Stock corporations and shareholders’ rights (derivative suit)

(Second part)

A corporation is an artificial entity created by law, possessing a separate juridical personality distinct from its owners — the shareholders. Shareholders own shares of stock, which represent their ownership interests in the corporation.

Each stock corporation is governed by a Board of Directors, whose members are elected by the shareholders. Each director is required to own at least one share of stock in their name.

According to the Revised Corporation Code, the Board exercises corporate powers, oversees the conduct of business, and controls all corporate properties. (Sec. 22, Revised Corporation Code).

While certain matters must be approved by shareholders under the Revised Corporation Code, it is ultimately the Board of Directors that sets the corporation’s direction, establishes targets and goals, ensures that proper actions are taken to achieve these, and appoints officers to manage daily operations.

One of the corporate powers exercised by the Board is the power to sue and be sued. However, an exception to this general rule is the derivative suit —a legal action brought by shareholders on behalf of the corporation. (Sec. 35, Revised Corporation Code; Villamor, Jr. v.Umale, GR 172843, September 24, 2014).

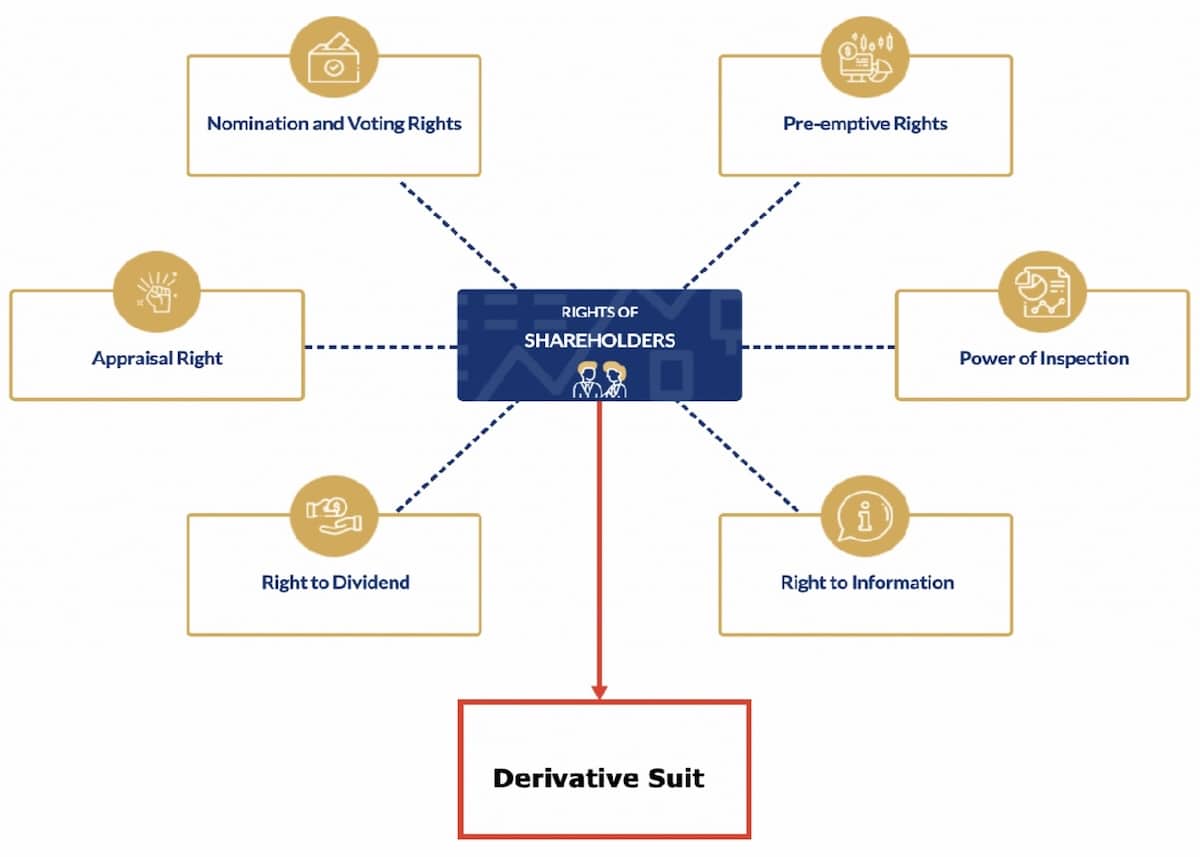

For this reason, the right to institute a derivative suit is considered one of the essential Rights of Shareholders.

A derivative suit is an action initiated by stockholders to enforce a corporate right. It is primarily brought by minority shareholders on behalf of the corporation to address wrongs committed against it, which the Board of Directors has failed or refused to address. As an equitable remedy, the derivative suit serves as a key defense for minority shareholders against potential abuses by the majority. (Western Institute of Technology, Inc., et al. v. Salas, et al., GR 113032, August 21, 1997).

While the Corporation Code and the Securities Regulation Code do not expressly provide for the stockholder’s right to file a derivative suit, it is implicitly recognized when these laws hold corporate directors or officers liable for damages caused to the corporation and its stockholders due to breaches of fiduciary duties.

In essence, a derivative suit compels the corporation to fulfill its obligations to stockholders. It serves as a protective mechanism when the corporation’s management or board refuses to act to safeguard the corporation’s rights.

The Supreme Court has laid down the requisites for filing a derivative suit, which are as follows:

a. The party suing on behalf of the corporation must have been a stockholder at the time of

the acts or transactions in question, as well as at the time the suit was filed;

b. The party must have exerted all reasonable efforts to resolve the issue within the

corporation, and this must be specifically detailed in the complaint;

c. The act or acts complained of must not have allowed for the exercise of appraisal rights;

d. The suit must not be a nuisance or harassment suit; and

e. The suit must be filed in the name of the corporation.

In a Supreme Court decision, Metrobank v. Salazar, et al., GR 218738, March 9, 2022, minority shareholders of Salazar Realty Corporation (SARC) filed a derivative suit after SARC mortgaged five properties to Metrobank to secure a loan for Tacloban RAS Corporation. When Tacloban RAS failed to repay the loan, Metrobank foreclosed on the properties, prompting the minority shareholders to file a complaint on behalf of SARC, challenging the mortgage and

auction sale.

The shareholders argued that the mortgage involved substantially all of SARC’s assets and should have been approved by the stockholders, which was not done. However, the Supreme Court ruled against the shareholders because they failed to comply with the requisites for a derivative suit, specifically: (a) they did not properly allege the exhaustion of available

remedies, including appraisal rights, and (b) they did not categorically state that the suit was not a nuisance or harassment suit.

To conclude, while a derivative suit is a fundamental Right of Shareholders and serves as an exception to the rule that corporate powers are exercised solely by the Board, proper resort to this remedy requires compliance with strict legal requisites. Failure to meet these requirements will result in the suit being denied by the courts.

* * *

The author, Atty. John Philip C. Siao, is a practicing lawyer and founding Partner of Tiongco Siao Bello & Associates Law Offices, an Arbitrator of the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission of the Philippines, and teaches law at the De La Salle University Tañada-Diokno School of Law. He may be contacted at jcs@tiongcosiaobellolaw.com. The views expressed in this article belong to the author alone.