Universal healthcare program a powerful social equalizer

Coincidentally, 100 million people worldwide are thrust into poverty yearly because of soaring medical bills. For the World Health Organization (WHO), the reason is there is no state mechanism to help these people.

It is this unfortunate statistic that universal healthcare (UHC) wants to address so people can get all the medical attention they need without fear of economic short-circuit.

UHC is “a powerful social equalizer,” WHO director general Margaret Chan popularly said. It would provide services regardless of social class, and is thus “the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer.”

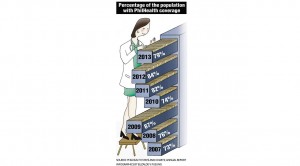

The local effort is through PhilHealth, which does not mince words with its UHC target. In the past seven years, it covered not less than 73 percent of the country’s population, far from 38 percent in 2000.

The UHC is a “noble aspiration,” David Grainger, director for global public policy of Eli Lilly and Co., told Inquirer Science/Health. He was in Manila to join global healthcare stakeholders convening for the Asia Health Technology Assessment (HTA) policy forum last July 10-11.

Article continues after this advertisementHTA is an umbrella term for research evaluating the state and societal impacts of health technologies—medicines, medical devices and procedures. The gathering discussed how results from one country can apply to another.

Article continues after this advertisement“The WHO is saying you need HTA to figure out how to expand benefit packages,” Grainger said. He sits on the board of coorganizer HTA International, a network of professionals championing HTA.

He noted “a whole spectrum of countries that embraced that concept,” but admitted that a perfect UHC score could take time. In the meantime, however, HTA principles can fine-tune healthcare to maximize its relevance to its membership.

Data

“How many people have the condition? How well are they managed? How many are receiving what sort of treatments?” Grainger said. “You need those data to understand the problem.”

According to the “World Health Report 2013,” UHC can be evaluated via who the program covers (population), what interventions it covers (services) and how much it covers (costs). UHC can be felt, however limited the resources, if countries build around common diseases, Grainger told the Inquirer.

The country did that in the past years, addressing 90 percent of the identified common diseases here. In 2011, the PhilHealth standardized the value of treatments for familiar cases like dengue and pneumonia in accredited hospitals.

“It holds the system back if you don’t have good health statistics,” Grainger said. Research can even go beyond prevalence, and analyze risk factors and multifaceted approaches to decrease incidence.

He cited the World Bank’s troubleshooting of cervical cancer in Ghana. Citizens were educated, the medical workforce trained, and screenings and vaccinations done.

“The concept there is around identifying some of the big problems and taking a holistic approach,” he added.

Manpower

Data gathering requires expertise. “It needs a lot of skilled workers—epidemiologists, pharmacologists, clinical experts, in some countries economists [because] cost-effectiveness is part of the process,” Grainger said.

Research cannot be shrugged off even by developing economies, the 2013 report said. While only Canada and a few others can afford drug testing; Nigeria, Sri Lanka and the Philippines can afford to “identify priority projects … and cascade them down through the system.” For UHC here, for example, manpower can be supplied to data production in the informal and overseas sectors.

But are there enough specialists on tap? Among UHC’s concerns is a motivated and accessible herd of health workers, the 2013 health report said. However, a 2011 WHO review said this aspect has yet to be addressed.

Citing a 2008 Factbook by the Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Association of the Philippines, the report said the government cannot create enough positions and infrastructure or distribute health workers evenly—medical professionals have more presence in Metro Manila, Central Luzon and Calabarzon than elsewhere.

Moreover, the experts migrate to other countries for financial and professional opportunities, thus 30,000 doctors are needed for the country to get to the ideal 1:1,000 doctor-patient ratio.

How much HTA findings can go cross-border? “It depends,” Grainger said, explaining that the health sector’s preparedness (e.g. Are resources enough?) and the universality of findings (e.g. Is a technology not rejected by a considerable demographic?) affect outcomes.

Nevertheless, he said HTA encourages wise policy-making, expressing approval of PhilHealth’s effort to use it—the agency now seeks partnerships with sectors like the academe—and says HTA outputs will guide package-creation.

There’s one other factor, though, Grainger cautioned. While HTA spots opportunities for growth in what UHC offers, “the next part is on-the-ground delivery, which HTA doesn’t necessarily solve.”