Retracing Rizal’s steps

Filipinos continue to honor the life and works of Dr. Jose P. Rizal, whose words had outlasted his own life, influencing many generations following his death in 1896.

As we commemorate the 158th birth anniversary of our national hero on June 19, let us also recall the significant structures and locations where Rizal was born, had studied, was exiled, and imprisoned before he met his demise in the hands of a firing squad.

Calamba

Born to an affluent family, Rizal grew up in what was said to be the first stone house in Calamba.

The Mercados were among the richest tenants of the Calamba hacienda—the first to own a piano, keep stables and a carriage, and to have a home library.

The house where Rizal grew up had two floors and a red tile roof. The ground floor was made of stone, while the upper floor was made of hardwood structure with ipil paneling and narra floors. The front door opened into the indoor driveway that led to a big orchard behind the house. Various fruit trees like atis, santol, tampoy, makopa, plum and balimbing—which Rizal frequently mentioned in his writings —were planted here.

On one side of the driveway was the grand stairway that led to the sala upstairs. Rizal’s home had a spacious parlor with wide capiz shell windows and a pantry leading out to a balcony overlooking the orchard. The house also had two dining rooms, one for daily use and one used for banquets. Located on the ground floor meanwhile were the servants’ quarters, a work room where cocoa and coffee beans were grounded, an oven where bread was baked and a store room for food supplies.

A part of the house was open to the street for the shops kept by Rizal’s mother, Doña Teodora. These included a flour mill, a dye factory, a drugstore and a bazaar. A small nipa hut meanwhile served as the young Jose’s hideaway.

Unfortunately, because of a land dispute with the Dominican friars, Rizal’s family was evicted from their home in 1890 and the house soon after fell into disrepair and was demolished. The present structure was reconstructed in 1950 by National Artist Juan F. Nakpil from funds donated by school children.

Madrid

After completing his medical studies at the University of Santo Tomas, Rizal left the Philippines on May 3, 1882, and arrived in Madrid in September the same year.

Rizal then enrolled in a course in medicine at the Universidad Central, after which he also took up philosophy and letters. He likewise took lessons in painting and sculpture at the Academia de San Fernando; lessons in French, English and German at Madrid Ateneo; and fencing at the schools of Sanz and Carbonell.

Today, we see tangible reminders of Rizal’s stay in Madrid including a replica of the Luneta monument in Manila, which stands proudly at the junction of Avenida de las Islas Filipinas and Calle Santander. Built in 1996, the monument is a venue for the Commemoration of the Birth Anniversary of Rizal every June 19 and the Rizal Day Celebration in December 30, participated in by the Filipino community in Madrid, the Knights of Rizal-Madrid Chapter, and Philippine embassy officials.

Rizal’s Madrid—a walking tour of places associated with Rizal—begins at Calle Amor de Dios 13-15, where Rizal stayed from Sept. 12, 1882 to May 1883. Here, Rizal lived with Vicente Gonzalez, an old friend from his Ateneo de Manila days and a guy whom he fondly called as Marques de Pagong.

The house could have been chosen out of convenience since it was near the university and the atelier in which Rizal’s interest in the arts developed into fine form. There was a piano and four big mirrors that created lasting impressions on Rizal.

Also included in the itinerary of Rizal’s Madrid Walking Tour were Las Cortes Españolas, where Rizal and his friends lobbied for Philippine rights; Ateneo de Madrid, where he studied English, did research work and watched theater plays; Facultad de Medicina de San Carlos, where he finished his course in medicine in 1884; Calle Atocha, where “La Solidaridad” was published; Viva Madrid, Rizal’s hangout and the place where he took most of his meals; Los Gabrieles, a bar frequented by the Philippine Propaganda Movement in 1882; Calle Manuel Fernández Gonzáles, 8, which was Rizal’s second residence; Hotel Inglés, where Rizal gave a speech urging the Filipino youth to follow in the footsteps of Luna and Hidalgo; Ventura de la Vega, 15, which housed the Circulo Hispano, an association of Filipino students and Spanish sympathizers; and Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, where Luna, Hidalgo and Rizal studied Fine Arts.

Dapitan

In July 1892, Rizal was exiled without trial to Dapitan, Mindanao for allegedly instigating sedition. He was made to stay in the house of Capt. Ricardo Carnicero, commandant of Dapitan, in Casa Grande. A friendship based on mutual respect developed between the two gentlemen.

After a year living in Casa Grande, Rizal moved to his seaside hacienda in Talisay, which formed part of the 16-hectare land he bought after winning the lottery. His hacienda eventually grew to almost 80 ha.

Casa Cuadra, which served as Rizal’s main residence, stood on an elevated ground with an open view of the sea and full protection of the hill behind it. A veranda encircled the whole house. Coconut leaves, which were abundant in the area, were used for the house’s roofing.

Rizal won the hearts of the townspeople with his medical practice with no fees for the indigent. After operating on a rich Englishman with cataract and got paid P500, he provided Dapitan with street lighting with coconut-oil lamps.

Throughout Rizal’s four-year stay in Dapitan, he also remodeled the town plaza, constructed a reservoir to give the area a water system, had put up a school and dormitory for bright boys in Talisay, and established a clinic where he treated ailments and performed eye surgeries.

Fort Santiago

Fort Santiago in Intramuros, Manila was declared a national shrine known as the “Shrine of Freedom” in memory of heroic Filipinos who were jailed or killed there by the Spaniards and Japanese. Its most famous prisoner, perhaps, is national hero Jose Rizal, who was there until his execution on Dec. 30, 1896.

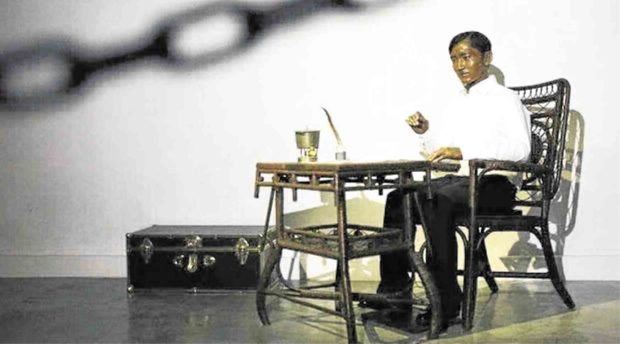

On Nov. 3, 1896, a closely guarded Rizal was brought to Fort Santiago, a place he was familiar with, as he was taken there in 1892 prior to his exile in Dapitan. Rizal, held incommunicado, spent his final days in this jail comprised of an anteroom and an adjacent bedroom. It was in his prison cell where he composed his valedictory poem, “Mi Ultimo Adios.”

Today, his actual prison cell is one of the galleries at the Museo ni Jose Rizal in Fort Santiago, along with other galleries containing relics reflecting Rizal’s life, achievements and last hours before his execution.

After its destruction in World War II, Fort Santiago was declared a national shrine under Republic Act No. 597.

Its reconstruction followed in 1953.

“It shall be reconstructed as closely as possible along the lines of the original structure, and its surrounding shall be reserved for a national Plaza of the Unknown Hero, which shall include the Ayuntamiento, and the site occupied by the former Palace of the Spanish Governors-General,” the law stated.

Sources: Inquirer Archives, The First Filipino: A Biography of Jose Rizal by Leon Ma. Guerrero, philembassymadrid.com/rizals-madrid, NHCP website, Nick Joaquin’s Rizal in Saga, In Excelsis: Jose Rizal