Supporting front-liners in the war against pollution

So what did a marine scientist and an explorer find when they descended into the Emden Deep in the Philippine trench? Nope, there were no ancient sea monsters or undiscovered fossils of dinosaurs. But they found trash. A lot of trash.

Located in the Philippine trench with a depth of about 10,400 meters, Emden Deep is a unique marine feature east of Mindanao. Yet Filipino oceanographer Deo Florence Onda and American explorer Victor Vescovo found that they were not alone in the third deepest point in the world during their mission on March 23, 2021.

Fellow “travelers” already started their descent ahead of them: plastic bags and packaging, stuffed toys and even clothes. What was even more surprising was that the plastic materials were still intact. Vescovo saw that these things did not degrade even if they were in the deep parts of the ocean.

It remains unclear how such human debris reached Emden Deep. Onda says that with ocean currents, some of it could have come from other Pacific Islands, or from coastal communities near the Philippine trench.

This comes as no surprise as much of the planet is already drowning in discarded plastic. It is, without a doubt, a pressing environmental issue that requires humanity’s utmost attention. In a recent report by the National Geographic, “plastic pollution is most visible in developing Asian and African nations, where garbage collection systems are often inefficient or nonexistent.”

A 2021 report from the World Bank has said that plastic plays a vital role in the lives of poor and middle-income families in the Philippines as it provides low-cost consumer goods to this segment through sachets, or the “tingi” culture.

But the “sachet economy” contributes to the worsening problem of marine plastic pollution. The World Bank estimates that the Philippines consumes 163 million pieces of sachets every day.

In a global scale, according to the pioneering analyses of plastics, the world’s scientists calculated that humanity has produced 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic, 75 percent or 6.3 billion MT of which became plastic waste. Along with discarded metal, rubber, paper and glass, the vast majority of plastic waste materials lie in landfills or float silently in our rivers, lakes and oceans.

There’s so much plastic lying around that scientists are proposing this era to officially be termed the Anthropocene, an epoch completely dominated by humans marked on the fossil record not by fossilized bones, but plastic.

Circular economy

In order to address the mismanagement of plastic waste, the World Bank proposes that the Philippines must transition into a circular economy. It says the country should pivot toward a plastic value chain approach to evaluate its plastics recycling industry and its role in supporting a circular economy. It identifies major challenges, market drivers and opportunities for scaling up recycling efforts via targeted public and private sector interventions.

Instead of discarding recyclable plastic products, it says these should be upcycled into valuable materials.

Regional organizations such as the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (Pemsea), is pushing for an integrated solution to coastal and marine problems, including marine plastic pollution. They seek out Pinoy waste pickers and junk shops to help turn the tide of the insufficient solid waste management in their own way.

“To decisively address plastic waste management, we need to include waste pickers and recyclers as major stakeholders,” says Aimee Gonzales, executive director of Pemsea.

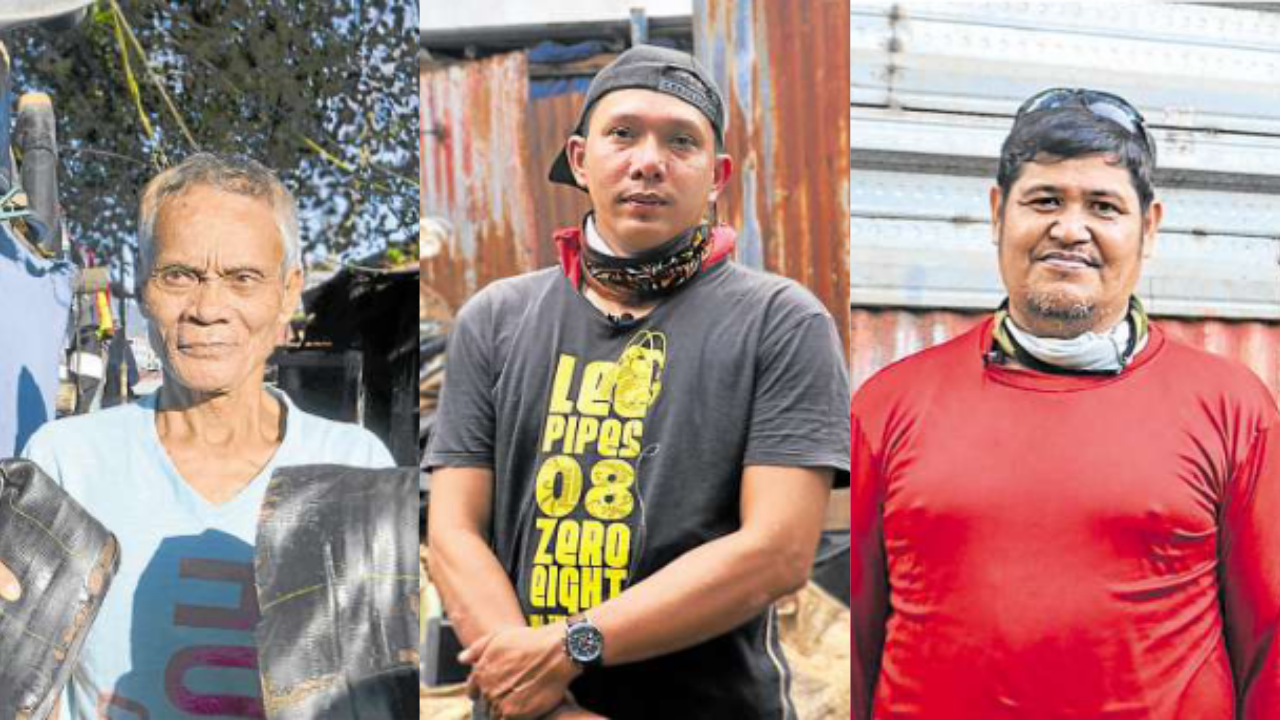

Sherwin Salazar, a 38-year-old mangangalakal or waste picker, considers a junk shop in Dasmariñas, Cavite, as his office. It has been his main source of income since he was 12.

