They are tagged with names different from their own

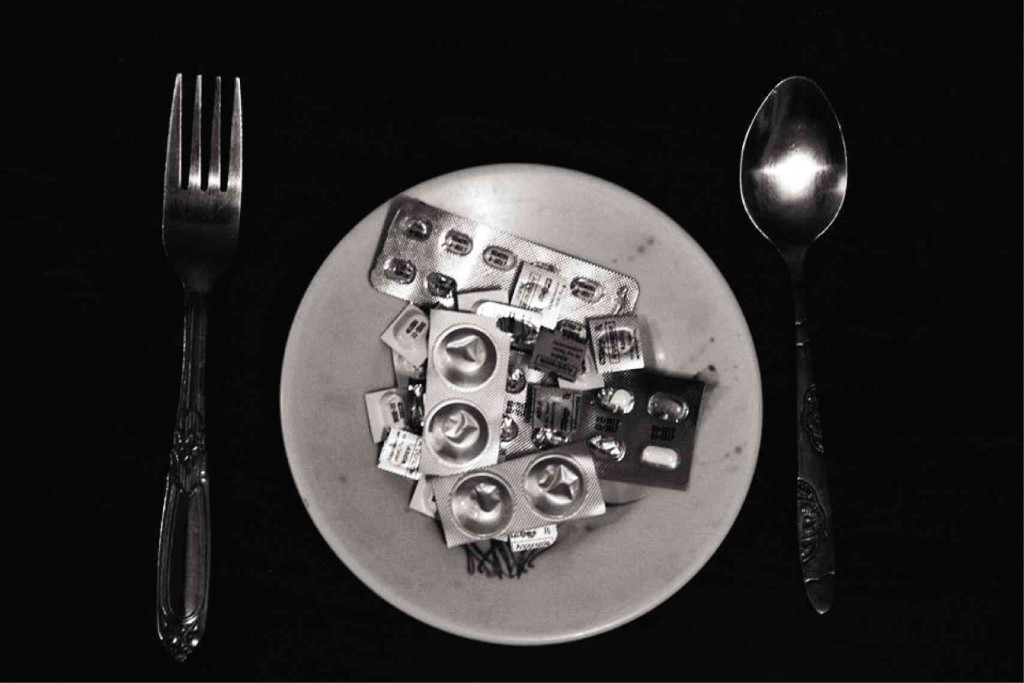

A DIFFERENT KIND OF MEAL A plate contains medicines for bipolar disorder. Daily maintenance drugs per person may cost as high as P500. JANUARY TURLA

(First of three parts)

They call it Ward 7.

It was the first day of the week, and the sun was sending warmth and light from the large window panes to beds covered in white sheets. No cries of pain, no signs of suffering reverberated along the corridors.

What’s more apparent is silence, broken only by feet aimlessly pacing back and forth the wide hallway of the free ward in a fashion brought more by boredom than mindlessness. Some cover their faces in anxiety; others sit quietly on their place. They are the patients tagged with names different from their own, but more often these names are understood only by a few.

Every morning, they all wake up early with a barrage of noise from the nurses for a physical exercise. A list of daily tasks —psychoeducation, art education, etc.—is posted on the bulletin board near the entrance to encourage them to socialize. Most of the time, they are not glued in beds and are free to wander inside the ward. The doors are always open, but somehow they knew they don’t have the freedom to walk out.

Later in the afternoon, a nurse approaches them one by one to ask a generic set of questions: “What is your name?” “How old are you?” “How are you feeling today?” “How did you get here?” These are the questions they are being asked over and over each day, as if the mere act of answering is a daily affirmation of being OK, at least for the meantime.

In a visit in October last year, the psychiatric ward of the Philippine General Hospital (PGH) was home to 12 mentally-ill patients—most of them young. But they are all part of a bigger statistics.

According to the 2014 Health for the World’s Adolescents of the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the predominant cause of illness and disability for boys and girls aged 10-19. In 2011, the WHO found that 16 percent of Filipino students aged 13-15 had “seriously” contemplated suicide in the past year. Meanwhile, 13 percent had actually attempted suicide.

And yet one doesn’t need to look very far to understand that the problem exists close to home. Almost one per 100 households (0.7 percent) has a member with mental disability (DOH-SWS 2004). Intentional self-harm is the ninth leading cause of death among 20-24 years old (DOH 2003).

You may call them names: crazy, lunatic, insane. But their stories are not the same.

Miracle in Ward 7

“It’s like… asking for miracle in Ward 7,” said Vlad, 24. It was somehow a reference to a sentimental Korean movie, “Miracle in Cell No. 7.”

He’s been inside the ward for more than a month, way beyond the two weeks prescribed by psychiatrists at PGH before patients can be integrated again to society. He wanted to go home but right now there is no certainty he could.

Vlad was diagnosed as bipolar. Bipolar disorder, also called manic depression, is a long-term condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). It can be controlled with medications and psychological counseling.

He would usually be found walking around Ward 7, always deep in thought but ready to engage one in a conversation.

“Napanood mo na ba ’yung ‘Transcendence’ ni Johnny Depp (Have you watched “Transcendence” by Johnny Depp)?” he asked randomly, then proceeded to narrate the plot of the film.

“Ano’ng pangalan mo? Ilang taon ka na? (What’s your name? How old are you?)”

