A visit to rural Malaysia

In mid-July, I was part of a small Davao group that visited Malaysia to learn more about its rural development models and how these contributed to reducing rural poverty. We met with top officials of the Federal Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority (Felcra) and the Federal Land Development Authority (Felda).

Felcra is mandated to consolidate and rehabilitate mostly small landholdings. In the 1960s, there were serious problems that arose because of the limited area sizes as well as fragmentation. By 1995, Felcra has helped 91,000 settlers spread over 267,000 hectares (ha).

Meanwhile, Felda is the land agency that developed new lands (mostly forests) for poor settlers in large schemes from 1957 to 1991 and benefited some 113,000 settlers in 480,000 ha. Felda ended its settlements program in 1991.

My visit was a sentimental one. I served as an agriculture project economist with the World Bank in Washington, D.C. My last four years there from 1979-83 were spent on Malaysia projects.

My job entailed project supervision of unfamiliar names to outsiders such as Muda, Krian-Sungei Manik and National small irrigation projects as well as Northwest Selangor, Western Johore, Kedah Valleys and Malacca Agriculture Development Projects. Rubber, oil palm and rice were the main crops.

During my World Bank days, I visited 12 out of the country’s 13 states. There were periodic meetings with the Economic Planning Unit of the Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Agriculture, Drainage and Irrigation Department, State Planning Units, Rubber Industry Smallholders Development Authority, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute and Felcra. (Note: Another colleague in my division dealt with Felda projects).

Felcra was established in 1966 to rehabilitate or develop state land schemes with the approval, or at the request, of the state government concerned. It was also allowed to rehabilitate or develop privately held lands, at the request of owners on agreed terms, as cited in a World Bank Appraisal Report in 1981.

Project history

The Trans-Perak Area Development Project was the first World Bank-financed project of Felcra. Three more projects followed. It was appraised in February 1981, a good 36 years ago. I was the team leader.

The project would provide for the development of 14,800-ha of new land for rice and tree-crops and for rehabilitation of existing rice land of 3,700 ha. The proposed project combined land rehabilitation and new land development for 6,900 families with 1.2 ha of irrigated rice land and a 1.2 ha share in tree crops.

The project focused on the major rural poor, the rice smallholders, and addressed two of the constraints in achieving an income above poverty level: small size of holding and low productivity of land.

The rural poverty incidence among agriculture households was 55 percent in 1978; while those of rice farmers, 74 percent. According to a World Bank report, for a rice farmer with 1.2 ha to earn above poverty line, he must have two crops of rice a year plus the same amount of income from off-farm work.

The main project components were: (a) construction of irrigation canals and drains; (b) development of 6,400 ha of new land for rice irrigation; (c) rehabilitation of 3,700 ha of existing rice lands; (d) crop establishment of 8,400 ha of tree crops; (e) project main roads; and (f) palm oil mill.

The settlers would be entitled to a loan covering costs of crop establishment and housing. Felcra would deduct loan repayments for land development, and housing and subsistence allowance in the early phase. Housing would be payable for 15 years with a two-year grace period. Land development was payable in 20 years with 10 years grace period on principal and interest.

Agriculture production

The rice yield of 2.8 tons/ha at the start of the project was expected to increase to 3.8 to 4.2 tons/ha per crop at full development. The average yield today is 6 tons/ha per crop under mechanized operations.

Some 90 percent of the settlers had incomes of MYR250 per household per month compared to the poverty line of MYR350 per household per month at 1981 prices.

The project cost was $200 million and the World Bank covered $50 million. Project development would be via private contractors. At project completion in 1988, project cost was reduced to only $104.5 million and the final World Bank loan amounted to $30.6 million due to cost savings and restructuring. The economic rate of return was very satisfactory.

Trans-Perak at completion (1989)

Despite problems in the early parts of the implementation, the project was an overall success and increased productivity and incomes of settlers. At project completion in early 1989, rehabilitated rice land totaled 4,035 ha (109 percent of appraisal target); new rice area, 4,353 ha (68 percent appraisal target); and tree crop area, (mostly oil palm) 8,218 ha (97 percent of appraisal target), based on the project completion report in 1989. The economic rate of return was very satisfactory.

Trans-Perak now (2017)

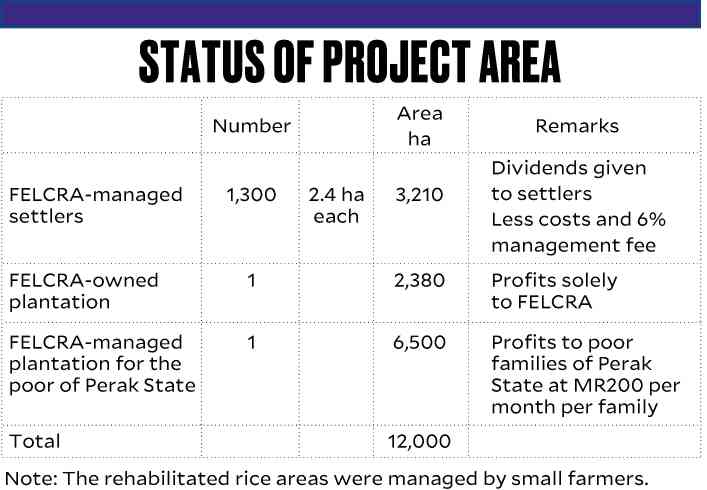

The project design has indeed changed. There are now 4,000 ha of mechanized rice estates, and 8,000 ha of oil palm plantations. The land allocations are: 3,120 ha for the 1,300 settlers; 2,360 ha of Felcra corporate plantation, and 6,500 ha of Felcra-managed plantations for the poor of Perak State. Felcra charges a six percent management fee. The rehabilitated rice lands under existing farmers fell under the extension services of the State Department of Agriculture.

Today, Felcra settlers earn about MYR1,600 a month (equivalent to P19,000) per family: MYR550 from dividends and about MYR1,050 from wages. The poverty line income for Malaysia is MYR800 (P9,600) per household per month. Many of the settlers’ children have families and completed college education. (Note: a Malaysian ringgit is about P12).

The amount excludes incomes from remittances from children who are mostly professionals as well as from small businesses.

Development Lessons

The successful Malaysian rural development strategy through managed land schemes provides lessons for the Philippines. The rural poverty incidence in Malaysia was 1.6 percent in 2014 down from 58.7 percent in 1970 and 19.3 percent in 1990. Compare these to the Philippines’ 30 percent in 2015.

The father of Malaysian development, former Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak, had espoused the use of modern plantation management for government land settlements to achieve high productivity and, in turn, reduce poverty. He advocated the idea of giving the best lands to those willing to work hard. There are six important lessons:

1. Crop choice is critical for long-term income sustainability. Malaysia started with rubber as the main crop and later changed to labor-saving and more profitable oil palm. Rice, an exception for food security, was managed on mechanized estate basis.

2. Modern plantation management is key to achieving high productivity. Farm productivity in managed schemes must match that of commercial plantations.

3. Farm consolidation is crucial to achieving economies of scale in management pool, input supply, mechanization and marketing.

4. The leadership was focused on project implementation.

5. A professionalized civil service to draw project managers.

6. Commitment from the top is key to achieving results.