Money costs money

MANILA, Philippines–Is it love or money that makes the world go round? None of us here at the Inquirer is an expert on love, so this will be about money.

On most days, the Inquirer’s business section tries to inform you, the reader, what those in power are doing with your money, where the country’s money is going, and how to make money grow (by telling you how others have done it).

This feature, however, is more of an attempt to respond to the questions you have about those sheets of paper and bits of metal in your pocket, but were too afraid to ask.

It all begins at the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).

Primarily, the institution’s task is to preserve the public’s purchasing power by taming the movement of consumer prices. Most of this happens behind the scenes.

Article continues after this advertisementTo the ordinary citizen, the BSP’s presence is most easily seen in its printing and minting of notes and coins that people use to make a purchase.

Article continues after this advertisementIn a country of over 100 million people, managing the amount of money in people’s hands is no joke.

“The BSP can’t just print as many bank notes or mint as many coins as it wants,” explained Iluminada Sicat, head of the central bank’s Currency Management Sub-Sector.

“What we do is manage the overall cash requirements of the economy,” Sicat said in a recent interview in her office inside the BSP’s Security Plant Complex in Quezon City—possibly the most secure building in the country.

Complex models

Complex models are used, she said, with variables regularly adjusted as data become available, to determine the amount of notes (or bills) and coins in circulation.

These models consider price movements, economic growth forecasts as well as the ebb and flow of different sectors of the economy.

“We translate that into number of notes, coins, and their different denominations,” Sicat said.

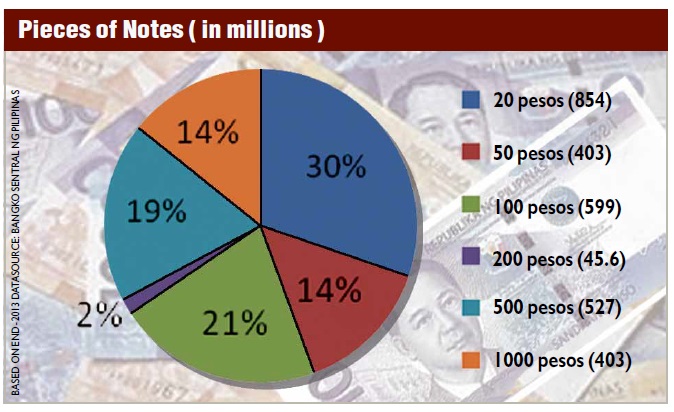

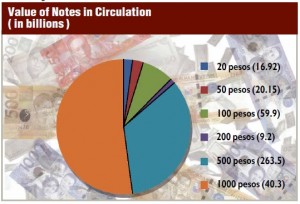

At the end of 2013, there were 2.922 billion peso notes in the economy.

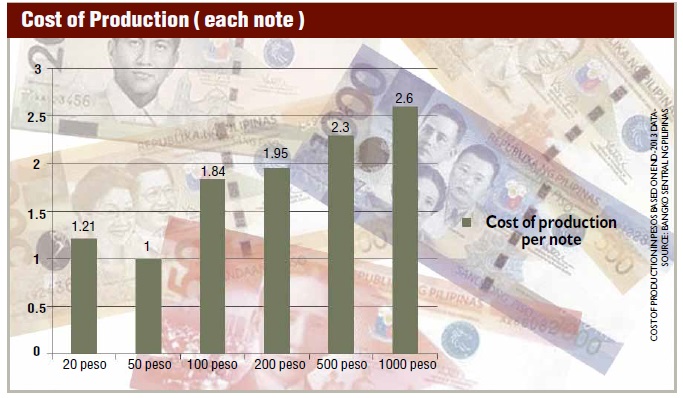

Every year, it costs over P3 billion to print new notes and mint new coins.

The amount of currency printed and minted every year is dictated by the size of the economy and the need to replace notes and coins that are no longer fit for use.

All notes and coins—every peso every Filipino has—are backed up by the BSP’s assets.

This puts a limit to the amount of money that can be let out into the economy.

These assets range from the central bank’s gross international reserves (GIR), which amount to about $80 billion today, to the land that the different BSP buildings around the country stand on.

Next Generation Currency

In 2010, the BSP unveiled its Next Generation Currency (NGC) designs for the country’s notes to replace old designs that were used for decades.

Since late 2010, the BSP has been slowly replacing old bills with NGC notes.

By 2015, the regulator said bills with old designs would be demonetized or would no longer be accepted as legal tender.

The main theme used in the new notes by the BSP’s numismatists—industry speak for people who design money—was popular Philippine tourist destinations.

Under the surface, however, several enhancements were made to make the notes last longer and harder to counterfeit.

For lower denominations like the P20 and P50 bills, which are used by more people, thicker paper was used to make them last longer.

Bills were also treated with anti-bacterial chemicals, again, to make them last longer. Bills, after all, are made using biodegradable materials—20 percent abaca and 80 percent cotton.

“We were designing these during the height of the bird flu scare. And bank notes and coins were said to be carriers,” Sicat said. “So we made the materials more hostile to the growth of bacteria.”

The BSP chose to stick to the 80-20 abaca-cotton mix for the composition of bills due to the bad experience of other countries that tried using plastic-like polymer materials.

Polymers have been used in notes in countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore.

While polymers are indeed more durable, this material does not hold up in certain situations.

For instance, polymer notes should not be crumpled—which simply would not do for wet market vendors and jeepney drivers.

Polymer bills also melt, and the ink fades. “The feedback of other jurisdictions is that their notes lasted a little bit longer but costs doubled. That’s something we have to consider,” Sicat said.

And what happens when notes reach the end of their life?

She said the BSP spends several million pesos a year to dispose of notes that can no longer be used as currency.

Most old notes are shredded and sold to various companies that can use the material as fuel for their furnaces.

Sicat also warned that under current laws, only the BSP is authorized to dispose of bills, which are the central bank’s property.

“What a person owns is the value that the notes and coins represent,” she explained.

THE BSP says the P1,000 bill is themost expensive to produce at P2.60 each because it has the most security features.

New looks for coins

Coins are simpler, Sicat said.

Being made of different kinds of metals, coins are obviously more durable and are cheaper to manage.

This would further reduce the financial strain on the BSP without compromising durability.

“The global trend is to use cheaper metals,” Sicat said, explaining the composition of the P10 coin—the newest kind in circulation—which was made using lighter and more affordable materials.

Piggy bank problem

The biggest issue the BSP deals with in ensuring the adequate supply of coins is the use of “piggy banks.”

In recent years, the BSP through various information campaigns has urged the public to keep using coins.

She said based on the BSP’s data, there were more than enough coins in the country—at over 20 billion pieces—to serve the economy’s needs.

But when coins find their way into piggy banks, coins stop circulating, forcing the BSP to mint more than the economy actually requires.

Based on 2013 data, there were 215 pieces of coins in the Philippines for every Filipino.

India, a much larger population, only has 57 for every person, while Brazil has 104.

“As individuals, we keep our coins in our cars, jars and other containers because that’s part of our savings,” Sicat said.

Making matters worse are charitable institutions that distribute cans to get donations from the public.

Vending machines that take coins are also a problem, she said.

“A significant amount of coins are not circulated,” she said.

The BSP, however, considers getting the coins out of piggy banks and into the economy as just another challenge it has to overcome, as it fulfills its mandate to ensure that the economy’s gears are properly greased, through the circulation of just the right amount of notes and coins.

RELATED STORIES