“Marami kasi akong bisyo. Sabi ng psychiatrist ko, kapag inulit ko pa yung bisyo ko, ililipat na ako sa mental hospital talaga (I have a lot of vices. My psychiatrist told me that if I engage in a vice again, I’ll be sent to a bigger mental facility.”

“Bakit sa Roxas Boulevard maraming nagba-bike? (Why does Roxas Boulevard have a lot of bikers?)”

He is always asking questions—never mind the coherence. His thoughts may be scattered in fragments, but he knows what he wants, swirled in whatever he is missing: the outside world, his family, his girlfriend, his dreams.

Asked what he wanted to do when he gets out of the ward, he said: “Gusto ko muna magtapos ng high school. Kasi mahalaga ’yung pag-aaral, eh. (I would like to finish high school first. Education is important.)” He wanted to be freed from the daily existential chain inside the ward, but the people there have become family to him, especially Tatay Nicolas, a schizophrenic and the oldest patient in Ward 7.

The sound of silence

There was a boy named Hardee. He was an interesting teenager, in an intensity that also transcends in the way he talks to strangers. Most days, he appears no way between sad and gloomy. He would readily engage you in small talks (“Anong sinusulat mo? Tungkol sa AlDub?”) with his boyish grin and enthusiastic eyes. He likes to tell stories even without you asking.

Three years ago, he began hearing voices inside his head. He was diagnosed as Bipolar II. Just recently, the voices became a recurring presence and he found himself in Ward 7 for the second time.

He is 22 and in his second year of business management course. But because of his condition, he had to stop. Instead of books and pens, his tools to get by each day are six types of drugs—only that he chose to stop taking them because he doesn’t like the side effects.

He has just been readmitted to the ward after his out-on-pass, a two-week program granted to patients to test if they can handle life outside the ward again. Now all he wanted is to go home. But for how long he would stay inside Ward 7, he doesn’t hold the answer.

He likes to tell stories. But not that day. “Nalulungkot talaga ako. Gusto ko sanang magkwento kaso nalulungkot ako ngayon eh (I feel really sad. I would love to share stories, but right now I am sad),” he said. He slumped on his bed, closed his eyes, and was reduced to silence.

But silence couldn’t be more profound with Lea (not her real name), 16, the youngest patient inside the ward. She was a rape victim.

She stopped talking after the horrible incident. She wouldn’t speak and eat; food was forced into her body through an NGT cable. Yet her presence is the most striking in the entire ward as she would look at you sharply, her silence too piercing and more powerful than words. Somehow, this guards her from the world she can no longer trust as it also cloaks her fear beneath her little body.

Her mother never leaves her side, always patient and hopeful that her daughter would speak again. She never gave up on her. Each day, she would tell Lea stories and jokes. She would teach her how to write and smile again.

“Dapat dinadaan natin sa joke, hindi natin pinapakita sa kanya na malungkot tayo,” said her mother. She smiled but was almost in tears.

That day, it was Lea’s first time to write her name again. It took her an hour to scribble her name on paper. She even managed to write the lyrics of “When You Say Nothing At All” by Ronan Keating on a white sheet. She had a fine handwriting; after all, Lea is a smart child. She was an honor student with grades consistently in the 90s in high school.

They’ve been inside the ward for a month, and Lea’s birthday is in three days. But there are still a lot of questions none of them, even her doctors, know the answers to.

In a note she gave her psychiatrist, Lea wrote: “Doctor, ano pong sakit ko? (Doctor, what is my illness?)” then she left a blank after the question. It was a blank that’s never been filled.

Later that day, she was found sitting at the edge of the bed, busy on a word search puzzle. Her mother, sitting beside her, serves as her second pair of eyes. After some time, she finally found a word, and with hesitation put the tip of the pencil on top of it and encircled, “trauma.”

There are many times when they try to tell themselves that they’re OK, but even then being OK is an uncertainty none of them can take control of. What they have is a mental illness: a legitimate medical concern that deserves to be treated, and no amount of individual conviction of being OK can ever alter.

But until this day, they can only wait to deal with the next attack as they struggle with the social and economic costs of their condition: stigma, expensive medicines, and high medical risks.

Lack of priority

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and right,” states the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But the current mental health scene in the Philippines shows otherwise.

“Health,” as defined in the WHO Constitution, is “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

Philippine Psychiatric Association former president Edgardo Tolentino, MD, reports that while the country has signed commitments to international covenants and agreements, it remains without a mental health bill despite the rising mental health problems and a constitutional mandate to protect the rights of all.

The lack of attention given to mental health is reflected in the “insufficient, inequitably distributed and inefficiently used” resources for mental disorders.

A 2007 report of the WHO reveals that “the country spends about 5 percent of the total health budget on mental health, and substantial portions of it are spent on the operation and maintenance of mental hospitals,” which are concentrated in the National Capital Region.

The ratio of human resources working on mental healthcare and the country’s population is 3:100,000.

Dr. June Lopez, a professor of psychiatry at UP College of Medicine and an expert member of the UN subcommittee on the prevention of torture, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, said a mental health law is an urgent imperative to address these concerns.

“We need a mental health law because we’re one of the few remaining countries that doesn’t have one, so we have no guide on protecting rights of the patients and mental health professionals,” she said.

READ: Mentally-ill individuals still functional despite ailment