When the chips are down, can you rely on ancient navigation?

Ours is an archipelagic country, and we are a nation of seafarers. Our seamen are in demand among ocean-going vessels—because they are the best.

I have it on reliable authority that at least one-third of all the ships that navigate the world’s oceans are manned by Filipino crews.

The knowledge and skill of Filipinos in navigating the seas has been legend. The Muslim vintas, which antedate the “discovery” of the Philippines by the Spaniards, are renowned for their speed, agility and balance.

It is told that our seafarers before we were “colonized” could sail from one island to the other with very little navigational instruments—relying on their reading of the stars and on their sharpened instincts.

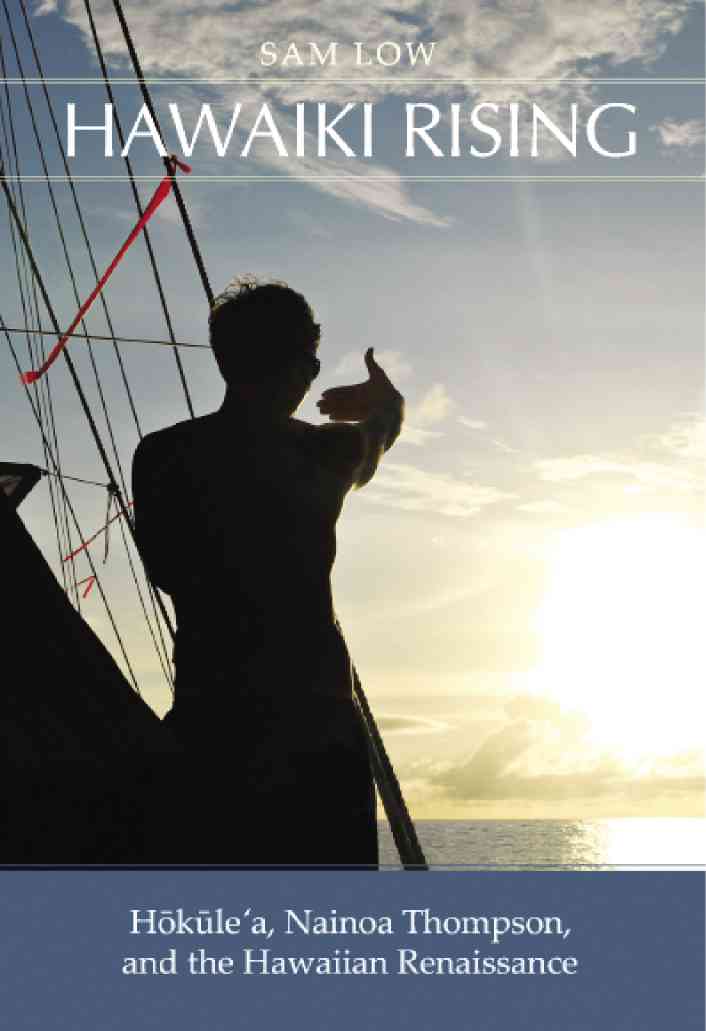

These thoughts come to mind upon reading “Hawaiki Rising,” a riveting narrative on the voyage of Hokule’a, a canoe, inspired by Polynesian boat design.

The vessel is described by Wikipedia thus: “In proper maritime parlance, Hokule’a is a double-hulled Polynesian voyaging canoe, but any yachtsman would immediately recognize her as catamaran. (Catamaran is described as a multihulled vessel consisting of to parallel hulls of equal size.)

The book gives a bit of history: “In Polynesia, such craft was invented thousands of years ago—during a time when ponderous single-hull vessels were evolving in the western world.”

Polynesians could not fashion large European style plank-on frame ships, and they knew that small outrigger canoes would not be seaworthy for long voyages.

“So, someone thousands of years ago, thought of bridging two canoes with a solid deck. Lo and behold! “An advanced sailing craft was born out of necessity confronting the limits of primitive technology,” the author says. Once again, the adage, “Necessity is the mother of invention,” holds true.

According to the book, the Hokule’a made two voyages. The first one was from Hawaii to Tahiti in 1976, when the canoe’s journey was filmed by a National Geographic crew. The return trip—from Tahiti to Hawaii—was made in 1982, and was featured in a film called “Pathfinders of the Pacific.” In each voyage, the crew decided to use ancient skills, minus modern navigation instruments.

Mau Piailug, a Micronesian navigator, guided the canoe toward Haiti. Piailug is a practitioner of the ancient way of navigation. Piailug has mentored a lot of graduates in ancient seafaring, some of whom continue to draw students on the old ways of navigation.

In this book, there is poetry in telling the story of the journey: “Hokule’a forced her way north, close hauled, into a 20-knot easterly wind. Her crew watched the mountains of Tahiti sink slowly below the horizon. Clouds were stacked up over the mountains and the light, reflecting from the lagoon, painted their underbellies a faint blue-green.”

Aside from reaching its destination, the feats of the double-hulled canoe gave the motley crew of Polynesians (Hawaiian, Micronesian, Tahitian, et al) a chance to rediscover themselves, feel the “presence of their ancestors,” be proud once again of their navigational heritage.

The value of this book, aside from its narrative power is the challenge it poses to so-called modern navigation. This is told by the author, who is a former navy man and a Ph.D. in anthropology from Harvard University.

While this true story is punctuated by the human dynamics of adventure, sacrifice, daring deeds and triumphs, a parallel thread of thought is unraveled – and it is this:

Every people and every state must revisit its history of navigation, find out new details about collected knowledge on how its seafarers braved the seas, navigated with guidance from the stars with a crew who attuned—heart and soul—to their ocean surroundings.

By doing so, a wizened people can rediscover their almost forgotten ancient story of navigation—and so stumble upon an astonishing truth: seafarers, particularly Filipinos, are governed by a different “science.”

While the book describes the Polynesian way of navigating and be useful to maritime experts and students, the book also points the reader to one possibility that must be faced: When modern instruments fail, due to a lack of electric power, how will one navigate?

The true-blooded mariner will be left to his own resources and devices. Then he resorts to the ancient way of navigation. He will be attuned to what Nature is telling him. He will follow signs and rely on his own senses.

For example, at sunrise, he observes that the sun is shining over the sea. He further notes that it is bright on the right side and on the left side. He notes though that the middle part of the sea is dark. So he decides to steer the boat toward that dark patch. Why does he do that? Because he concludes that there something that’s blocking the sun’s rays.

From his expert’s eye, he knows there is an island – even if it is still below the horizon!

Clearly, the book has narrative power, with a gripping story. Even if you are not a seafarer or a merchant marine expert, you will enjoy this book.

You will learn more from this book—the technical difference between ancient versus modern navigation, for instance.

There is a bit of irony that our maritime capability leaves much to be desired, considering that Filipino officers and crews are manning one third of the ocean-going vessels around the world. This is according to my friend, Napoleon Curameng, whose enthusiasm for navigation has not waned.

Come to think of it. Filipino seafarers should have the same project like the Hokule’a journey, so that they too will rediscover our rich maritime heritage. For starters, they may check a recent archeological finding in the Philippines which revealed some artifacts of a boat similar to the Polynesian canoe.

The book, titled “Hawaiki Rising,” may yet have a sequel written about our own ancient navigational system leading to the prospects of “Philippines Rising.”

E-mail dmv.communcations@gmail.com