While other kids dreamed of the latest toys or video games, Sherwin “hunted for treasure” in Cavite’s garbage dumps. “I was still in school when I started pawing through old lots, dumps and river banks in a never-ending search for bakal, bote, plastik at dyaryo (scrap metal, bottles, plastic and newspapers). I used a big old sack that weighed so much,” he recalls.

“Since I worked hard, I was taken in by a junk shop, where I earned around P100 daily,” he adds.

From using a brawny sack to collect his “treasures,” Sherwin now owns a motorized tricycle, which brings him to nearby cities like Tagaytay. “Most Filipinos think pangangalakal is nothing more than a dirty job, but it’s far better than working in other jobs like construction. You become your own boss and control your time so if you put in the hours and effort, you can make a surprising amount of money. These days, I make anything from P1,000 to P1,500 daily. Yesterday I made P1,200, even more than a call center agent,” he says.

By exploring the garbage of others, Sherwin was able to provide for his family and send his children to school. “The life of a waste picker is definitely dirty, but if you meet life’s challenges head-on and ask for a little help from above, then it’s really rewarding,” he says.

Enabling recycling

On the other hand, Arles Gozar is turning trash into cash. Arles runs the Angela Mae junk shop in Dasmariñas, Cavite. He employs nine to 15 part-timers to help pick and pack garbage that waste pickers bring to junk shops.

“Many people in this area don’t have jobs. By employing people even part-time, my tiny junk shop helps provide for them and their families. The garbage of others provides a good life for our family—I can even help my relatives from the province when they’re down and out, because we have a little extra,” he says.

Every few minutes, a new picker brings in choice pickings in exchange for cash. Most valuable of all is tanso or copper, sold at P355 per kilogram, followed by sibak or hard plastic (P15/kg), bakal or scrap metal (P14/kg), yero or corrugated iron sheets (P11/kg), bote or plastic bottles (P10/kg), lata or tin cans (P8/kg) and karton or cardboard (P4/kg).

Junk shops like Arles’ provide a vital solution in the world’s quest to minimize waste—by recycling, upcycling or otherwise making use of items, which would otherwise be bound for landfills and dumpsites. Less trash means less garbage flowing down rivers whenever a dumpsite floods.

Junk shops are thus part of the solution to pollution. “We’re of course business owners first, but in our own small way, we’re doing what we can to help keep our country clean,” says Arles.

While reducing waste, recycling provides livelihood opportunities to some of the world’s poorest communities.

Miguel Sabaño, 57, once relied on nearby brackish-water fishponds for food and livelihood. This changed when some of Cavite’s fishponds were converted into offshore gambling centers. Miguel and many others found themselves unemployed. “Now all we have are these scrap rubber tires,” he says.

Making use of their time when no better jobs like construction arise, Miguel and the residents of his community while away the hours ripping out endless rows of polyester or nylon threads, which give motorcycle tires and inner tubes their pliable structure. They use an array of tools—rusty pliers, converted nail cutters, even their bare hands to tear and pluck off threads, which form tiny piles by their feet.

Once cleaned, the tubes and tires sell for P20/kg, enough for about half a kilogram of rice. A long day’s work might yield two kilograms of processed rubber. “It’s not a lot, but having rice today spells the difference between life and death for some people,” he says,

Being large and durable, rubber tires take anywhere from 50 to 100 years to decompose naturally. Instead of being dumped into landfills, they can be shredded and turned into chips, powder, cement or fuel. Used tires can also be turned into tables, chairs, garbage bins, plant pots, sandals and other useful products, providing further income for communities which can find creative uses for them.

Sherwin, Arles and Miguel all play a key role in combating waste. They are considered front-liners in the environmental battle against plastic pollution. Waste pickers, recyclers and junk shops may be among the dirtiest jobs in the world but they play a major role in sustainability.

Sustainability advocate

“Supporting waste pickers and recycling facilities converts a significant portion of waste, which would otherwise be dumped in landfills or in our rivers and seas, into useful products. These cottage industries also support the lives and livelihoods of thousands of Filipinos,” explains Thomas Bell, who manages Pemsea’s Project Aseano.

Project Aseano aims to develop and promote sound and sustainable measures to reduce the impacts of plastic pollution and their implications on socioeconomic development and the environment. The project focuses on the city or municipal level, with Cavite’s Imus River as one of two project sites.

According to the Environmental Management Bureau, Cavite generated an average of 1,514 tons of waste daily in 2018, 22 percent or 333 tons of which could still be recycled. The Imus River traverses the highest waste-generating cities in Cavite—Bacoor, Dasmariñas and Imus, making it a conveyor belt for plastics flowing out to Manila Bay.

Funded by the Norwegian Development Program to Combat Marine Litter and Microplastics, Aseano is led by the Norwegian Institute for Water Research and the Center for Southeast Asian Studies Indonesia in close collaboration with the Pemsea Resource Facility and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) Secretariat under the purview of the endorsing Asean sectoral body, the Asean Working Group on Coastal and Marine Environment.

The results of the project will be synthesized into a local government training manual, tool kit and best practices handbook of policy, monitoring tools and technologies for plastics management that can be used as a reference by local governments in Cavite, the rest of the Philippines, plus the entire Asean region.