“There’s no place like home” is an adage that resonates well with recently launched chocolate brand Auro.

After all, the partners behind this business, who came back to the Philippines specifically to set up the company after studying and working abroad, are keen on making high-quality products that are truly “made for Filipinos, by Filipinos.”

Labeled as a “bean-to-bar” chocolate company, Auro is rooted in the philosophy of genuine inclusive development, says its managing directors Kelly Go and Mark Ocampo.

By sourcing directly from local farmers, the 27- and 28-year-old, respectively, are also working on improving these farmers’ processes and skills to enable them to produce higher-quality cacao.

Auro’s goal, ultimately, is “to be known as the best Filipino chocolate company that crafts truly single-origin products that are grown, refined and perfected in the Philippines—while providing sustainable livelihood for the farmers we support.”

“There’s this predominant mentality that imported is always better—for everything. I’ve talked to chefs whom we thought would be resistant [in using local cacao], but they all unanimously want to use local, not just for chocolates; there’s just this concern about quality, availability and price,” says Go. “So what we’re trying to do with our brand is to make sure that all of those are aligned.”

Go and Ocampo met in Chicago, where they both studied for college, over seven years ago.

Go was then finishing her degree in Political Science and International Studies at the University of Chicago; Ocampo, on the other hand, was taking up Advertising and Marketing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The idea to open their own fine chocolate company came from Go’s mom Jacqueline, after discovering around six years ago that artisanal chocolate being sold in the US used cacao beans from Davao.

“She was surprised because it meant people were sourcing pretty good cacao from Davao, which we didn’t know about,” says Go.

So Go’s mom, a chef and engineer who’s also a kitchen consultant, headed to Davao to see for herself what sort of cacao was available there—and discovered, by talking to local farmers, that what could have been a national treasure, in the form of the extremely rare criollo porcelana variety of cacao, had been taken for granted for centuries because of the farmers’ lack of knowledge of its worth.

“[My mom] just had a hunch that we had it, and [finding] it was like a treasure hunt, because the sad part is a lot of the farmers already cut down their trees… because no one really recognized the value,” says Go, who, in the course of their research, found out that criollo porcelana had been available in the country since the 1600s.

“I don’t think it happened quickly, that they decided to just cut it down,” says Ocampo. “You have three main varieties, [which are] forastero, trinitario, and criollo. Trinitarios are cross-pollinated forastero and criollo. Bigger companies started bringing in more of the trinitario, so over time, that was what they propagated here in the Philippines. At some point prices dropped, and so what ended up happening was that farmers didn’t really have a steady source of income, and the effect of that was they had to cut down the [criollo] trees.”

“And no one was paying them for the criollo,” adds Go. “So my mom started to encourage them to propagate [criollo], and told them that she’d buy at a much higher price.”

The initial idea was to just put up a small chocolate shop, says Go, who by then had already started to become involved with the business, as she also went to culinary school after graduating from university.

“But my mom said, it’s not going to be enough for us to put up a small shop. The reason why the market [for local cacao] keeps fluctuating so much is we don’t have enough local demand for good cacao, and local production. So in order to keep [the business] sustainable, we have to make sure the demand is here for the raw material, not just to have it exported,” she says.

Enter Ocampo, who at the time was already holding a directorial position in Ogilvy & Mather in Chicago, handling international brands such as Unilever and SC Johnson. He had also done brand work for some of the US’ most influential personalities such as Elon Musk, Tory Burch and Alexander Wang—but Ocampo felt something was amiss.

“I knew I never really wanted to stay in the States. [I wanted] to go back home and make a difference,” says Ocampo.

Go says she slowly and subtly introduced the business idea to Ocampo, mentioning it casually during one of their Thursday night cookouts back in Chicago, and even taking trips to cacao trade shows.

“It was such an interesting project, and the possibility of going back to the Philippines, not to mention being able to work with my best friend… for me, it was very clear that I wanted to partner with Kelly to be able to do this together,” Ocampo says.

