5 things you didn’t know about the Edsa Shrine

My husband, Arch. Bobby Mañosa, designed the Shrine of Mary Queen of Peace, or the Edsa Shrine more than 30 years ago.

While all his projects come with interesting stories from behind the scenes, the Edsa Shrine has some of the most memorable. Here are some that are known to few.

The original site for Edsa Shrine was in Camp Crame

When Cardinal Sin approached Bobby with the project, the proposed site was a 5,000 sqm plot of land inside Camp Crame. It turned out however that any church built on government land had to be ecumenical—it could not be just Catholic.

Thus, the site moved to the corner of Edsa and Ortigas Avenue, on land donated by the Ortigas family. John Gokongwei donated additional land to provide more space.

The new lot measured 2,600 sqm, half the size but in a much better location—the very spot where hundreds of thousands of Filipinos had converged to clamor for democracy.

The church was initially designed to be above ground

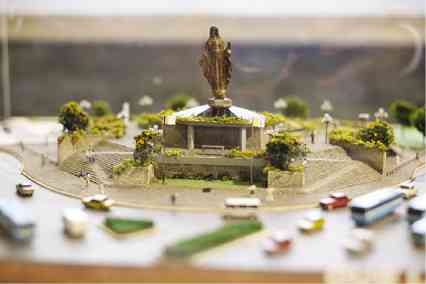

Bobby’s vision for the Shrine was a “People’s Basilica” with the structural outline of a bahay kubo but on a grander scale—with seven pitched roofs clustered together, framing a statue of the Blessed Virgin.

Bobby walked out on the project after his first presentation

The first design was disapproved, as an influential member of the committee preferred a Spanish design for the church.

Bobby—whose battle cry was “I design Filipino, nothing else”—was strongly against this. He said: “A Spanish colonial church commemorating a Philippine revolution on Philippine soil? Never!”

He rolled up his plans, saying, “I believe I am not your architect. I cannot do that to our country or to our people…” and walked out in the middle of the meeting.

Cardinal Sin followed him outside and asked him to reconsider, and he did.

With the “People’s Pavilion” no longer a possibility, Bobby compromised with a “People’s Plaza”—a promenade with the Blessed Virgin as the focal point, and an underground church inspired by the Cathedral of Brasilia. It was no bahay kubo, but neither was it Spanish colonial. It was a modern concept, one well suited to what the space stood for.

The sculpture of the Blessed Virgin could have looked completely different

Napoleon Abueva was Bob’s first choice for the sculpture. Unfortunately, the artist was recuperating from a stroke at that time. So he turned to Manny Casal to create it instead.

Casal’s sculpture was to be a gentle looking Virgin Mary in marble, with arms open as if comforting the people below her—lay people, clergy, children, soldiers. It was a representation of the diversity of people who came to Edsa.

Casal’s plan was to sculpt it onsite, so passersby could see and drop off contributions if they wished.

The commission ultimately went to Virginia Ty-Navarro—the committee’s choice—but Abueva and Casal created other sculptures found in the Shrine.

Despite mixed reviews, Navarro’s Blessed Virgin has been remarkably resilient

Virginia’s sculpture was created in her studio in San Juan. They belatedly discovered that the roads were too narrow to maneuver the truck that would be required to transport it to the Shrine. So the sculpture was airlifted by helicopter, with the help of the US Embassy.

The sculpture not only survived that, but also other potentially destructive events.

Fielding criticism from the press, one attempt by Navarro to make changes to the Blessed Virgin’s face was foiled by a freak cyclone, which had toppled the scaffolding two hours before the work was to begin.

Yet the Virgin’s brass robes, declared too thin by consultants and predicted to break by the first typhoon, have never once been broken over the years and events that followed.

Coincidence or divine intervention—who knows. Given the venue, it would be nice to assume the latter.