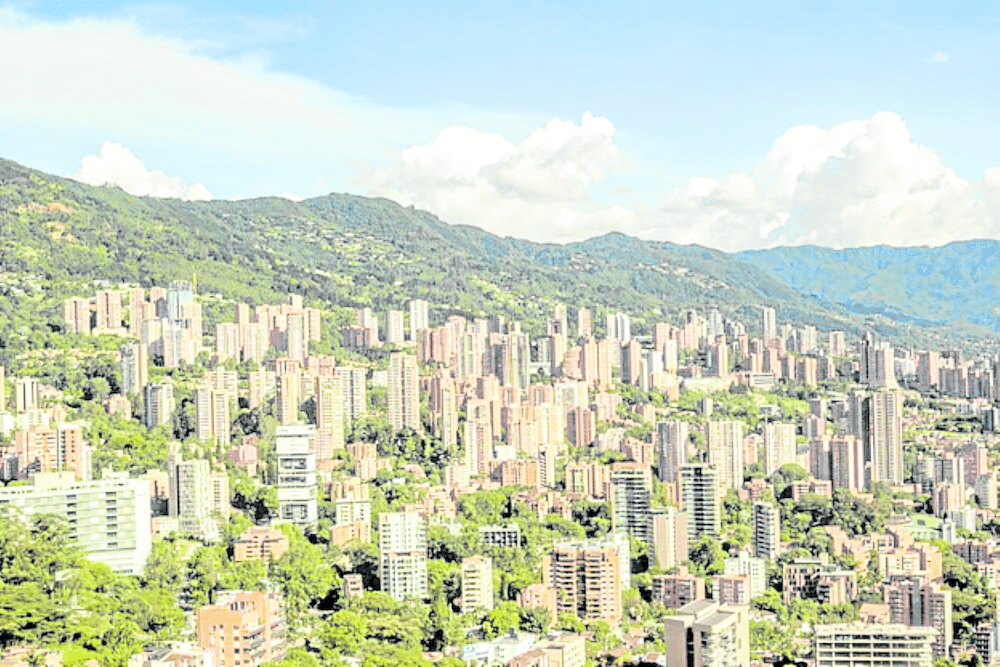

Medellin, Colombia (Cesar Girolimini via Shutterstock)

The aftermath of Supertyphoon Carina made us ponder the new reality our cities are facing.

After several months of record hot temperatures in Metro Manila, we faced record-breaking rainfall that surpassed the intensity of Typhoon Ondoy 15 years ago. The massive rainfall experienced in 2009 prompted civil engineers to revise planning standards for drainage infrastructure. New benchmarks were set. But two weeks ago, the 100-year Ondoy event was surpassed by Carina.

Extreme weather events

These events of extreme heat and extreme rainfall, and thus of extreme calamities, are unlikely to be the last we will witness.

Unprecedented weather events will become more severe and more frequent, affecting agriculture, water supply, energy production, and transportation, straining our socioeconomic systems and all aspects of daily life—cascading effects brought about by a warming planet.

Climate scientists bleakly predict that even if for some miraculous reason we can immediately bring our global carbon emissions to zero, the protracted and compounded effects of historical emissions—and therefore of global warming and climate change—will persist, possibly for decades. We have entered an era where extreme weather events are the new normal.

Whether our cities buckle, bend, or cope under these extreme conditions will depend on the paradigms we use to deal with them. Developing nations, with larger populations and lesser resources than their first world counterparts, are most vulnerable, and therefore must find ways to deal with the climate crisis more efficiently and effectively.

Flooding in Metro Manila due to Supertyphoon Carina (Gaemi) (Ted ALJIBE via AFP)

Creating a new capital

Indonesia’s response to extreme climate is drastic: moving the capital to the island of Borneo.

The current capital, Jakarta, is known as the world’s most rapidly sinking city, and some experts estimate that the city will be fully submerged by 2050. Rising sea levels and overextraction of groundwater have led to sinking by as much as 11 inches per year in some areas. While flooding has long been a problem in Indonesia’s capital, the ground subsidence in recent years has forced the city to respond with heavy engineering through massive seawalls and engineered rivers.

Still, past mega infrastructure projects have been no match to storm surges, and the city continues to sink. Already, 40 percent of the city is now below sea level, with flooding in coastal neighborhoods occurring daily. Building a new city from scratch was Indonesia’s ultimate response, and construction of the new capital, Nusantara, is now underway.

Green Corridors Project

Meanwhile, Medellin, Colombia’s approach to extreme weather is different. The city had high levels of urban heat islands which resulted in high temperatures even in the evenings.

In 2016, Medellin implemented the Green Corridors Project, which involved the creation of a 20-km interconnected network of shade by transforming 18 roads and 12 waterways into a green space. The aim was to plant over 800,000 trees and 2 million plants throughout the city through a network of 30 landscaped corridors that connected over a hundred parks throughout the city.

The result: The project has reduced the urban heat island effect and brought down average temperatures throughout the city by 2 degrees Celsius. The project has also seen cascading benefits—reduced air pollution, lower energy consumption, improved citizen health, and higher urban biodiversity.

But the real innovation that enabled such an impact was its participatory planning process, where the citizens of the city decided on how and what infrastructure would be implemented through their municipal participatory budget.

Artist’s concept for Nusantara, Indonesia (Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing, Republic of Indonesia)

Philippine cities

Medellin and Jakarta differ in their approach to dealing with the changing climate according to their respective context and climate conditions. Jakarta’s approach is top-down and heavy-handed, while Medellin’s is bottom-up and utilizes a softer, nature-based approach.

Both are sweeping and significant and each tells a different story of urban climate adaptation through systemic approach. Both highlight the importance of responding to the changing climate with urgency.

Philippine cities will continue to experience extreme heat and extreme flooding in the coming years. What is our planned response?

Climate change is human-induced—not some uncontrollable “act of God”. This offers some hope that what we choose as our response can also avert it. Business as usual will bring about the worst case scenario of climate impact. The way to cope with climate change is by changing with the climate.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning and design consultancy practice. Visit www.jlpdstudio.com