Misunderstanding the rice crisis

If we misunderstand the rice crisis, we will come up with short-sighted solutions.

There are two major areas of this misunderstanding: the extent of suffering of the rice farmers and the wrong identification of the main cause of our problem.

The farmers are suffering greatly. During a Senate hearing on Sept. 3, it was stated that the P17 per kilo farm gate palay price would give the farmer a P5 profit, assuming a P12 production cost. At four tons a kilo per hectare (which incidentally is not yet achieved by 40 percent of our 2.1 million rice farmers ), his income would be P20,000. The conclusion is that the rice farmer is not suffering today.

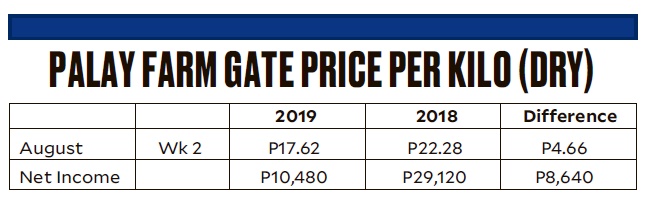

Not true. Even assuming a P12 production cost (which was already P12.42 in 2017), the problem is that at the farm gate, the palay of most farmers is wet, not dry. Most of the farmers therefore get P3 less than the dry palay price, or P14. We constructed the table below from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). We should note that the PSA sampling is from a nonrandom selection, and therefore does not represent the poorer farmers.

Last year, the farmer got a net income three times better than this year: P29,120 versus P10,480. Therefore, if a farmer has only one harvest this year, he gets only P2,427 a month, much lower than the poverty level.

Article continues after this advertisementThe misunderstanding of our rice farmers’ suffering may have caused some government personnel to move sluggishly and, unfortunately, without urgency. Three government agencies tasked to jointly give necessary information to the World Trade Organization to help us with urgent trade measures are behind the written deadline by an alarming five months and 15 days. One government agency is not conforming to the five-day legislated RA8800 deadline, and is behind by 17 days.

Article continues after this advertisementA DA official cannot even trace four official submissions to the department on this critical issue. There is a disappointing lack of DA management systems (less than 10 of 27 DA units have ISO9000). Although only one month in office, Dar has acted impressively by mobilizing governors, other departments, Landbank, the business sector and farmer organizations to help implement his creative initiatives. But he should get better support from the DA bureaucracy.

The second misunderstood issue is that tariffication is the culprit. Thus, there are calls for a return to quantitative restrictions. This would be a disaster.

The problem is not tariffication, but the tariff level at 35 percent.

In the Sept. 3 hearing, Sen. Cynthia Villar said the 35-percent tariff was a WTO commitment she was required to follow. Villar is therefore wisely proposing urgent solutions to address this. The WTO itself and our own law have measures to legitimately increase inappropriately low tariff levels.

One is the agriculture special safeguard measure (SSG). When a trigger high volume of imports is reached, the DA secretary can automatically increase within five days the 35-percent tariff to 47 percent. Despite the Aug. 13 request, this has not yet been done by those who are not giving Secretary Dar the appropriate support.

The other more powerful tool is the general, not special, safeguard measure. But this is not automatic. It requires additional proof, which the DA can easily get, showing that the import surge is damaging the rice industry. This rate can easily exceed 47 percent.

Only last week, the Neda agreed that a rice tariff up to 198 percent can be submitted to the WTO for implementation outside the Asean. This was significantly above a previous study that showed 70 percent as the rate that equated imported with domestic rice. Both are well above the 35-percent rate today.

Why is a higher rate critical? At today’s 35 percent tariff, the landed cost with arrastre and storage is P24 a kilo. With an additional P6 for transport and profit margins, the retailer can sell profitably at P30.

The corresponding price of half of this, from which we subtract P3 for drying, is P12 for the farm gate wet palay price.

If the farm gate price is above P12, the trader would rather get the cheaper imported rice. If the farmer has a production cost of P12.42 and he sells at P12, he will lose and stop planting. This is why we have to increase the 35-percent tariff immediately. This is urgent. Why the delay?

We are fortunate that Sen. Villar, Rep. Enverga and Secretary Dar are leading laudable initiatives to minimize the suffering now. They are looking at this from an industry value chain perspective, with farmers, millers, traders and consumers. We will discuss their significant contributions next week. In addition, we must immediately address the cause, not just the symptoms, of the problem. Avoiding misunderstandings such as the two mentioned here will go a long way in effectively managing our rice crisis.