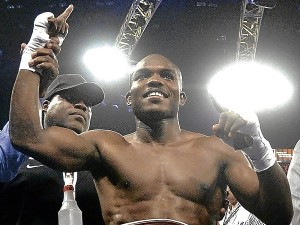

As surprising as Timothy Bradley’s split-decision win over Filipino boxing champ Manny Pacquiao is, the former’s vegan diet (devoid of any animal protein—pork, beef, chicken and dairy) during training isn’t really new in the athletic world.

Nine-time Olympic gold medal winner and vegan Carl Lewis, who was voted “Sportsman of the Century” by the International Olympic Committee and named “Olympian of the Century” by the American Sports magazine Sports Illustrated, was quoted in chef Jannequin Bennett’s book “Very Vegetarian” that his best year of track competition was the first year he was on a vegan diet. “Moreover, by continuing to eat a vegan diet, my weight is under control, I like the way I look,” he said in the book’s introduction.

World champion athletes who are known vegetarians, as compiled by “The Food Revolution” author John Robbins from various nutrition experts including Suzanne Havala’s “The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Being Vegetarian,” Anika Avery-Grant’s “The Vegetarian Female” and Lisa Dorfman’s “The Vegetarian Sports Nutrition Guide” are Ridgely Abele, winner of eight national championships in karate; Surya Bonaly, olympic figure skating champion; Peter Burwash, Davis Cup winner and professional tennis star; Andreas Cahling, Swedish champion bodybuilder, Olympic gold medalist in the ski jump; Chris Campbell, Olympic wrestling champion; Nicky Cole, first woman to walk to North Pole; Ruth Heidrich, six-time Ironwoman, US track and field Master’s champion; Keith Holmes, world-champion middleweight boxer; and Dave Scott, six-time winner of the Ironman triathlon. The list goes on.

Sports nutrition

Nutritionist and book author Sally Beare once said a typical 800-pound adult male gorilla thrives on a vegan diet of vegetables, fruit and nuts. “True, the gorilla is only a close relative of ours, but the latest research in sports nutrition shows that our top athletes not only build sufficient muscle, but do best in terms of endurance and stamina, when following a vegetarian diet.”

Yale University professor Russell Chittenden, in the early 1900s, was one of the first to challenge the great meat protein myth. He conducted at least three studies that examined the question of whether meat and high protein were really necessary for optimal performance.

Dr. Neil Nedley, author of “Proof Positive,” said the capstone of Chittenden’s research was a study of well-trained athletes.

“At the beginning of his study, these athletes were all on a typical meat diet. Chittenden had them then switch to a plant-based diet for five months. At the end of the study period when their fitness levels were reanalyzed, the athletes had improved a striking 35 percent.” As Dr. T. Collin Campbell, professor emeritus of Nutritional Biochemistry at Cornell University once interviewed by Inquirer Science and Health, commented: “only the dietary change could have accounted for these remarkable results.” Campbell discusses this in his article “Muscling Out the Meat Myth.”

“What Chittenden suggested years ago is now being re-echoed by hundreds of voices. Eating animal flesh and animal protein is not necessary in order to obtain optimal protein intake for productivity and performance,” Nedley said.

The American Dietetic Association put it succinctly when it said in 1988: “It is the position of the American Dietetic Association that vegetarian diets are healthful and nutritionally adequate when appropriately planned.”