Death and taxes

It’s been said time and again that nothing is certain but death and taxes. This certainty of having to pay taxes even after death was codified and incorporated into Philippine law in 1916.

Act 2601 which took effect on July 1, 1916 was the first inheritance tax law of the Philippines. It imposed graduated rates computed on net inventoried property left by the deceased.

Subsequently, the provisions of this Act were embodied in Section 1536 of the Revised Administrative Code which imposed a tax upon every transmission by virtue of inheritance, devise, bequest, gift mortis causa, or advance in anticipation of inheritance, devise or bequest.

Since then there have been various laws and issuances amending the estate taxes and rules applicable.

Considering that the estate tax that is applicable is that which is in force at the time of death of the deceased, what would be relevant to most are the tax codes of 1997 and its substantial amendment which came in 2017.

Republic Act 8424 is the National Internal Revenue Code of 1997 (Tax Code of 1997) which provides that the estate tax is to be imposed on the net estate of the deceased which also includes the transfer of the decedent’s estate to his lawful heirs and beneficiaries based on the fair market value or the zonal value of real property whichever is higher at the time of death. It is a tax on the privilege to transmit assets and property upon death. (Section 85)

The Tax Code of 1997 was amended in 2017 by Republic Act No. 10963 which is commonly known as the TRAIN Law. This amendment took effect starting January 1, 2018. The TRAIN Law amended several provisions of the Tax Code of 1997 including the provisions on Estate Taxes.

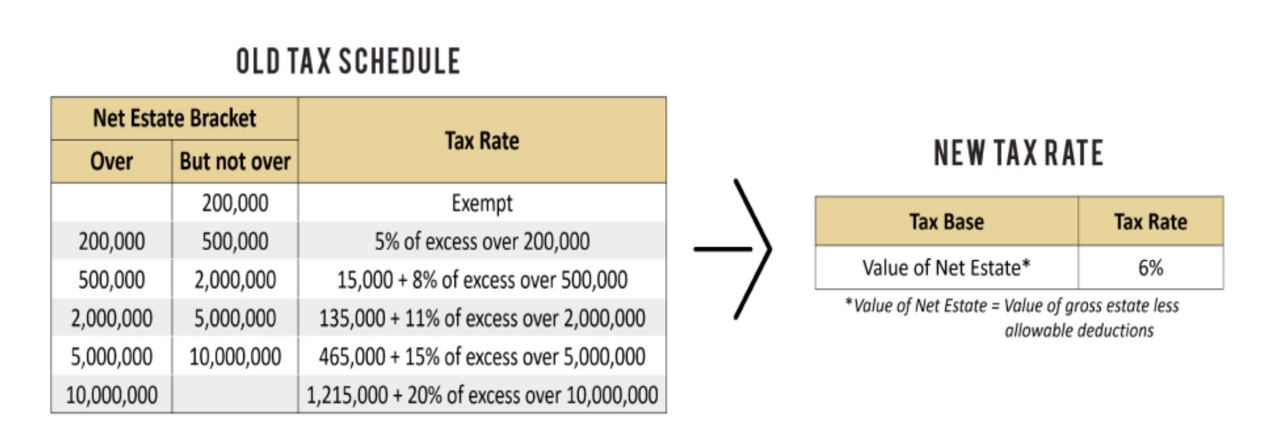

The first major change was the rate of the tax from a graduated rate to a fixed rate.

Under the Tax Code of 1997, the estate tax to be paid by the estate of the deceased was computed based the net estate of the deceased based on a table of rates consisting of six brackets where the rates would range from 5 percent to 20 percent. Accordingly, the following estate taxes were in effect for the period of Jan. 1, 1998 up to Dec. 31, 2017.

The TRAIN Law changed the rate starting January 1, 2018 from the graduated rate in the table above to a single flat rate of 6 percent still based on the value of the Net Estate — which is the Gross Estate less the Allowable Deductions.

