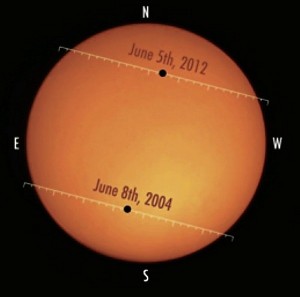

IN THIS Nasa photo, Venus appeared in silhouette as a small, dark dot moving in front of the solar disk. Since the event occurred across the International Date Line, the transit of Venus happened on Tuesday, June 5 in North America or Wednesday June 6 in Asia and Australia

The last chance most of us will ever have to see the planet Venus pass in front of the sun happened this week.

Such an astronomical spectacle is among the rarest. The only eight transits of Venus to have been observed by humans since the invention of the telescope occurred in 1631, 1639, 1761, 1769, 1874, 1882 and most recently in 2004.

As one may have guessed, the transits of the second planet from the sun, are visible from Earth in pairs separated by eight years due to the peculiarities of the orbits of the planets around the sun. Last Wednesday’s transit is the second in a pair that began with one in 2004, which at the time was the first visible in more than 122 years.

Before 2004, the last pair of transits happened in December 1874 and December 1882. The next transit of Venus won’t occur until Dec. 10 or 11, 2117.

The Venus transit this week took a west-to-east passage (right to left direction) that took six hours and 40 minutes. The Philippines was lucky enough to witness the entire crossing, which occurred from 6:09 a.m. to 12:49 p.m.

“It’s a must-see event for skywatchers as Venus won’t cross across the solar disk again for 105 years,” said James Kevin Ty of the Astronomical League of the Philippines.

The moments when Venus first appears to cross the limb (edge of sun’s disk) of the sun and the moments it leaves are historically the most scientifically important aspects of the transit since comparison of Venus’ journey viewed from different points on Earth provided one of the earliest ways to determine the distance between Earth and the sun.

Measure distance

In the early 18th century, Edmund Halley (after whom the famous comet is now named) determined a way to measure the distance from the Earth to the Sun by precisely timing the transit of Venus from widely separated parts of the Earth. According to him, once this distance was known, the distances to other planets could be determined through Kepler’s Laws.

One of the reasons so many scientists in the 1700s and 1800s voyaged thousands of kilometers from home was to observe it. Among them was the team of British explorer James Cook who went to the south Pacific island of Tahiti to witness the event and take measurements (and afterward, sailed on to claim Australia for England).

Interestingly, astronomers used Cook’s measurements to calculate a distance to the Earth of 150 million kilometers, close to the now-accepted value of 149,597,870.7 km.

This time around, scientists will no longer be measuring distance. They would however, verify techniques. As Venus transits the sun, sunlight will be filtered through the planet’s atmosphere, an occurrence, which would enable today’s Earth-based scientists to learn more about the chemical elements present in the gaseous haze around Venus.

This is why a number of the world’s premier telescopes trained on the sight, including National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Hubble Space Telescope and Solar Dynamics Observatory. The European Space Agency’s Venus Express satellite, which is currently in orbit around Venus, would be used to validate the accuracy of the tests.