How are cities created?

Contemporary property development relies on masterplans, which serve as the basis of how cities and townships are built.

Masterplanners produce static, end-state outcomes based on limited knowledge available to them at the time of ideation—a snapshot of a future place, shaped by how they view the world as it could be: a grand vision like Burnham’s plan for Manila, Haussmann’s plan for Paris, or Col. McMicking’s plan for Makati.

Built over time

While some places are conceived through some moment of epiphany by a visionary planner or ruler, their ideas are often frameworks at best.

The reality is that cities are built over time and often less deliberately—shaped by the shifting forces of market, capital, policies, demographics, nature, technology, and the actions of generations of agents who influence how a place evolves through time.

Cities are hardly the outcome of some victorious moment. More frequently they are born as a response to crisis or even conflict. Cities, like most complex systems, go through a process of evolution and co-evolution—adapting to changing contexts, much like how living organisms adapt based on information in their surroundings.

Incremental ‘mutations’

Indeed, urban planners have adopted this biological metaphor and refer to this process of city evolution as morphogenesis. Gradual changes in the environment trigger incremental “mutations” in cities, similar to other adaptive systems.

While some elements of cities achieve a certain level of permanence (buildings, roads), occasionally a major disruption can totally alter the course of societies, allowing them to leapfrog radically into a new form, a branching of the new from the old.

History shows that more fundamental than mere human ingenuity, the combination of climate and geography has been the impetus for most of these revolutionary steps in the development of cities and societies.

Formation of cities

Did climate change lead to the formation of cities? Some experts believe so.

The long cycles of planetary ice ages and warming allowed prehistoric people to shift from nomadic hunting and gathering to farming in settled villages in ancient Mesopotamia (the region occupied by present-day Iraq and portions of Syria, Turkey, and Iran), a cultivable valley between desert and mountains that flourished as a fertile oasis when the Tigris and Euphrates rivers overflowed from monsoon rains in the mountains. It is here where early settlements began and thrived for millennia.

Around 10,800 B.C.E., regional temperatures abruptly fell some 12 degrees Fahrenheit, part of a mini ice age that lasted 1,200 years. This dramatically reduced the rain-bearing monsoons in the mountains surrounding Mesopotamia, affecting crop yields in the valley, and forcing early settlements to either flee their farming villages or merge into a few large sites in the region.

Small tribes that banded together into larger settlements enabled more cooperation, specialization, and a more hierarchical social organization that facilitated endeavors such as building irrigation systems and rationing resources, record-keeping, writing, inventing new tools, constructing monuments and temples, and creating more sophisticated systems of organization (e.g., laws, bureaucracy, dynasties, religion, forced labor, culture).

From scarcity and crisis

These turned villages into cities, and eventually, into states and empires. While the transformation took millennia, ancient climate crisis allowed human beings to evolve the complex adaptive system we now broadly call civilization, allowing them to control and master natural forces.

From this perspective, cities are not just the outcome of abundance and opportunity, as they are normally perceived, but entities that actually emerged from scarcity and crisis.

From their earliest beginnings up to modern times, cities have been shaped by these same forces. Fortified cities, colonial towns, shanty areas, ethnic districts are all rooted in humanity’s history of seeking opportunity and escaping crises.

Climate change

Today, cities are once again besieged by crises.

The future of human civilization is threatened by climate change, albeit one caused by human civilization itself. Extreme weather, ground subsidence, rising sea levels, resource scarcity, biodiversity depletion, and other forces pose an existential threat to society.

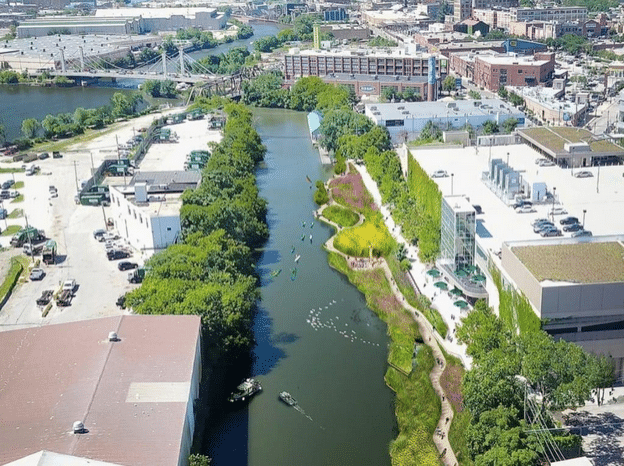

Some visionary leaders respond to these forces by taking drastic steps such as building new cities on safer ground (e.g., Indonesia’s Nusantara). Others try to adapt their cities by mobilizing technology and brute infrastructure to meet these forces head on (e.g., the Thames Barrier in Great Britain); others by small, incremental steps that attempt to reduce the impact of these forces (e.g., urban rewilding).

Resilient cities

If the past were to offer some hope, it is in the fact that ancient existential crises had set the stage for transformative societal change, which in turn propelled human society to its next evolutionary step.

Today, we are relying on some form of technological fix, some form of master plan or blueprint that can avert the crisis we face, short of the radical undoing of society as we know it.

In the past, we found the solution in cities. It is possible that the response to our present crisis still lies in cities themselves. It all depends on whether we can harness our collective ingenuity and focus them toward building better and more resilient urban societies.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a masterplanning and design consultancy practice. Visit www.jlpdstudio.com