Mis/disinformation tagged as No.1 threat to global stability

Source: World Economic Forum Global Risks Report 2024: Transitions in the Age of Information

Falsified information is the new major global threat to watch out for.

Miguel Rivera, not his real name, is one of the 30 million Filipinos who gave President Marcos a landslide victory during the highly divisive 2022 elections.

While he did not join any of the campaign rallies because of his age and health, Rivera, 67, nevertheless was able to show his support for then presidential candidate Marcos by defending him online.

He also shared on his social media accounts content that glorified the latter’s father and namesake who was toppled from Malacanang during the 1986 Edsa Revolution.

As the 2025 midterm elections come closer, Rivera is prepared to do it all over again for administration bets.

“They have to win because we don’t want any yellows again,” says Rivera, referring to the color of the Liberal Party, the once prominent administration party that suffered a crushing defeat during the last two national polls.

Some political observers believe that the proliferation of so-called “fake news” partly helped the Marcos heirs make a strong political comeback. Meanwhile, various studies explain how misinformation and disinformation undermine democracy in other countries.

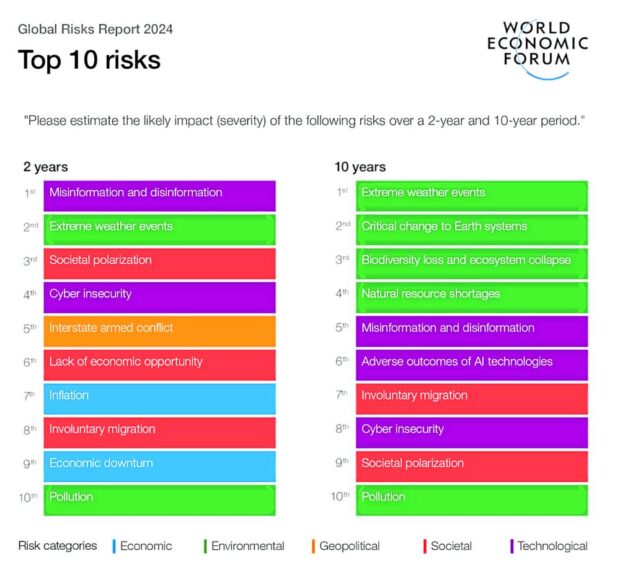

Such dangerous ability to dramatically shape public opinion and divide a nation convinced over 1,400 risk experts, policymakers and industry leaders around the world to rank misinformation and disinformation as the top global risk for the next two years, according to the latest “Global Risks Report” by the Geneva-based World Economic Forum (WEF).

“No longer requiring a niche skill set, easy-to-use interfaces to large-scale artificial intelligence (AI) models have already enabled an explosion in falsified information and so-called ‘synthetic’ content, from sophisticated voice cloning to counterfeit websites,” says WEF.

Political divide

WEF’s report warns of a global risk landscape in which progress in human development is being chipped away slowly, leaving states and individuals vulnerable to new and resurgent risks. Against a backdrop of systemic shifts in global power dynamics, climate, technology and demographics, WEF says global risks are “stretching the world’s adaptive capacity to its limit.”

Based on the report, disinformation is so alarming that it trumped extreme weather events (No. 2), societal polarization (No. 3), cybersecurity (No. 4) and interstate armed conflict (No. 5) in terms of ranking of global risks.

The respondents to the WEF survey also believe that false information will be more dangerous than lack of economic opportunity (No. 6), inflation (No. 7), involuntary migration (No. 8), economic downturn (No. 9) and pollution (No. 10) in the next two years.

WEF also warns countries that are heading to electoral polls soon of a growing distrust of information, as well as media and government sources. This is feared to deepen already polarized views and start a vicious cycle that could trigger civil unrest and “possibly confrontation.”

“Foreign and domestic actors alike will leverage misinformation and disinformation to further widen societal and political divides,” says WEF.

“The widespread use of misinformation and disinformation, and tools to disseminate it, may undermine the legitimacy of newly elected governments. Resulting unrest could range from violent protests and hate crimes to civil confrontation and terrorism,” it adds.

Apart from its threats to democracy, disinformation could also be damaging to global trade and financial markets depending on the systemic importance of the affected economy, WEF explains.

“State-backed campaigns could deteriorate interstate relations, by way of strengthened sanctions regimes, cyberoffense operations with related spillover risks and detention of individuals (including targeting primarily based on nationality, ethnicity and religion),” says WEF.

Harder to track

According to WEF, recent technological advances have enhanced the volume, reach and efficacy of falsified information, making disinformation “more difficult to track, attribute and control.”Disinformation has also become “increasingly personalized to its recipients and targeted to specific groups,” the report notes.

But WEF says governments are beginning to roll out new and evolving regulations to curb disinformation from its source, and AI may complement these efforts. For example, China requires creators of AI-generated content to put a watermark to prevent unintentional misinformation through AI hallucinated content.

For Anthony Lawrence Borja, political science professor at De La Salle University in Manila, the danger of disinformation on the upcoming Philippine elections next year “lies with old pernicious principles of propaganda being aligned with technology that, in turn, is harnessed through organization like new forms of troll farming.”

“It depends on whether organizational techniques are aligned with both emerging information and communication technologies, including artificial intelligence, as well as the shared values and prejudices of a target market,” says Borja.

“It becomes a matter of fueling pre-existing psychological tendencies through more sophisticated spectacles of manipulated and manipulating information,” he adds.