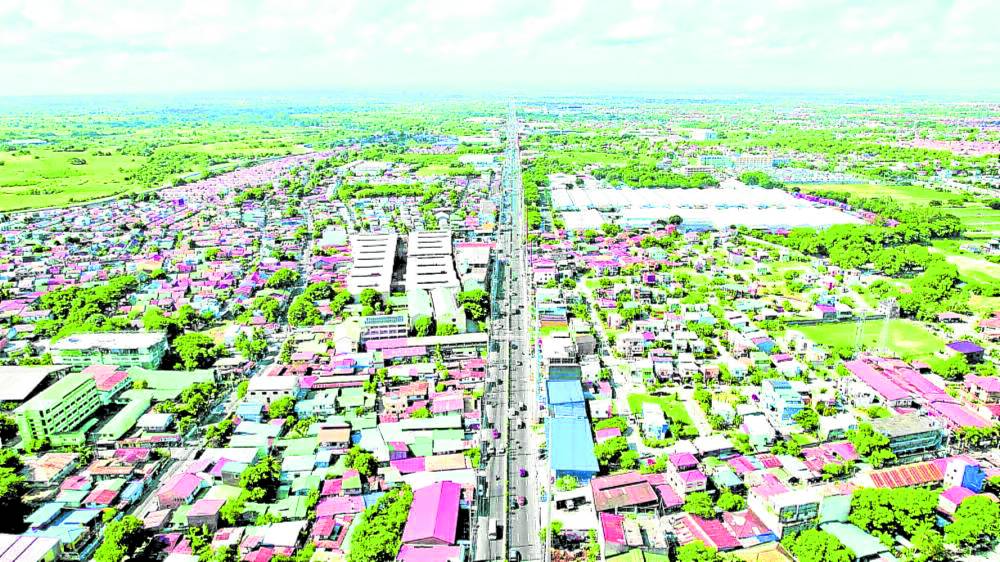

When viewed from the air, dominant housing forms may be correlated with infrastructure and work bases.—karlo king/unsplash

Social mobility, residential location theories

Moving up the social ladder is often perceived in terms of changes in residential circumstances.

Article continues after this advertisementChanges in housing, accommodation and neighborhood typologies would reflect improving life quality that is determined by better access to financial resources.

Article continues after this advertisementResidential location changes have pragmatic and cultural dimensions. Low-income people may opt for shorter home-workplace distance over address and social standing associations, while the upper classes would tend to settle for long distances to be in the socially-recognized addresses.

The filtering theory says that households move to better housing units as their incomes increase and as units are vacated by others who also move up to a higher housing price category (Ta, Chai, 2011). The Tiebout Model or the Voting with One’s Feet Theory accounts for spatial segregation that allows us to demarcate low-income from high-income areas.

This is explained by the willingness of households to pay for their preferred amenities and neighborhood qualities (O’Sullivan. 2007). Dissatisfaction and eventual movement to other places would equate to relocation cost that determines the separate locations of those who can and cannot afford to pay the desired place attributes.

Housing as enablers of labor movement

Moving up the social ladder is often perceived in terms of changes in residential circumstances. —INQUIRER FILE PHOTO

Mobility is essential to economic development because people should be able to move to where their skills are needed (McCann, 2006). Housing should be available where skilled labor and specialized knowledge are needed.

The establishment of business and industry locators in the regions will not guarantee in-migration and relocation from city centers. Housing and amenities form part of the bundle that people consider when deciding to move on a relatively permanent basis. The newly occupied housing stock eventually expands revenue bases due to real estate taxes. New residential bases become new market bases that spur the coming in of new commercial and other revenue-generating activities.

Networking, exchanges of goods and services, flow of information and technology are all basic requisites to progress. All these are facilitated by access, connectivity and multi-directional movement.

Spatial disposition of housing

When viewed from the air, dominant housing forms may be correlated with infrastructure and work bases.

