Corporate candor

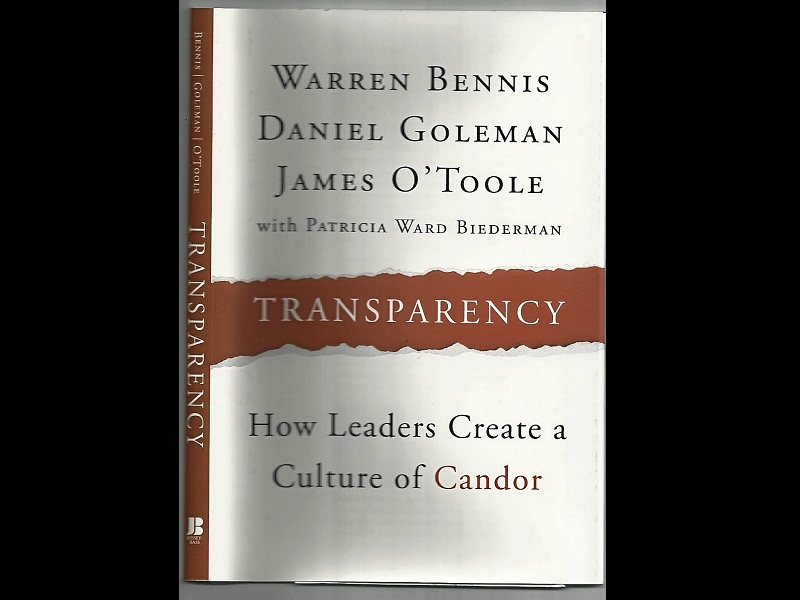

By Warren Bennis, Daniel Goleman and James O’Toole

Published by Jossey-Bass, 2008

Only a few days ago, 11 members in the Cabinet of President Benigno Aquino signed the Integrity Pledge, with this vow: “To maintain transparent and appropriate financial reporting mechanisms,” among other things. The National PR Congress will focus on “transparency in communication,” and will highlight the Integrity Initiative of Journalist Che-che Lazaro.

Do we know enough of the new mantra called “transparency”? And while we are asking this question, the “Freedom of Information” bill is supposed to be bolstered by Presidential support.

A light and handy book— with heavyweights in leadership and management studies —is perched comfortably in any major bookstore, with a title that introduces a new buzz word—“culture of candor.” The full title is: “Transparency: How Leaders Create a Culture of Candor. The authors are known for groundbreaking ideas: Warren Bennis, Daniel Goleman and James O’Toole.

The book is tidily divided into three major sections: Creating a Culture of Candor, which was jointly written by Bennis, Goleman and Patricia Ward Biederman; Speaking Truth to Power, by O’Toole; and the New Transparency, by Bennis. It is a thin book of 130 pages, and yet every paragraph is packed with insights, research data, narrative of events to illustrate a point, and even a journey to antiquity as far back as 2,500 years ago—to show that man hasn’t changed; only technology is fast changing.

Immediately, the book advances a caveat: “Complete transparency is not possible.” The book cites that court records could not possibly reveal the details of a case, especially witnesses whose lives would be at risk.

And yet the book cites a compelling reason for organizational candor: it maximizes the probability of success.

George Washington is known for demanding unbiased information. He solicited intelligence from as many people as possible, even civilians, before going into battle. “He had an intuitive grasp of the dangers of the “shimmer effect.” The authors say, the “shimmer effect” confers god-like qualities to leaders and ascribe to them infallibility. Shades of the Pope’s infallibility!

A myth has even persisted in management practices that include this advice: “It is better to make a bad decision than making no decision at all.”

The authors recall the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1962, when the late President Kennedy ordered an invasion of Cuba based on intelligence data that were not validated beyond the supposed experts. The US military and the State Department assured Kennedy of an armed underground of Cubans would rise against Castro. They did not tell him that a year-ago poll that showed majority of Cubans still supported Cuban strongman Fidel Castro.

So, how does one evolve a culture of candor in an organization, despite hard-to-break values of hoarding or hiding information?

The authors say it must begin with the CEO. “Leadership must show that speaking up is not just safe but mandatory.” It must be a policy to hear critical information, whoever delivers it—because, if we don’t, it may put the entire enterprise at risk.”

Transparency has given birth to new industries or research projects.

For example, Joel Kurtzman who developed a transparency measure called the “Opacity Index.” Opacity, which is the lack of transparency, can indeed be measured.

The book points out that, in the most recent Opacity Index, the United Kingdom topped the transparency index, followed by Finland, Hongkong and the United States came fourth. The least transparent were Nigeria, Lebanon, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia. The book did not mention if the Philippines was included in the research.

Another enterprising move was the development of the Whistleblower Software, offered by EthicsPoint and Global Compliance Services. This software allows employees to anonymously report to management any suggestions or case of wrongdoing.

And yet some corporate values frustrate transparency, while encouraging, opacity. The authors said the tradition of “family secrets” have been brought to the boardroom in the form of company secrets— which discourage transparency.

They also identified “group think” as another barrier to corporate candor. Decisions are made by the top leaders, and are not shared downwards. Their research showed that the higher the leaders rise, the less honest feedback they get from followers about their leadership, due to this group think of limiting information sharing with the old boys network.

Lack of candor can be very disastrous. The book recalls the ill-fated Challenger which exploded in mid-air in 1987. Nasa did not learn its lesson: In 2003, there was the Columbia shuttle disaster. The authors lament Nasa’s organizational culture where engineers were afraid to raise safety concerns with managers who were more worried about meeting flight schedules.

The book is convincing when it prescribes ways to nurturing the culture of candor. Transparency is enhanced when an organization’s leaders are committed to it.

Actually, the authors cited a sobering fact: “Even when leaders resist it, transparency is inescapable in the digital age.”

Google has it impossible for any candidate to deny past actions or statements. YouTube has changed America’s political discourse.

In this idea-packed book, leaders and managers will have a roadmap toward transparency—or culture of candor. They speak of three elements to achieve this: Transparency, trust, and speaking truth to power.

“Speaking truth to power” is a new phrase in our leadership vocabulary. It means speaking the truth to your superior even if he is wont to shoot the messenger—meaning, you.

The devotees of candor should not be perturbed. The leaders who signed the Integrity Pact may want to go further and heed the advice of the three leadership gurus: Provide equal access to information to all, refrain from punishing those who constructively demonstrate imperial nakedness (remember the Emperor with no clothes?), refrain from rewarding spurious loyalty, and empower and reward principled contrarians.

The book introduces new words—necessarily so, because they are giving birth to a new leadership style. The contrarian is one who contradicts no matter of what. But they also advise that you should not be given to anger; don’t burn your bridges. The contrarians will take comfort in the fact that “we have a moral obligation to speak truth to power.”

The lack of privacy is perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the new transparency. “We are all public figures now,” said Thomas Friedman. The downside of transparency is we now live in glass houses.

The authors dish out this advice: “With the digital age’s millions of intrusive cameras, its constant potential for trumpeting past indiscretions through cyberspace, the new reality will force us to adapt or go mad. Since the cameras aren’t going away anytime soon, we’ll have to find a way to lower the blinds in our glass houses, if inly in our minds.”

Better still, folks, lower the curtains, once you have bought this book. It will give you a wealth of insights and contexts that will make you an informed devotee of corporate transparency—or candor.