Dreaming of an alternative building future

We take a sigh of relief that the Habagat season is almost over. The extreme weather we’ve been experiencing will now transition to the (hopefully) milder Amihan season.

The recent weather events provoke some pondering on how much worse climate will be in the coming years. It is said that humanity is caught amid two opposing forces: the pursuit of economic growth and the need to protect our depleting biosphere—forces that are ironically diametric yet causal in their relationship.

While there have been valiant efforts to address climate change, global carbon emissions continue to rise despite the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015.

As the world scratches its head on how to balance these two opposing needs, building industry professionals are not spared of responsibility. Buildings still account for 40 percent of annual global energy-related carbon emissions (15 Gigatons of Carbon per year).

Co-evolution

Why haven’t we evolved a built environment to a form that is more congruent with nature’s biological systems?

Co-evolution would’ve made sense since natural systems preceded humanity for millions of years, evolving into a highly resilient and adaptive complex system—giving rise to complex biological forms (humans), who in turn, gave rise to complex forms of organization (culture).

Yet, both natural and cultural systems evolved differently, reaching their current state of mutual opposition wherein the growth of one requires the depletion of the other.

This is most evident in our cities with the unrelenting urban engulfment of natural environments—directly through sprawl or indirectly through the extraction of finite resources for consumption.

Unrestrained growth

Even though our global economic growth has long surpassed Earth’s resource generation capacity, unrestrained growth remains to be the prevailing economic paradigm.

This infinite growth model—amid the biosphere’s finite resource—is often justified by a view of Prometheanism, which perceives Earth as a resource whose sole purpose is to satisfy human needs and whose environmental problems are overcome through human innovation.

This is the philosophy behind ambitious proposals to sequester carbon from the air through “direct air capture technology”—effectively using new technology to clean the mess created by old technology.

Co-evolution of nature and culture

Can the evolutionary paths of nature and culture converge into a common trajectory where the future, borrowing from Karl Marx, “promises an eventual transcendence beyond the antithesis of humanity and nature”?

This implies creating a society that is premised on ecological awareness, or a conscious coexistence with nature rather than its subjugation. In our built environments, it will require creating cities that enable a stable metabolic exchange between human societies and the natural environment.

Green building movement

Attempts to mitigate environmental impact are laudable and the push for greener buildings has become mainstream.

The green building movement has shaped mindsets, increasing awareness and desire for more sustainable built environments. But their application remains limited and the task ahead remains daunting.

Experts estimate about 230 billion sqm of floor area need to be added to the global building stock to support Earth’s estimated population of 10 billion people by 2050. This is equivalent to constructing all of the buildings in New York City every month for the next 25 years.

Most of these new floor spaces will be built in developing nations like the Philippines, and will cater to lower-income segments of the population. Green building technologies will therefore need a broader and more affordable application to make a dent in our emissions contribution.

Beyond natural building materials

It all starts with the materials we use and our ways of energy capture.

There have been numerous efforts to use renewable materials such as timber and bamboo—important steps toward sustainable building. A few promising and exciting ideas, however, look beyond inert natural materials and toward those that are biologically alive—a true convergence of natural and built systems.

Bio-cementation

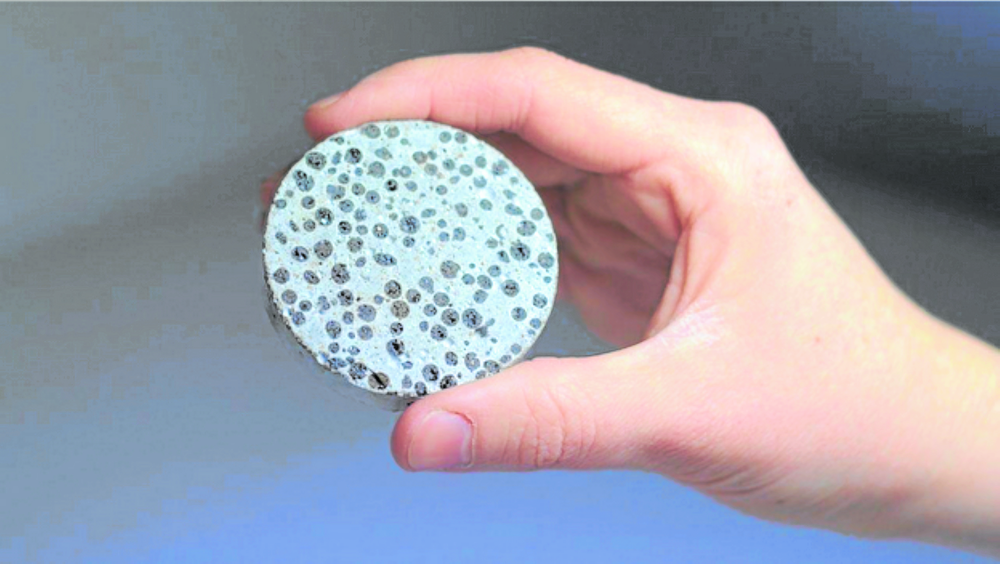

Cutting edge research experimented with living microorganisms such as cyanobacteria to create biocement, and mycelium (the fibrous root system of mushrooms) to create living bricks stronger than concrete.

The materials within these blocks continue to have biological functions and under ideal conditions, the living brick will not only heal cracks but also reproduce and grow organically into a new brick.

Microbial fuel cells

Microbial fuel cells use microorganisms to produce electricity. These microorganisms feed off and oxidize organic matter (such as waste matter), a process that releases electrons and thus produces small amounts of electric current.

Once the technology further develops, the electrical output can be scaled to produce living walls of fuel cells to power buildings. If successful, this will address two urban issues at once, treating wastewater and producing electricity from it.

Bioelectricity

This can be generated using photosynthetic microalgae, allowing them to use light (artificial or natural) to generate electrical energy.

With this technology, outdoor and indoor surfaces can culture algae and generate power for the use of the building, turning them into photovoltaic structures—the way plants harness sunlight to create their own energy.

Aspirations

Buildings that function like trees; cities that are like forests—these are the aspirations for the built environment of “Cradle to Cradle” author Michael Braungart.

Are these just pipe dreams borne out of some romantic yearning for an ideal utopia meant to give us some hope for the future? Who knows?

Only time will tell whether these nascent technologies make it to the mainstream to replace our old and corrosive technologies. We can look to the past and recall how fossil fuel was once just a nascent technology experimented on to replace the less efficient and increasingly scarce wood charcoal. This form of energy capture eventually led us to the divergent paths of nature and culture that we are presently on.

We need to dream new dreams to arrive at outcomes that are radically new, even if they seem too idealized and far-fetched. After all, planning always starts off as works of fiction.

The author is a built environment professional and the founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning, architecture and property consultancy. www.jlpdstudio.com