Urban transformations: The urbanization of food

(Second in a series)

Apart from news on the United States presidency and the pandemic, 2021 greeted us with some concerning local news: food prices have gone up. For instance, the price of the humble sili, a usual benchmark for food prices, was at P800 a kilo at the start of the year. Scarcity was the reported cause.

Back then, growing up in Cubao, running out of sili was unimaginable. My father was able to grow sili, kamias, coconut, guava, cheza, langka, papaya, calamansi and others in our modest yard—echoing the Bahay Kubo song. Today, most of Cubao just like many places in the metropolis are paved over, congested and built up, having no space for home farming.

Ask children today where food comes from and they are likely to answer “from the supermarket” or “from the palengke.” Urban life has disconnected people from what feeds them. The disconnection became real when food supply chains were disrupted at the start of the COVID-19 lockdowns. The geographic and functional separation between food production and the city highlights the vulnerability of our urban food system especially during times of health, economic and climate crises. One of the many ironies of our growing urban population is that we are paving over the land that feeds us.

Need for change

For the longest time, we’ve planned our cities around transportation, infrastructure, housing and recreational needs, while hoping that the rural lands around us would continue to produce food and that we could continue to transport it from farther and farther away, even outsourcing our agriculture from other continents.

If we want to plan for livable and sustainable cities, then we need to think about how our cities are fed. The increased disconnection between consumers and producers of food means that urban populations also have a limited knowledge of the issues associated with food production.

Article continues after this advertisement• Food consumption is responsible for 70 percent of the average global water footprint and 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Soil depletion, water pollution and biodiversity are all affected by what we eat. Particularly important is that as populations urbanize and become more affluent, there is an increase in meat consumption and livestock production, putting further strain on the environment.

Article continues after this advertisement• According to the Food and Nutrition Research Institute, every Filipino wastes 3.9 kilos of rice per year, equivalent to about P3.2 billion in losses annually.

• Globally, cities occupy 2 percent of total land while croplands take up 7 percent. The area consumed by livestock including the agricultural land used to feed them consume 27 percent of total global land area, more than the area occupied by forests. With increasing meat consumption brought about by increasing urbanization and affluence, livestock grazing and crop production as feed for livestock will further encroach into natural areas, putting biodiversity and natural systems at risk.

• The globalized and industrialized nature of modern food production operates on efficient economies of scale, which focus on the propagation of select species that can withstand long storage and transport (cash crops). This monoculture leads to biodiversity loss and the vulnerability of crops and livestock to disease outbreaks (such as what happened during the Potato Famine and more recently, the Swine and Avian Flu). More insidiously, global food systems have also led to less ethical approaches such as the patenting of genetically engineered plants for mass propagation, or the practice of international lending institutions to discourage farmers in developing nations to produce food for export to wealthier nations, depleting the capacity of countries to produce crops for domestic consumption.

• The UN estimates global food demand to increase by 50 percent in by 2040. More of this demand will be coming from cities—as much as 80 percent according to some estimates. As space for agriculture shrinks, climate change further aggravates the problem. Gwynne Dyer, author of Climate Wars, wrote, “The rule of thumb is that we lose about 10 percent of world food production for every rise of one degree Celsius in average global temperature.”

Reconnecting food and cities

Crises often provoke the need to reintegrate food production into the urban realm.

The planting of Victory Gardens on all available vacant properties during the two World Wars created food security and fostered solidarity and patriotism. The Organoponicos in Cuba allowed the country to be self-sufficient in fruit and vegetables, addressing food shortages after the lifeline of imports from the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989. Locally, numerous community gardens were spontaneously created in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling neighborhoods to sustain themselves during the crisis.

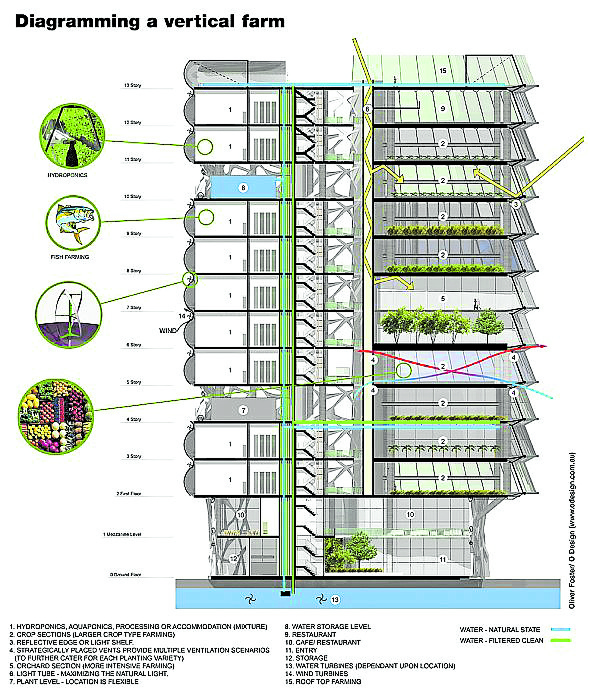

Ideas for more deliberate and intensive integration of agriculture into the urban realm vary from the pragmatic to the visionary, ranging from “Agrihoods”, Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes (CPULs) of Bohn and Viljoen, Vertical Farms by Despommier and even MRDV’s provocative concept of a Pig City: high-rises to grow livestock. Concepts of Urban Agro Ecology and Permaculture draw from the central idea that agriculture could be an essential element of sustainable urban infrastructure.

Producing food in our cities creates multiple benefits, not just in addressing food security but also as a form of ecological intensification. It is a way to conserve and replenish soils, re-establish bio-habitats and urban biodiversity, reduce and reuse food waste, conserve and reuse water, improve micro climates, clean the air, create healthier communities, and so on. Effectively, urban agriculture allows the flow of nutrients from the countryside to the city to go back to the land to grow more food, in a circular loop.

Food also has a social value: it connects people through a web of social interactions. The production of food multiplies opportunities for these interactions through the sharing or exchange of labor, inputs, and produce or in engaging the youth and the elderly in productive activity. As more rural migrants flock to cities, urban farming can offer a means of integration by offering livelihood that can immediately utilize their skill, rather than risking exclusion, malnutrition and poverty.

While urban agriculture may not yield the level of output of conventional farming, key to its value is in creating a tighter symbiosis between city and nature, blurring the artificial demarcation between urban and rural and allowing ecological systems to flourish in the urban realm.

The most influential urbanist, Jane Jacobs in The Economy of Cities wrote, “Because we are so used to thinking of farming as a rural activity, we are especially apt to overlook the fact that new kinds of farming come out of cities”.

Cities need an increased awareness of what it takes to sustain life and make space for it. Urban realms need to become what the French sociologist Michel Foucault called heterotopias–places that embrace every aspect of human existence simultaneously, capable of juxtaposing in a single space several aspects of life. A mosaic of elements both rural and urban. In a future full of cities, we need more farmers, not fewer.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a masterplanning and development consultancy firm. Visited www.jlpdstudio.com