Department of Water an urgent necessity

Given our water crisis today, a Department of Water must be established at the soonest possible time. Climate Change Commission Secretary Manuel de Guzman argues that, given climate change, this crisis must be addressed immediately. Seventy-three Filipinos die everyday from water-related causes, while we collect only 4 percent of our rainwater compared to India’s 40 percent. The 2014 and 2016 Asia Development Bank (ADB) water studies confirm that a water crisis is not “because of physical, scarcity of water, but because of inadequate or inappropriate water governance.”

In the first of the seven-volume 2017 Philippine water study, Dean Agnes Rola states: “Globally, policymakers, the academe and development practitioners recognize that in order to address issues on water security, an adequate and efficient water governance structure must be in place.”

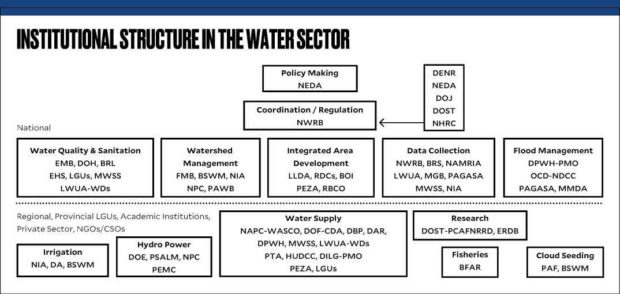

The chart shown here has not escaped the attention of three lawmakers. House Speaker Gloria Arroyo and Representatives Estrellita Suansing and Arthur Yap all echo the urgent need for a Department of Water in bills they separately filed.

Statistics show that our water crisis is getting worse. While our population increased by 51 percent from 70 million in 2000 to 106 million in 2018, our cubic meters decreased by 28 percent from 1,900 to 1,377 per person per day. As the secretary general of a tripartite legislative-executive-private sector steering committee working toward a National Water Roadmap and Summit, I personally saw how difficult it was to implement the key water governance recommendations agreed in the seven water pre-summits held in Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. These were on five subsectors identified in the ADB studies (environment, industry, domestic, urban and resilience) and two sectors identified specifically for the Philippines (governance and agriculture).

Though much has been accomplished through these pre-summits, certain critical recommendations were not implemented because of the current flawed water governance structure. For example, this steering committee unanimously recommended significant budget increases for the critical National Water Resources Board (NWRB), (which does not even have an office in Mindanao or the Visayas), and the River Basin Office, (which supervises the globally approved integrated water resources management approach, but which has an average budget of only P1 million each for its critical 21 water basins). These recommendations were not implemented. For NWRB, the budgets for 2017, 2018 and proposed for 2019 were P129 million, P159 million and P157 million, respectively. For each of the critical river basins, the budgets for the same years were P1.1 million, P1.1 million and P0.9 million, respectively.

Another example of non-responsiveness was the request for farmers to be given the rationale on the balance between the many large irrigation systems (controlled by the National Irrigation Administration) and the comparatively few small irrigation systems (under DA’s Bureau of Soils and Water Management). This would be based on the cost-benefit approach as agreed upon in one of the presummits. This meeting never took place, possibly because these two organizations report to different secretaries. The result is an uncoordinated and suboptimal approach to agriculture water use.