Making room for the ‘inabel’

TO CONSISTENTLY carry out the intended pattern, a weaver’s hands must insert the weft under and over the threads with precision.

The old woman finished her blanket in three months. Being in the winter of her time, no one knows how many more blankets she will be able to weave. Her children don’t weave, they work the farm, or have their jobs in Manila, which pay them more than the weaving can. The local art of weaving is slowly dying, and the North’s abel iloko is no exception.

With many imports of fabric from India and China, the market for this craft has little demand and the lack of a future makes it an unattractive “profession.” One day, the old woman will go, and with her, the craft of making the blankets.

In last week’s “Manila Fame International” show and trade fair, a stall labeled Habi (“weave” in Filipino) showcased the different local fabrics and displayed them in their various applications. On one end were stacks of folded inabel blankets.

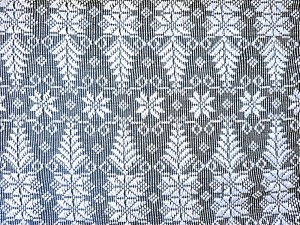

Having an Ilokana for a grandmother, the linen closets of my youth were always filled with white abel iloko blankets that relatives took down from Isabela when they visited. We had the heavy white ones, but also saw from other relatives the assorted patterns that decorate the fabrics: plaids of different sizes, floral patterns, zigzags similar to “ikat” patterns, pineapple, grape and even animal patterns. They had different weights and thicknesses too: some were almost like gauzed mosquito net; others were in heavy brocade-like textures.

Raising awareness

Article continues after this advertisementThe blankets went missing from my sphere of consciousness, (especially as my grandmother had passed away many years ago) until a few years back when they became visible in local fashion magazines. The Museo Ilocos Norte launched a project to raise awareness for these textiles in its continuous attempts to keep the craft and the knowledge of weaving alive. A fashion show brought the fabric into the mainstream, and took it as well to high art. The inabel was going to be alive and well again.

Article continues after this advertisementBut its struggles are not over. Like other locally woven material, it is trying to find appreciation among the Filipinos as an artistic craft instead of recognition as a functional item. Placed in a sea of machine-made blankets, the inabel’s price points must be understood: they arise from the unwavering determination of the hands of a weaver, throwing her threaded shuttle across her loom day after day, thread after thread, until it is woven into fabric.

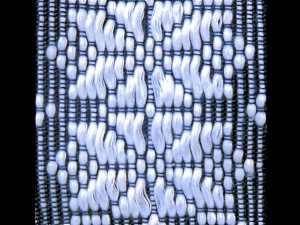

Unlike a machine, the weaver’s hands are not preprogrammed and must execute the utmost precision in threading in their fibers. Aside from having to slam the pedals of their looms with consistent pressure, they also have to ensure that the inserted weft roll in and out of the threads with precision, to consistently carry out the intended pattern. With the same material, pattern and thread color, the feel and look of the final fabric will be unique to its weaver.

The tinalak or “t’nalak” fabric of the T’boli tribe faces a similar fate. By the shores of the picturesque Lake Sebu in South Cotabato, the art of weaving this fabric spun from the fibers of the abaca is almost dead. A visit to their lakeside village revealed a few rolls of fabric, and one or two elderly women who knew how to weave it. The younger generation, had better, or shall we say, more profitable, things to do.

Without a demand, the production will struggle. Fortunately, appreciation for our local crafts has not died just yet, but needs to be escalated into a larger scale of production so that other issues relating to fabrication be resolved.

The farming of cotton—a thriving industry in the North during the colonial times when the inabel was exported—has practically stopped, and has prompted weavers to use imported threads for their blankets. How do we stake claim to a finely crafted, 100 percent, Philippine-made product when its fibers come from China? In the arena of the “finely crafted,” we are up against the Indian cottons, Thai and Chinese silks, and the other ikats of the world. There’s a lot of work to be done.

A good way

The Museo Ilocos Norte is trying to bring the inabel as a mainstream interior element by having weavers produce designs that are traditional, yet re-styled for contemporary tastes. It’s a good way to assimilate the centuries-old handmade tradition into the era of mass-spun microfibers and tech fabrics.

I left the “Manila Fame International” show in good spirits. In tow, the king-size inabel I’ve searched for and found: with a blackish indigo background and white graphic patterns, it suits my bed and the rest of my home perfectly. Once in a while I will be reminded of the old woman behind the loom. Hopefully, her daughter would have learned her craft before she moves on, like all grandmothers do.

An inabel is woven from the unwavering determination of the hands of a weaver, throwing her threaded shuttle across her loom day after day, thread after thread, until it is woven into fabric. Some blankets take several months to weave.

Contact the author through [email protected] or through our Asuncion Berenguer Facebook account.