The city can be characterized as a cacophony dominated by anthropogenic sounds—the continuous rumbling of engines, sirens alarming everyone, the harried steps of people setting the urban pace. Such sensory stimuli in every corner of the city can overwhelm anyone.

As more than half of the world’s population now lives in urban areas, questions on the capacity of the city to provide for the holistic needs of the individual become even more pressing.

Are we actually creating livable urban spaces?

Urban stress

Urban stress affects almost everyone.

It refers to the interplay of urban contexts and how it affects the psychological state and stirs response to how people perceive the threats brought about by negative urban conditions such as pollution, density, extreme weather, noise, damaged ecosystem, loss of human capital, etc. It has been attributed to the increase of physical and mental diseases, moral decay, sense of insecurity, and lower productivity of people in cities.

Radicchi asserted that our cities have become noisier. This is confirmed by Centeno, who found that the dominant soundscape of Quezon City is composed of anthropogenic sounds even when they are measured in selected green spaces.

Noise affects even the quality of sleep one gets in the city, leading to less quality of life for many of the urban dwellers. Likewise, it has been noted to affect biodiversity and natural processes in the city.

Such realizations on the negative impact of noise have led some cities to develop quiet urban areas.

Quiet zones

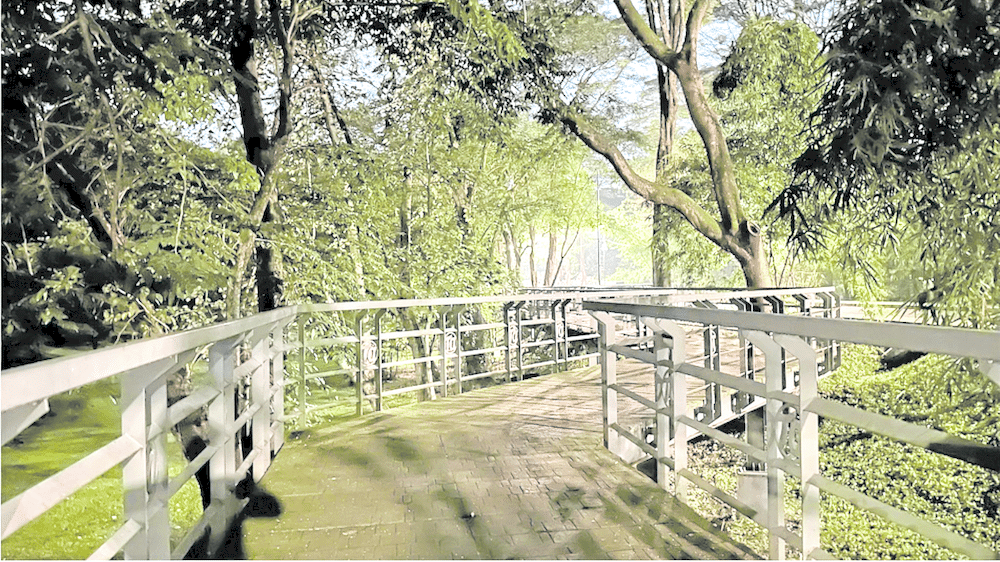

“Quiet urban areas” are public areas that can offer respite from anthropogenic noise by encouraging social interaction and communication. They serve as an accessible sanctuary from unwanted sounds using urban greenery.

Aside from serving as noise barriers, they can help filtrate air, reduce particulate matter and pollutant concentrations, and improve biodiversity, which can then help improve the soundscape of the city. The presence of natural sounds such as bird songs and breezes can help people relax and improve their concentration, and in turn their overall health, wellness and urban experience.

One characteristic of a quiet urban area is the absence of crowds.

It has become a rarity for someone in the city looking for a space that is not dominated by noise. This is observable in many cities in the Philippines where the soundscape is dominated by noise produced by urban processes, drowning out the natural sounds produced in the few remaining green spaces.

This is exacerbated by the continuous trend of fragmentation of many green spaces, many of which are found in affluent neighborhoods—isolating parks out of access of most Filipinos. No wonder Filipino workers topped the list of the most stressed workers in Southeast Asia in 2021.

Public parks should ideally serve as a refuge to experience better urban soundscapes.

However, as in the case of Quezon City, only a few remaining pockets of greens, such as the University of the Philippines campus, can be truly considered as parks. Many off such spaces have been increasingly built up with more structures, like barangay halls and covered courts, at the expense of spaces for greens and plants.

Muffled sounds

Cities can have spaces that promote introspection, allowing people to breathe in the urbanscape and take in the progress of civilization.

They should foster the well-being of the people, balancing the live-work-play dynamics of residents of various abilities and capacities, humans and non-humans alike. These inhabitants should be able to hear themselves pulsating as a living entity, allowing for a meditative state of calmness and tranquility.

References:

Alvares-Sanches, T., Osborne, P.E., White, P.R. (2024). The challenges of mapping quiet urban areas from mobile sound surveys. Inter-noise Conference.

Centeno, D. D.G. (2024). Urban Symphonies: Modelling Quezon City’s Urban Park Sonotypes through a Multi-Method Soundscape Approach. Master of Tropical Landscape Architecture Thesis, University of the Philippines-Diliman.

Dela Peña, K. (2022) Gallup poll finds PH Workers most stressed in Southeast Asia. Newsinfo.inquirer.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1621483/gallup-poll-finds-ph-workers-most-stressed-in-southeast-asia.

Jaszczak, A., Pochodyla-Ducka, E., Dreksler, B. (2023). Can Green Areas be a Noise Barrier in Cities? Analysis of Centralny Park in Olsztyn in Terms of Noise Impact and Soundscape Modeling. Teka Komisji Urbanistyki i Architektury Oddziału Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Krakowie.

DOI: 10.24425/tkuia.2023.148971.

Rahimi,l M., Behzadfar, M., Jalilisadrabad, S. (2023). Investigation of the relationship between urban stress and urban resilience. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management. 8(3): 317-332, Summer 2023.

Radicchi A. (2017). A Novel Mobile Application to Crowdsource and Access “Everyday Quiet Areas” in Cities. Invisible Places (Conference Paper)

The author is a landscape architect and Professor at the University of the Philippines Diliman College of Architecture