The most expensive houses are concentrated within the inner core of Metro Manila where the cities of Manila and Makati are located, while middle class housing would be in the next ring where the cities of Pasig, San Juan and Quezon City are. The socialized housing units are in the outermost ring that extends to the peripheral urban areas of Antipolo and beyond (Ramos, 2011).

This spatial organization is governed largely by market forces that push low-income housing to where land is available and more affordable.

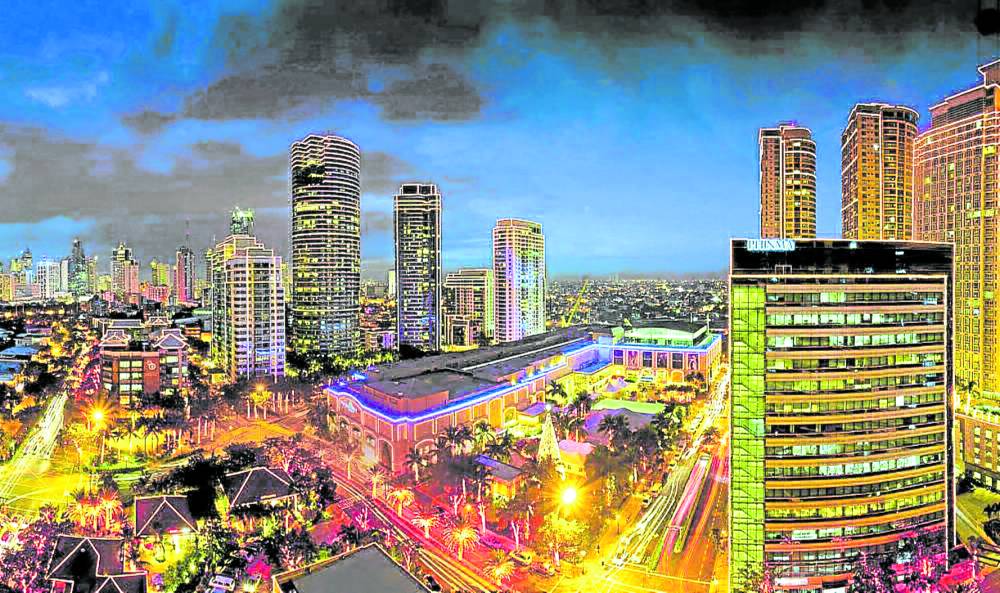

The night satellite view of Metro Manila would reveal where the concentrations of development are as indicated by varying brightness of lights in different places. The less illuminated are the less serviced in terms of infrastructure and community amenities while the most brightly lit areas are the city center locations where the most preferred, and hence most expensive, houses are found.

Where governance comes in

The Urban Development and Housing Act of 1992 was formulated with the underlying goal of tempering market-led house construction and land development. The socialized housing concept is based on cost-subsidy strategies that bring down the cost of public housing. UDHA 1992 is also underlain by the need for pro-active interventions that translate to allocating inner city land areas for socialized housing. The principles behind the provisions of this act would have resulted in the vibrant and synergistic juxtaposition of housing types catering to different markets.

In a democratic setting that is strongly defined by the laissez faire economy, housing location and the consequent collective urban form are governed by prices and competition.

However, not all sectors of society are equipped with the means to take part in this race. Institutions are, therefore, in place to oversee equitable distribution of resources through inclusive funding and land management systems.

References:

Ta Na, Chai Yan-wei, Liu Zhi-lin. (2011). The Origin, Concepts and Research Progress of Filtering Theory Human Geography 2011, Vol. 26. https://rwdl.xisu.edu.cn/EN/abstract/abstract9588.shtml#

O’Sullivan, Arthur.2007. Urban Economics International Edition. McGraw Hill. Singapore.

McCann, Philip. 2006. Urban and Regional Economics. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Ramos, Grace C., Ahn Gun Hyuck. 2010. The Philippine Housing Regulatory System in a Period of Socio-economic Ambivalence. Espasyo: Journal of Philippine Architecture & Allied Arts Vol. 2

Republic Act No. 7279. 1992

The author is a Professor at the University of the Philippines College of Architecture, an architect and urban planner