Mega events, international encounters, and urban transformation

Cities are internationally mediated spaces that host a variety of cultural encounters.

While globalization is fueled by the movement of transnational entities that facilitate economic integration, there are other agencies of transformative cross-border exchanges.

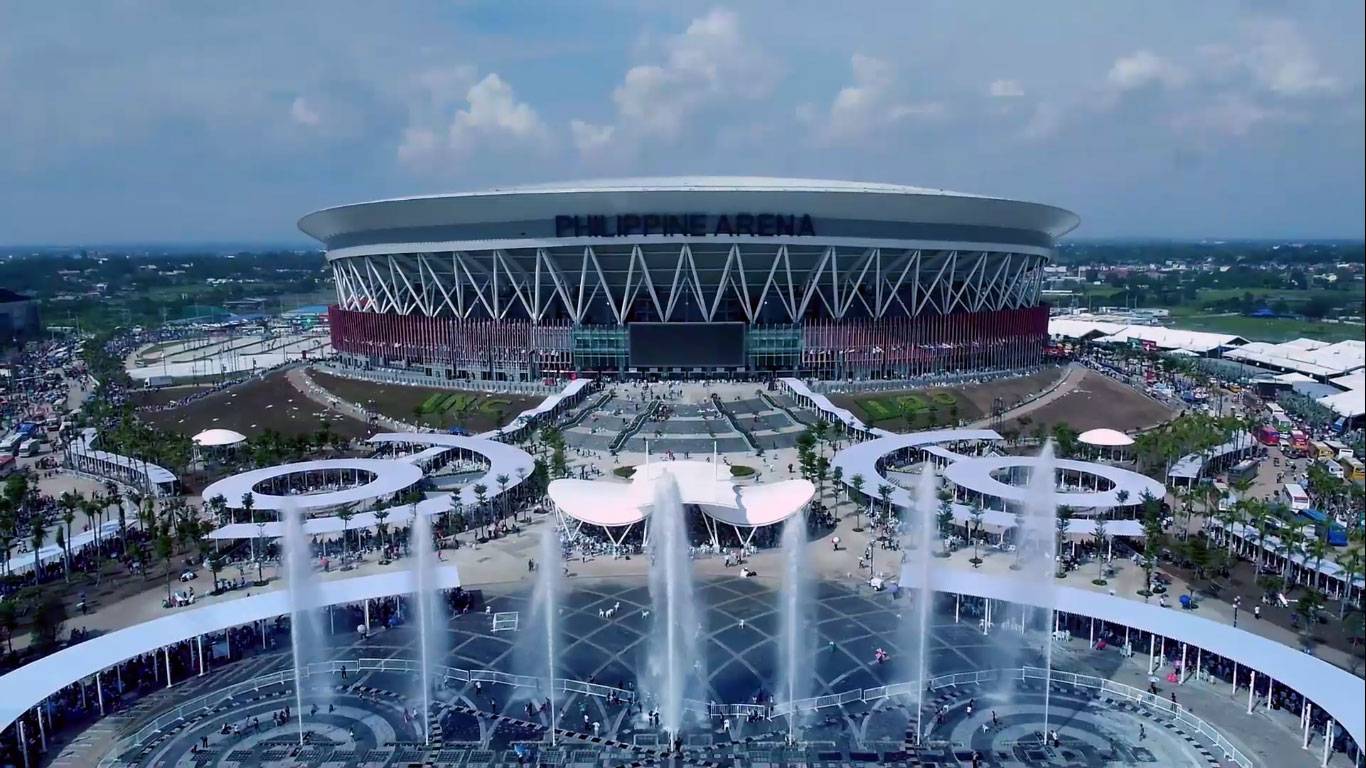

Mega-events such as the Olympics, FIFA, World Cup; international competitions like beauty pageants; and global meetings like the Apec Summit can significantly redefine the urbanscapes of host cities. Such transformations can be so physically dramatic that social and economic ramifications are felt long after the events have ended.

