The essence behind the symbols

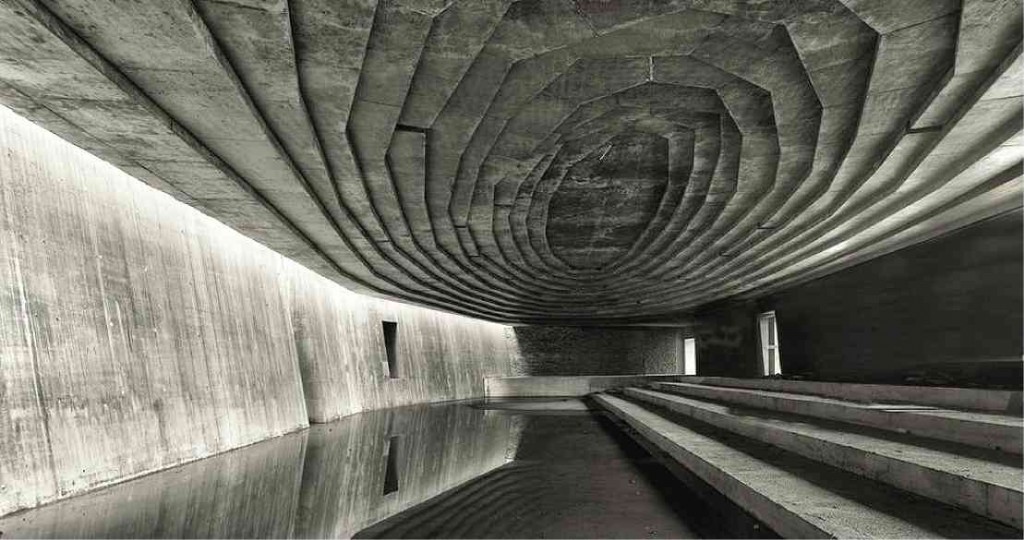

THE INSIDE of the mosque is equally rugged: natural stone and raw concrete is used for almost all its interior surface that stretch covered by a six-meter-wide concrete canopy that mimics the mild slopes of the exterior landscape, a vastness achieved with the modern technology of reinforced concrete that has outgrown the need for a vaulted structural system.

On Tuesday, Nov. 5, the Islamic world celebrates the Amon Hadid, or the Islamic New Year. The presence of the waxing new moon, or a crescent moon, symbolizes the start of the month of Muharram, first of 12 months of the Islamic lunar calendar. Despite its strong presence in Islamic symbolism, scholars argue that the crescent moon has in fact, figured more strongly in other cultures and religions.

The moon is the symbol of Artemis, the Greek female goddess of the hunt, and her Roman counterpart Diana. In ancient Celtic civilizations, the crescent moon signified femininity. In the Chinese culture, it is suggestive of emotions. In early Islam, the symbol defined the conquest of Constantinople, its use possibly evolving from the Ottoman Turks who so widely used this symbol to represent their city. Eventually, the flags of Egypt, Pakistan, and other Islamic nations adapted it into their own.

The domes of the mosques have held the same association to Islam. In Islamic architecture, places of worship have distinct pointed domes, a major structural feature that sets them apart from their western counterparts. In Turkey, the mosques have been built with vast interior spaces, made possible by the extensive use of structural vaults. Framed by towers or minarets, this style of architecture was that of the Ottomans, who mastered this to be distinctly theirs as their empire flourished in what is now modern-day Turkey.

Aside from imposing dominion over the territory, the essence of building mosques was for congregational worship and prayer—and the internalization of the presence of God’s grace (or whatever you would call him in your religion).

Radical breakaway

In Turkey, one particular mosque stands out a as radical breakaway from conventional mosque design. The Sancaklar Mosque designed by Emre Arolat Architects flaunts not only the crescent symbolism now so associated with both Islam and Istanbul but the traditional vaults and minarets so distinct of the architecture of this region as well. This mosque returns to the very essence of worship and religious space, and creates an environment where one can connect to the higher regions of spirituality.

THIS MOSQUE is so unlike its traditional counterparts. It is made of geometric planes that create a half sunken space on a topography that is both harsh yet serene. Its thick walls jut out of the ground and define its boundaries.

Built on a savannah-like environment along a major roadway in the suburban neighborhood of Buyuk Cekmece in the outskirts of Istanbul, the Sancaklar Mosque is so unlike its traditional counterparts. It is made of geometric planes that create a half sunken space. Its planes hug the horizontality of its site, a topography that is both harsh yet serene. Its thick walls jut out of the ground and define its boundaries.

More width than height

The inside of the mosque is equally rugged: natural stone is used for almost all its interior surface that stretch, covered by a six-meter wide concrete canopy that mimics the mild slopes of the exterior landscape, a vastness achieved with the modern technology of reinforced concrete that has outgrown the need for a vaulted structural system. Here, there is more width than height.

The wide interior worship spaces are defined by filtered light weaving through the passages of its layered entrance hallway, and a sliver of light coming down the opposite wall, on what would otherwise be known as the “mihrab,” indicative of the direction one must face while in prayer. There are no vaults, nor minarets. Not even the crescent moon.

The lone beacon of the mosque’s presence is a rectangular tower that lights at night. The light at the top whispers of its existence, almost like the crescent moon of the great Islamic domes. The Sancaklar Mosque manages to be a modest and quiet symbol of religious worship in times of modernity, reminding us that despite the need for symbolism, structures must be built to be true to their essence.

Contact the author through designdimensions@abi.ph or through our Asuncion Berenguer Facebook account.