Other notable changes from the TRAIN Law relate to the Computation of the Net Estate & Deductions and Administrative Procedures.

In the matter of Computation of the Net Estate, the following are some notable points.

a. Deductions from the gross estate pertaining to actual funeral expenses or 5 percent of the gross estate, judicial expenses and medical expenses were removed

b. The amount of standard deduction was increased from P1 million to P5 million

c. Allowable deduction of the Family Home was increased from up to P1 million to a maximum of P10 million. The requirement of submitting a certification from the barangay captain of the locality has also been removed

d. Standard deduction amounting to P500,000 is now allowed but deductions for non-resident estates relating to losses, debt, expenses and taxes have been removed

e. The requirement to include in the estate tax return that part of the non-resident alien’s gross estate properties and assets not in the Philippines to be able to claim deductions has been removed

f. The threshold level for the gross value of the estate was increased from P2 million to P5 million in cases where the submission of a statement certified by a certified public accountant is required

While the above changes are significant in the sense that it rationalized the rate of the estate taxes and provided for more deductions that are more in keeping with the times, there are other equally significant changes brought by the TRAIN Law which relate to the procedural or administrative aspect of estate taxes.

Previously, when a person dies, their administrator, executor, or heirs must file a notice of death with the BIR within two months. In addition to that, the estate tax return and payment would have to be filed and paid within six months from death. Now, there is no more requirement of filing a notice of death, and the time to settle the filing of the return and payment has been extended to one year from the date of death, which is extendible by 30 days.

In the event that the estate has insufficient cash to pay for the estate tax and more time than the one year period would be needed to raise the funds from the assets of the deceased, the law also allows for payment of the estate taxes on installment basis for a period of two years, if the estate is settled extrajudicially, and not more than five years, if the estate is settled judicially, without penalty and interest. (Section 26, TRAIN Law and Revenue Regulations [RR] No. 12-2018, as amended by RR No. 8-2019)

It is also significant to mention that the TRAIN Law allowed the removal of the P20,000 withdrawal limit of money from the deceased’s bank account. Prior to the TRAIN Law, withdrawal in excess of the amount was allowed only upon submission of a certification issued by the BIR. At present, withdrawal of money from the deceased’s bank account may be made without limit for as long as a 6-percent tax is withheld by the bank and remitted to the BIR.

These changes are important in that it is expected that they would have the effect of spurring greater tax compliance as it makes the reporting, filing and settlement of the estate tax easier. It is believed that the lowering of the estate tax rate to 6 percent which is the same as the capital gains tax on transfers of property, removes the temptation from the taxpayer to make fictitious sales in preparation of death. The increases in deductions have also allowed the law to keep up with the times. The administrative and procedural changes such as doing away with the notice of death, extending the time to file the return and pay the estate taxes, allowing for an extension of payment on installments, and allowing the withdrawal of money from the deceased’s bank accounts immediately, are all good and practical changes that make compliance easier especially for the heirs and loved ones of one who has passed away, as they are expectedly still dealing with and grieving the loss of their loved ones.

Because of these changes, it would be reasonable to expect a higher degree of tax compliance and settlement of estates.

In closing, it is essential to point out that the Estate Tax Amnesty has been extended from the original deadline of June 14, 2021 to June 14, 2023. Accordingly, for estates of those who died on or before Dec. 31, 2017 and which have validly availed of the amnesty, the estate tax due would be 6 percent of the net estate without penalties. (Republic Act No. 11213, RR No. 6-2019, Republic Act No. 11569, and RR No. 17-2021)

(The author, Atty. John Philip C. Siao, is a practicing lawyer and Co-Managing Partner of Tiongco Siao Bello & Associates Law Offices, a Professor at the MLQU School of Law, and an Arbitrator of the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission of the Philippines. He may be contacted at jcs@tiongcosiaobellolaw.com. The views expressed in this article belong to the author alone.)