With food security as one of the key governance concerns, urban planners need to understand the dynamics between the food distribution chain and the space creation process.

Food and space through time

The configuration of living spaces has followed accordingly—from the Paleolithic period when human beings moved around for nourishment to the present times when people engage in global networks to thrive.

In the interest of survival and longevity, place production has been guided by the goal of accessing resources at the very least.

Pursuit of efficiency, security

Over the years, the increasing complexity of social organizations has prodded the pursuit of efficiency and long-term existential security (Cisterna, 2013).

The age of industrialization highlighted the urban-rural dualism where subsistence food production was relegated to the agricultural zones outside of the city.

Urbanization was fueled by mass processing through assembly line systems that were hosted in the cities (Potts, 2021). Processed food found their way to public markets and groceries—the distribution hubs around which residential areas developed.

The age of globalization saw the proliferation of food chains that promoted standardized products and services while catering to local labor and market realities. The global production network also blurs urban-rural dependency as cross-border exchanges respond to cost-efficiency goals (Dey, 2007).

The post COVID-19 pandemic food production and supply setup is marked by online selling and computer application-aided delivery systems. The continuously evolving virtual spaces account for obsolete and redundant spaces but also instigate innovation in food-related space creation.

Food industry agglomeration

The “restaurant streets” trend—seen in the examples of Maginhawa Street in Quezon City, Friendship Highway in Pampanga and Tanay biker’s strip in Rizal—are all manifestations of the local agglomeration process.

Food-related businesses of varying scales converge in one geographic space and benefit from proximity to each other (Schmit, Hall, 2013). These food streets are enmeshed in larger networks that include anchor areas such as universities, offices, resorts and tourism destinations. As a collective, these networks thrive and grow based on interdependent relationships.

Cities as agglomerative entities also typically grow because of these industry-based spatial concentrations. These trends alter urban space organization as land uses change and as places gentrify. Changing land uses may have positive and negative effects on the communities where new food businesses land.

City branding, food-based specialization

The association between cities and their gastronomic economies can become stronger over time as the host spaces expand through enabling local government policies.

Many cities all over the world have tapped on their food products for branding and promotion. The kakanin spaces of Cainta remain as distinctive elements of the city even while shopping malls emerged in and around their administrative bounds.

From family and community-based enterprises to large production factories, specialty food industries direct urban space configuration that account for place recall. The sight, smell, sound, and kinesthetics of food spaces become part of the city’s defining qualities (Dürrschmid, 2011).

Enhancing tourism

The food-place association also enhances the tourism sector as indicated by the Lindt chocolate factory tours in Switzerland, the wine and cheese tasting tours in Tuscany, the sili ice cream in Albay, and the culinary tours in Iloilo.

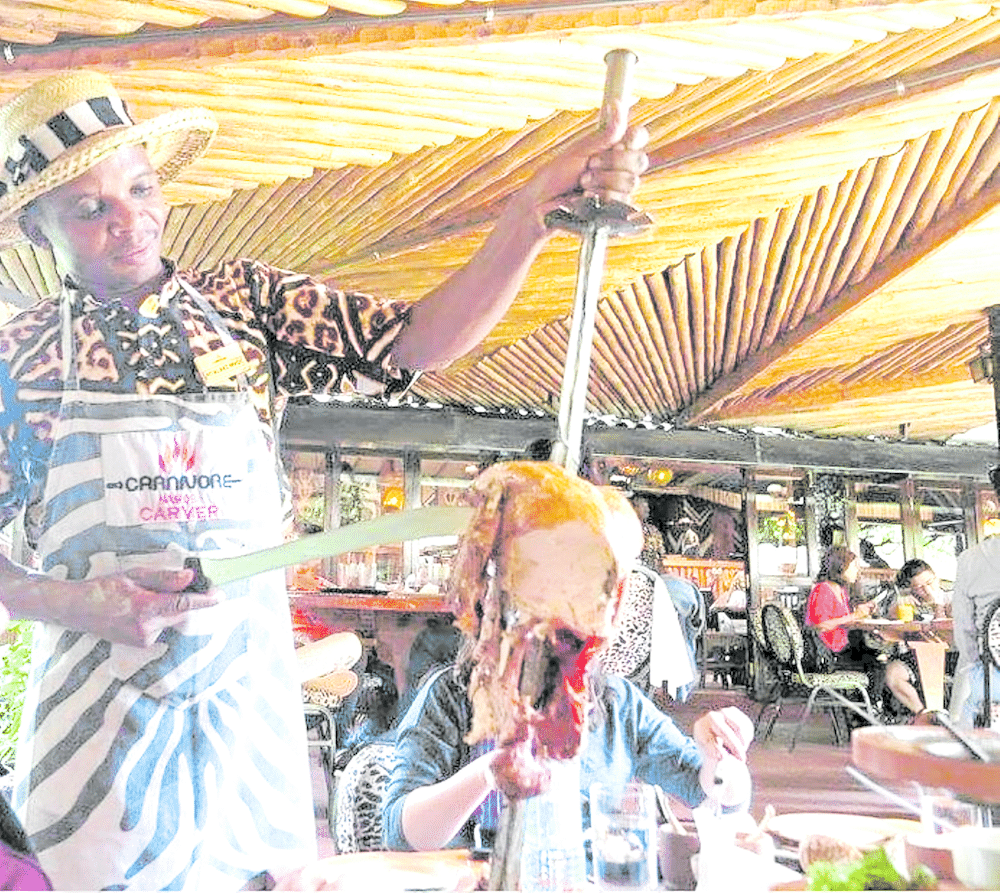

Some heritage houses in the Philippines are reused as restaurants and event places. Food cultures such as the aperitivo in Italy, the guinea pig festival in Peru, and the communal kimchi making in Korea strongly underlie space creation in these countries.

Design translations

In recent years, we have witnessed the emergence of design concepts that either respond to or instigate new food-city relationships.

Urban farming—as a strategy aimed at augmenting food supply in crowded cities—has translated into design typologies such as vertical farms, farm lot subdivisions, and integrated agri-residential developments. The green movement found expression in green walls and home-based production through the aquaphonic and hydrophonic systems.

The growing strength of the sustainable practices advocacies has figured significantly in the waste management systems of the food industries in the city.

The concern over farmers’ livelihoods translated to farm-to-table restaurants that seek to ensure freshness of food ingredients while addressing the distance and transportation cost issues that beset farmers. The cultural convergences brought about by globalization are seen in the fusion concept that reflects both in the dishes served and the architectural characters of dining places.

Filipinos, being very communal, will continue to patronize events places and the food catering businesses that go with them. Food as basis and shape giver of culture will always be one of the important urban development factors.

References:

Cisterna, N.S. (2013). Food and Place. In: Thompson, P., Kaplan, D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6167-4_18-3

Dey, S. (2007). Globalization and its Real Benefits. Critical Perspectives on International Business.

Dürrschmid, K. (2011). Food and the City. https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/256492865_Food_and_the_City

Potts, D. (2021). Reshaping the Urban-Rural Divide in the 21st Century: Shifts in the Geographies of Urban-Based Livelihoods. Global Urbanization: Nations, Cities, and Communities in Transformation. 74/1 Fall/Winter 2021.

Schmit, T. & Hall, J. (2013). Implications of Agglomeration Economies and Market Access for Firm Growth in Food Manufacturing. Agribusiness International Journal. 29/3, 306-324. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21336

The author is a professor at the University of the Philippines College of Architecture, an architect, and an urban planner