Trading freely or fairly?

Is free trade fair trade?

Both free trade and fair trade seek to help farmers and other producers reach the global market and improve profit for them.

The ways they pursue this objective, however, vastly differ.

Free trade upholds a policy of nondiscrimination against imports and noninterference with exports and does so by doing away with tariffs (to imports) or subsidies (to exports) or quotas.

Free trade allows trading partners mutual gains from trade of goods and services as they, regardless whether they come from a poor or rich country, transact business on a level playing field. Advocates of free trade believe it is the best way to match global supply to demand while making all people involved more prosperous.

Fair trade, on the other hand, is a social movement that aims to help producers in developing countries negotiate for better trading conditions. It advocates the payment of a higher price from buyers to suppliers, known as “social premium.” Thus in fair trade, the field is deliberately tilted to favor producers from poorer countries, provided they comply with certain social and environmental requirements.

The terms of fair trade apply especially on exports from developing countries to developed countries, notably: Handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, honey, banana, cotton, wine, fresh fruit, flowers and gold.

Speaking for free trade

In her book “This is my voice: I speak for fair trade,” Elena Sen Lim, well-known Filipino entrepreneur, pushes for fair trade as the system that should be embraced by the Philippines.

In real practice, the discrimination and interference that free trade purports to eliminate still persist, she says. “Governments employ both overt (e.g. tariffs) and covert (e.g. hidden subsidies) measures to influence imports and exports to favor their respective countries’ interests.”

Free trade perpetrates the subordinate position of less developed countries as a source of raw materials for industrialized countries as well as buyer, importer or dumping ground of finished goods from said countries, Lim writes. Fair trade on the other hand encourages full respect for the right of all nations to fully industrialize.

Lim adds that fair trade upholds the principle of fair competition based not just on compliance with the same trading rules, but also on relatively equal capabilities among the competitors.

Example in a cup of coffee

Dosomething.org gives an interesting illustration of the difference between free trade and fair trade when we one buys a cup of coffee.

A cup of coffee “freely-bought” implies that the producer (farmers, small business owners, manufacturers, etc.) who harvested the coffee beans sold them without the interference of the government, without tax or monetary gifts, without tariffs, subsidies, price controls or pork-barrel politics.

On the other hand, a cup “fairly bought” connotes that the farmer who harvested the beans in a less developed country has been assisted to get his product to the market; it also means the farmer got better trading conditions, including a premium price, in selling his produce.

Thus, by choosing the latter cup of coffee, buyers may see themselves contributing to poverty alleviation in less developed communities. All because they put their money where it makes a difference in the lives of small producers and their workers.

Fair trade in the Philippines

The Fair Trade movement has yet to spread widely in the country, however. There are only approximately 30 Philippine Fair Trade enterprises by recent count.

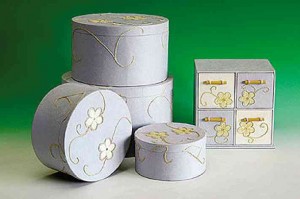

Salay Handmade Paper Products, Inc. (SHAPII) of Salay, Misamis Oriental, is one of the few local companies certified by international fair trade organizations.

SHAPII CEO Loreta Rafisura describes Fair Trade as very “kind and idealistic.”

Fair Trade has helped SHAPII upgrade its social and environmental standards. Fair Trade partners have helped upgrade the business in staff capabilities and other areas.

“The social premium—the higher payment and better trading conditions—has helped us achieve sustainability in the past,” she says.

However, the same premium has jacked up their prices and has made competition, especially with products from China, tough.

SHAPII is 90-95 percent export, of which about 60 percent is with Fair Traders.

Rafisura tries to explain why the Fair Trade movement in the Philippines has not spread as widely as in some other countries.

The movement began in the 40s but came to the Philippines only in the ‘80s. “Perhaps the movement is still new here. Perhaps today’s business climate does not allow practitioners to focus on the advocacy. Perhaps our economy has not permitted it to grow and flourish as fast as in the First World, where they have Fair Trade shops, churches, even Fair Trade towns and universities.”

Because many want to claim they are Fair Traders, the process of Fair Trade certification can be quite stringent especially for small companies. It involves a scrutiny of a company’s mission, vision and activities across all stages of the supply chain, initially by a third party certifier. Once accepted, certified members must measure themselves against 10 standards every two years during social audits.

Networking starts, in SHAPII’s case, from the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) Philippines, WFTO Asia and WFTO Global. “But a whole world characterized by respect, kindness and idealism opens up for members while doing long-term business with partners. They give us support so we can be up to standards.”

“But we are forced to slow down in our advocacy activities because of the difficult export business climate the craft industry is going through.”

“With the continued support of clients, we are focusing on survival in business as we believe that when the ‘Trade’ is down, then the ‘Fair’ also suffers.”

The author is with the Small Enterprises Research and Development Foundation (SERDEF). For more stories on entrepreneurship development and small enterprise management, visit the SERDEF webpage at www.serdef.org.