Urban spaces that deliver

The hosting of these big events is often competed over or subjected to qualifiers to ensure that the selected city will deliver.

Being the host city goes beyond ensuring the availability of venues such as sports facilities, theaters, exhibition and meeting spaces. Adherence to programs and schedules requires other enabling infrastructure that will facilitate urban mobility.

The consequent surge in demand for accommodation would vary depending on the nature of the event. The security and safety of both the locals and the visiting entities are of paramount importance as these events get beamed to the whole world through different media platforms.

Public places that can cater to the leisure activities in between and after formal events should be able to complete the visitors’ experience in the city. Places of cultural significance add value to cities that hope to host these events, which also boost tourism (Heslop, Nadeau, O’Reilly, 2010). These international convergences provide opportunities for cities to put on the spotlight their built heritage and cultural treasures.

Place thresholds in terms of volume of people and intensity of activities should be considered in the hosting process (HTTPS://

WWW.MUANGTHONGTHANI.COM)

Spatial consequences

Given the scale and reach of these international events, planning for and holding of the activities involve investments that manifest in the built form of the city.

Transformations may be due to new buildings and infrastructure. These may also be results of renovations and adaptive reuse of existing facilities. Sanitizing places to be visited comes with the hospitality goals, and cleaning up can range from repainting walls to relocating people. Evicting families as in the case of Rio de Jaineiro had to come with the preparations for two world sports events (Aragang, Maenn, 2013).

The programmed activities have direct and induced spatial effects as economic activities are stimulated. Material and service suppliers, restaurants, hotels, among others, are activated beyond the usual business transaction levels.

Transformation period

The consequent surge in demand for accommodation would vary depending on the nature of the event. (HTTPS://ALLIANZ-ARENA.COM)

The effects of international events may be seen beginning from the issuance of information about formal hosting. Press releases trigger sequences of reactions that are expressed in space improvements, property investments, and other space planning decisions that require gestation periods.

The transformative effects continue to be expressed many years after the event. The lifestyle changing effects of new facilities, changes in neighborhood quality, city branding that results from visitors’ impressions, and place-activity associations are felt long after the intended purpose of the built interventions have been served.

Mitigating adverse effects

Place thresholds in terms of volume of people and intensity of activities should be considered in the hosting process. Carrying capacities—defined by infrastructure, transportation, utilities and support facilities—need to be considered so as not to breach safety and well-being limits.

Inclusivity goals translate to housing sites and private properties being respected as public events are being carried out.

Understanding the gentrifying and socially dividing effects of interventions requires foresight and vision-led planning. These events should be able to feature rather than erode local culture. Community participation in planning and implementation can tap human resources while gearing the events towards common goals.

Integrating with existing urbanscapes

Carrying capacities need to be considered so as not to breach safety and well-being limits. (@PARIS2024)

Effectively integrating new architecture and infrastructure with existing urbanscapes and their underlying social structures can better ensure the sustained use of new investments.

Facilities ending up as abandoned spaces are those that lose relevance after the event. Integration translates to forms that are catalytic and at the same time coherent with local sensibilities. It also calls for space functions that can be woven into the city’s existing and envisioned socioeconomic networks.

International events celebrate the coming together of culture, ideas, technology and activities. The people dimension of these convergences should, therefore, guide the conceptualization, planning and holding of these events that are expected to create waves of positive and negative changes.

References: Aragang, T., Maenn, W. (2013). Mega Sporting Events, Real Estate, and Urban Social Economics- The Case of Brazil 2014/2016. Hamburg Contemporary Economic Discussions No. 47; Heslop, L. A., Nadeau, J., & O’Reilly, N. (2010). China and the Olympics: Views of insiders and outsiders. International Marketing Review, 27(4), 404–433

The author is a Professor at the University of the Philippines College of Architecture, an architect and urban planner