Sexist in the city

Many things in society persist by inertia—cultural norms, traditions, ways of thinking.

In some ways, these help preserve culture, values and institutions. But many also tend to entrench outdated thinking. Most insidious among these are flawed views and biases, carried over from less enlightened times and now imbedded in our way of life and even in our built environment.

Take for instance gender inequity in our cities. Not many are conscious of how unequal our society has shaped urban forms, to the disadvantage of half of our populace.

Ask any woman if they are comfortable walking the streets or commuting via public transportation alone at night, and you will see how unfriendly our cities are to women.

Male dominance

Architecture is rife with symbolism that reflect male dominance. Skyscrapers, towers and monuments commemorate conquests and represent the male anatomy. Symbols of power such as highways and fast cars celebrate the male ego.

Article continues after this advertisementThe view that built forms are masculine and nature is feminine is an ancient stereotype. This binary thinking fueled the dominance of men in the planning and design professions and has carved inequity in urban accessibility for women.

Article continues after this advertisementGendered urbanism can also be less direct. Filipino women have a better education profile than men, yet they are underrepresented in the labor force.

Urban patterns

Vulnerability of females to disaster are higher than males especially when they are in a lower socio economic group.—AFP

Why is this? While gender roles in home production and childcare are probably one of the main barriers for economic access and opportunities, the imbalance is reinforced by urban pattern.

Many elements of cities reflect vestiges of patriarchal norms and gender stereotypes that have associated women to domestic spaces, excluding them in the considerations of mobility, security and economic production.

Single-use zoning and suburbanization have denied equal economic opportunity for women by bringing homes farther from jobs and limiting mobility options in the suburbs. Whether by walking, cycling, driving or commuting, there are attitudinal differences in mobility between men and women, revolving around the perception of risk.

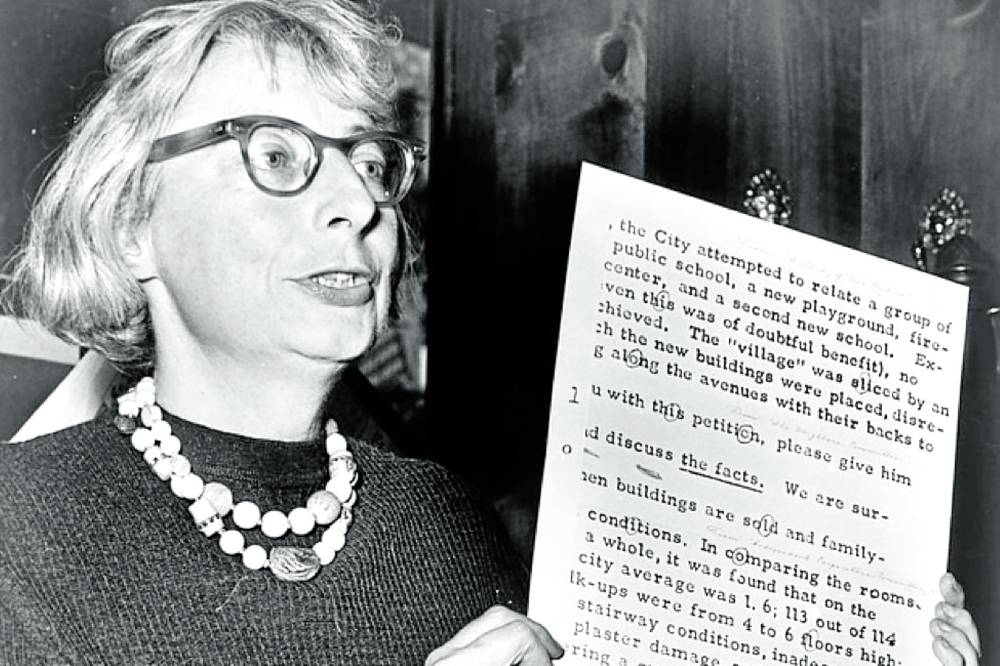

And yet, many transformative events were initiated by women: Black Lives Matter was founded by black women; Habitat for Humanity was co-founded by a woman; the Community Pantry in the Philippines was spearheaded by a woman, Patricia Non. And of course, it was Jane Jacobs who opened everyone’s eyes to people-centric urbanism, standing up against the authoritarian and power-seeking methods of Robert Moses, who dominated the planning of New York for four decades and shaped it according to his whim.

We asked some women steeped in shaping the built environment how they feel our cities can be more equitable for women. Their insights underscore a need for a broader form of inclusive urbanism.

Mari Arias — Architect and Urban Designer

The first step to creating more inclusive cities is to involve its stakeholders in the planning process—to better understand people’s needs and how urban spaces are being used. A more participative approach in planning and design ensures all genders, especially women and minorities, will have a say as to how spaces should be designed in order to foster safe, accessible, gender-inclusive and gender-sensitive cities.

Mea Dalumpines — Architect and Placemaker

Focusing on the pedestrian’s needs at the onset will ultimately produce safe and welcoming places not just for women and the LGBTQ community but also for seniors, children and persons with disabilities. Focusing on safety (lighting), social interaction (wide spaces and seating), mobility (transit nodes that accommodate commuting mothers) and privacy to allow marginalized sectors to freely express themselves is key.

Also, it’s imperative to engage and include women and members of the LGBTQ in the design and decision-making processes. It encourages accountability and empowers them in their rights to the city, from gender-inclusive housing, public spaces and transport systems. Representation of key women and queer personalities in history is also important in signaling gender-inclusion and in diminishing public hostility towards marginalized sectors of the community.

Cherie Fernandez — President, COO of SharePro Inc.

(Filinvest Planning & Implementation Co.) Building cities starts with a vision and making a great city should advocate inclusiveness. A sound framework needs to include a conscious participation of women in planning, governance and implementation. Seeing women in action, valuing their inputs and acknowledging their contributions will establish equality in the urban development landscape.

Bea Dolores — Advocate for heritage and mobility

Women’s safety should be considered in planning, so we can avoid opportunities for street harassment—like designs wherein a female pedestrian can be cornered, or cannot escape from their abuser. Better walkability, like shorter walking distances and evenly paved sidewalks, is thoughtful for women wearing heels.

Gloria Teodoro — Dean of the School of Architecture (Mapua University)

Cities can be made more inclusive to all genders, especially women, if they were engaged in all phases of the planning process. This would ensure that women’s perspectives were considered in locational decisions, in policies that would affect how they navigate the city, their sense of security, health and well-being. This would translate to urban spaces that are not only gender inclusive, but more nurturing to children and protective of the elderly, sectors whose care most women take an active role with.

Broadening the perspective

We need planning that is without the hubris of masculinity. Gender is a social construct and our social constructs shape our cities.

A feminine eye will broaden the perspective and see the gaps we have created in our gender-insensitive environments. In shaping better cities, perhaps the best mind for the job is a woman’s.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning consultancy practice (www.jlpdstudio.com)