Emerging heart disease risk

Among cardiologists, there has been a lot of talk lately about a substance produced in the body called homocysteine and its relationship to the development of deadly heart diseases.

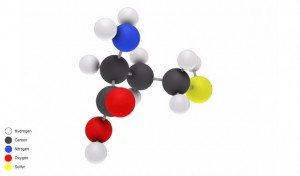

Homocysteine is an amino acid—one of the building blocks of proteins—and having high levels of such has been attributed to the early development of atherosclerosis or the clogging and hardening of one’s arteries.

Atherosclerosis is one of the most important and common causes of death and disability throughout the world. A number of landmark studies have been conducted in the United States—Framingham, Massachusetts; Tecumseh, Michigan; and Chicago, Illinois. These studies have attributed its development to several factors, namely: (nonmodifiable) age, gender and heredity, as well as (controllable) having high blood pressure or high cholesterol levels, smoking tobacco, diabetes, sedentary living, having chronic emotional stress, obesity and having “sticky” blood.

However, Dr. Adolfo B. Bellosillo, head of the Makati Medical Center’s Cardiac Rehabilitation and Preventive Cardiology Unit, noted another emerging but unacknowledged factor.

Bellosillo reported that he has been encountering a number of patients without the usual symptoms. He reminisced: “I once had a 21-year-old patient, a tricycle driver, who was rushed to the emergency room after complaining of a crushing pain in the chest. He was sweating cold and suffered from low blood pressure. Interestingly, his family had no history of sudden death, heart attack or stroke, and he was physically active, a nonsmoker, not even diabetic or hypertensive. And yet, his electrocardiogram test confirmed heart muscle damage, which was corroborated by a blood enzyme that tested positive for heart attack.”

Article continues after this advertisementAnother case

Article continues after this advertisementThe doctor cited another case involving a 24-year-old postman who, while playing basketball, suddenly felt chest heaviness and cold sweats. “Like the first case, his electrocardiogram showed heart attack, which was again confirmed by a blood enzyme test,” he recalled. “Like the first case, his risk factor profile was practically negative,” he added.

Bellosillo said that baffled about the second patient’s medical profile, the emergency room doctor decided to have the patient’s homocysteine levels checked. He said: “As suspected, the level was high. I realized that there appears to be a strong link between having high homocysteine levels and damage to the arteries that could lead to atherosclerosis, the formation of clots, and the eventual occurrence of heart attack.”

Bellosillo, who is also the founder and president of the Foundation for Lay Education on Heart Diseases, was wondering why it was not included in the usual list of risk factors established by the landmark studies.

Bellosillo said: “These two cases make one think that there may be risk factors for atherosclerosis that were not somehow uncovered by these landmark studies. This only means there are other groups of different genetic makeup, exposed to different environmental conditions, nutrition, etc. that could still develop atherosclerosis and later suffer from heart disease. Knowing the nature of the subjects included in these studies, one cannot help but raise the question of the universality of these ‘Western’ risk factors disseminated by these studies.”

Further confirmed

Bellosillo’s concern was further confirmed when recent studies found that the risk of heart attack was threefold higher in subjects with homocysteine levels in the top 5 percent of values, compared to subjects with homocysteine in the bottom 90 percent. Subsequently, a number of other studies have concluded that high homocysteine levels represent an important independent risk factor for coronary heart disease, heart attack, stroke, peripheral atherosclerosis and venous thromboembolism (the blockage of a blood vessel by a migrating clot).

Bellosillo said: “No wonder the International Task Force for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases in Europe recommended that homocysteine be measured in patients with history of atherosclerosis and/or those with blood vessels clogged with clots. The same task force recommended that individuals with homocysteine levels greater than 12 micromoles per liter should increase and/or supplement dietary intake of folic acid; and those with levels greater than 30 should be treated with daily doses of folic acid, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12.”

Already practiced

The doctor was glad that while measuring homocysteine levels is hardly available in the country, a number of hospitals including the Makati Medical Center have been performing the test for quite a while already, with many of the requests coming from cardiologists, neurologists, nephrologists and internists.

Bellosillo said: “So far, studies to determine whether lowering homocysteine levels can reduce the risk of heart disease haven’t shown a benefit, but this may be because the studies were too small or because homocysteine levels weren’t lowered enough. However, with folic acid, vitamins B6 and B12 widely available and very inexpensive, management of patients with cardiovascular diseases due to elevated homocysteine becomes easier and very affordable especially to the population in developing countries such as ours.”

He added that it is reasonable for high-risk patients with high homocysteine levels to increase their intake of B vitamins. “These vitamins can be found in a wide variety of fruits, green leafy vegetables and grain products fortified with folic acid,” he said.