To improve their knowledge of the technicalities of the cacao industry, the two took a course in Germany on industrial chocolate production.

In 2015, they finally came home to put up Auro.

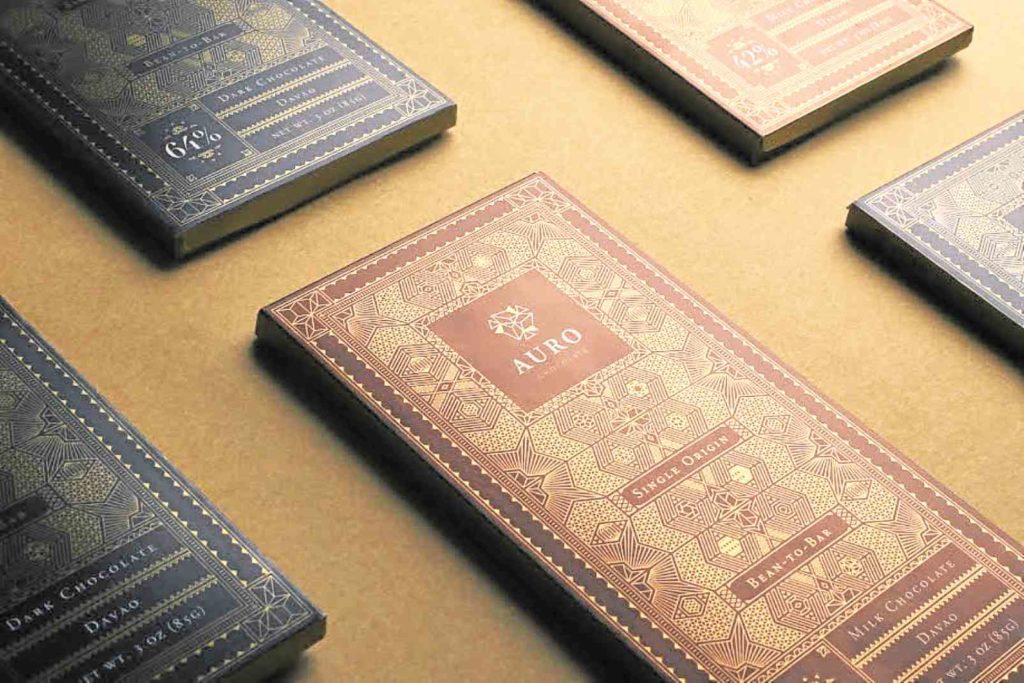

With gold as their inspiration (Au is its chemical element symbol, while “oro” is Spanish for gold), the two came up with the brand name because of their discovery of criollo and its relevance to our cacao heritage. They believe they are basically just refining, polishing, and transforming a long-lost treasure that’s as “remarkable as gold.”

Go and Ocampo work with around 10 cooperatives and a few individual farmers from Davao. To motivate them to improve their harvests, the partners have come up with a unique incentive program, which affects how much they will pay for each farmer’s cacao beans.

“To make a difference in the industry, we found that there are many ways to create price incentives determined by the quality of the cacao that you produce, dependent on the percentage of defects of the cacao and how it will affect the flavor of the chocolate,” Ocampo explains. “We created this price matrix that basically is divided into the different varieties of cacao—forastero, trinitario and criollo—and there’s a parameter that we set for the maximum amount of defects. If you exceed that, it either goes down a tier or we reject.”

Their chocolate products, which they plan to sell both in retail and wholesale, are manufactured in a factory in Calamba, Laguna, which can produce up to 1,000 tons per year, says Ocampo.

As they continue on their quest to contribute to the advancement of the Philippines’ cacao industry, Go and Ocampo say they also make it a point to continue learning best practices from other countries.

Go’s mom also continues to guide the two as they grow the business.

[We take] every single opportunity we get to meet with cacao farmers around the world, and it’s amazing because we’re still so young,” says Ocampo. “There’s still so much that we’ve yet to learn. We want to have the Philippines be identified as a country that values quality, and wants to create a name for itself in the cacao industry.”