Pangasinan town claims ‘sweetest’ watermelons

BANI, Pangasinan–The next time ripe watermelons grown here hit fruit stands, these will be labeled authentic Bani products or, at least, accompanied by certificates showing that these came from this western town in Pangasinan province.

The second-class town (annual income: P45 million-P55 million) boasts of producing one of the country’s sweetest, reddest and juiciest watermelons.

Municipal agriculturist Daniel Dacayanan attributes the distinct sweetness to the farmers’ use of saline water to irrigate the plants, and the juiciness to alluvial soil.

Sugary grains

“This is our advantage being in a coastal area. The water we use for the plants is saline. If you look at the flesh of the watermelons, you will find sugary grains, especially in their core,” Dacayanan said.

Mayor Gwen Yamamoto initiated the branding of locally produced watermelons after she noted that many vendors had taken advantage of their popularity, claiming that these came from Bani, but were actually grown elsewhere.

“Anywhere you go in Pangasinan, and even outside the province, you will see watermelons displayed with the sign, ‘Bani pakwan (watermelon),’” Yamamoto said. “We have to protect our product and also our farmers.”

How to go about branding the product was, at first, tricky for officials, traders and farmers.

Certificates

A suggestion, Yamamoto said, was to attach a sticker to each watermelon.

This was shot down because stickers could easily be copied.

“Someone also suggested the use of branding iron, like the one used in marking cattle. But again, it can be easily copied,î the mayor said. ìSo we have settled with the issuance of certificates to buyers, authenticating the watermelons.”

The certificates, however, will be issued only to buyers that the municipal government will accredit.

“Right now, anybody can come here and buy watermelons. But the problem is that some buyers do not pay the farmers in full,” Yamamoto said.

Two years ago, she said, a farmer lost money when a buyer paid him a down payment of only P100,000 and never came back to settle the balance of P150,000.

“This is one purpose of the accreditation. We will know who the buyers are and where to find them. We can run after them if they cheat our farmers,” she said.

During the planting season from September last year to April this year, more farmers went into watermelon growing due to the high demand.

This planting season, the area planted to watermelons had more than doubled, from 75 hectares in 2012 to more than 150 hectares in 2013.

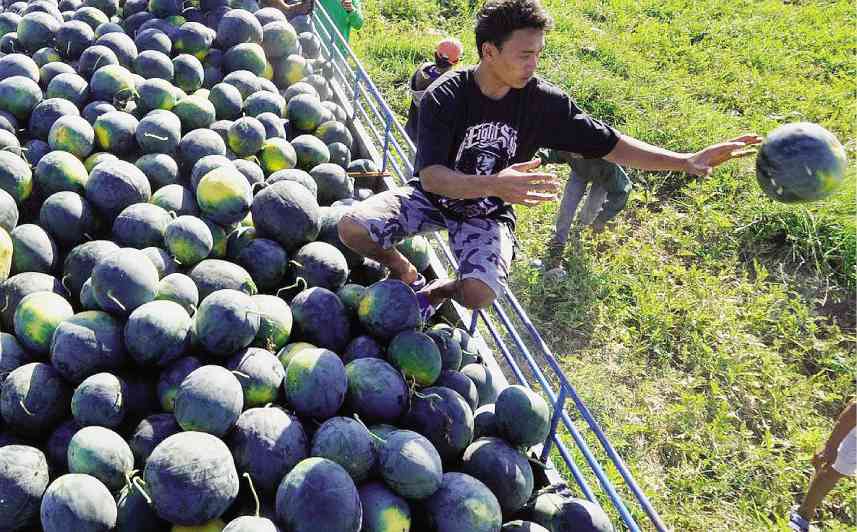

HARVESTERS load the succulent fruits on a truck. According to a town official, demand from traders has been so high that many more farmers have gone into watermelon growing.

Pakwan festival

Yamamoto said the demand had been so high, especially after the first Pakwan Festival last year.

“Traders had been coming here. So, many more of our farmers went into pakwan growing,” she said.

This year’s Pakwan Festival was held on Jan. 29 to Feb. 1. It was launched in 2013 to promote the product and to encourage more farmers to plant watermelons.

Watermelon planting begins in the upland villages of San Simon, Calabeng, Ranao, Macabit and Tiep as early as September.

It starts after the rice harvest in December in the lowland villages of Arwas, Masidem, Tugui, Luac, San Miguel and San Vicente.

Seed germination to harvest usually takes two and a half months.

Watermelon farming here began in 1986 when five farmers started planting pakwan in Barangay Banog Norte.

When they made money, other farmers followed suit.

From a capital of P75,000, they can earn from sale of watermelons up to P300,000, Yamamoto said.

Crop rotation

Until the 1990s, Bani had been earning from watermelon production when all of its lowland villages planted watermelons.

Dacayanan said about 300 hectares were planted to watermelons at that time.

But because of the changing pattern of rainfall, pests and diseases, Bani’s watermelon industry eventually nosedived, he said.

“We realized that we should not be planting watermelons continuously in the same area. There should be crop rotation,” he said.

This year, Bani has produced 620 metric tons of watermelons, compared to the 600 metric tons it yielded the previous year.

Harvest peaks from February to April.

Neighboring Alaminos City and the towns of Anda and Infanta are also growing watermelons, but they can not match the quality of watermelons produced here, Dacayanan said.