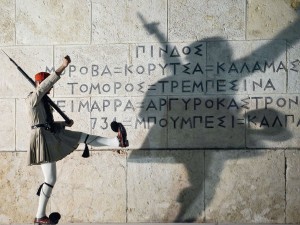

CHANGING OF GUARD A night before election day, a Greek Presidential Evzoni guard prepares for a changing of the guard in front of the Greek parliament in Athens. As Greece heads for a momentous electoral battle that could decide whether it stays in the euro zone, party leaders are scrambling to reassure angry voters they can bank on the single currency. AFP

Greeks will have to wrestle with a crucial dilemma when they go to the polls for the second time in as many months on June 17 to elect a new government.

The outcome could determine whether Greece sticks with the heavy budget cutting that is required under the terms of an international bailout—or rejects the harsh austerity measures imposed by the rest of Europe.

If Greeks choose the latter, they risk expulsion from the euro, which would likely induce more pain on an economy already in its fifth year of recession.

The uncertainty in Greece has been hanging over global financial markets for months, and analysts say Sunday’s election may not lead to a quick resolution.

But the election will help determine whether the financial crisis that has plagued Europe for more than two years is slowly coming under control—or about to get much worse.

Here are some questions and answers on the Greek election and why it matters to the rest of the world:

Why is Greece back in the news?

In a nutshell, the June 17 vote is being seen as a referendum on the euro.

Greece secured in March a second multibillion-euro rescue package consisting of loans and debt restructuring. This bailout came with more tough austerity measures, such as cuts in public sector pay and pensions that the country is struggling to meet.

The spending cuts have left the economy mired in a deep recession. Angered by the seemingly endless pain, Greeks turned away from the two traditional parties—conservative New Democracy and socialist Pasok—in elections last month. They voted instead for more radical parties that have vowed to pull the country out of its bailout and austerity agreements.

But if the country renounces its bailout terms, Greece’s international partners could stop providing the rescue loans on which the country depends.

That could lead it to default and force it out of the eurozone—a move that could greatly weaken the euro and send shock waves across the global financial system.

What would happen to Greece if it left the euro?

No country has ever left and there are no procedures in the European Union’s vast rule book for pushing any country out. But if Greece left the euro, it would then have no choice but to start printing its own currency—the drachma—to pay its way.

Such a move would hit the Greek people hard—and quickly, according to the Greek think tank Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research. The new drachma would lose half or more of its value relative to the euro.

This would drive up inflation and sap the purchasing power of the average Greek. At the same time, the country’s economic output would drop, putting more people out of work where one in five is already unemployed. The prices of imported goods would skyrocket, putting them out of reach for many.

However, there are some analysts who say a weaker drachma would make Greek exports cheaper and more competitive and could help the economy start growing again.

Companies outside Greece might be attracted by the cheaper labor and real estate, encouraging them to move manufacturing plants there. Tourism might also get a boost: booking a hotel room on a Greek island, for example, would suddenly become much cheaper for foreigners.

Greece is such a small economy. Why does its membership in the euro matter?

True, Greece’s economy makes up about 2 percent of the euro zone’s overall economic output. But if Greece falls out of the euro zone, investors will become nervous about whether other financially shaky countries, such as Italy, could also leave.

That fear would likely drive up borrowing costs for these and other countries, potentially to levels that would require them to seek international bailouts. Europe would be trapped in a vicious circle.

The European banks that hold much of the continent’s government bonds would become significantly weaker and more reluctant to lend to one another. This could spark off a credit crunch like the one that followed the collapse of US investment bank Lehman Brothers.

This problem could be made even worse by savers and investors taking money out of banks in shaky economies and moving it out to safer countries such as Germany or even out of the euro zone altogether. This could further destabilize the banking system.

What could happen on June 17?

Market watchers and other European politicians are worried that Syriza, which came second in the May election on an antibailout ticket, might do better this time around. Alexis Tsipras, the party’s charismatic leader, has vowed to cancel Greece’s international bailout agreement if he wins.

Both Pasok and New Democracy have vowed to try to renegotiate parts of the bailout in an effort to stimulate Greece’s moribund economy. However, they do not advocate pulling the plug on the deal and insist the top priority is to keep Greece in the euro—something that 80 percent of Greeks want.

To form a government, the winning party—or coalition—needs to hold a minimum of 151 of Parliament’s 300 seats. Whichever party comes first will get a bonus of 50 seats in Parliament under the Greek electoral law. Still, it is highly unlikely that any party will win enough seats for an outright majority—meaning there will be another round of negotiations to form a governing coalition.

But apart from Greece, the euro zone is back on track, right?

Hardly. Spain has become the latest—and largest—country in the eurozone to ask for a bailout. The country’s borrowing costs have shot up over the past weeks on concerns that it does not have the money to prop up its troubled banking sector, which has been crippled by a collapse in Spain’s property market.

On Saturday, the Spanish government acknowledged it would seek outside assistance for its banks after the eurogroup—finance ministers from the 17 euro countries—agreed to offer Spain 100 billion euros in bailout loans. Spain will decide how much it needs once independent audits of the country’s banks have been completed.

The bailout move was meant to calm markets ahead of the Greek elections. Instead it has had the opposite effect.

Worried about the extra load on Spain’s debt the bailout loan would have, markets have fought shy of Spain all week, sending its borrowing costs to the highest level since the country joined the euro in 1999.

These jitters have been also felt in Italy, which is struggling to maintain its huge debts as its economy falters. Italy also saw its borrowing costs rise this week when it went to the markets to sell its debt. AP