Parental authority and custody over an illegitimate child

Our Family Code defines legitimate, illegitimate and legitimated children.

A legitimate child is one that is conceived or born during the marriage of the parents, which includes children conceived as a result of artificial insemination, with the sperm of the husband or that of a donor into the wife. (Art. 164, Family Code)

On the other hand, Illegitimate Children are those conceived and born outside a valid marriage. (Art. 165, Family Code)

READ: The rich illegitimate brother

Legitimated children are children conceived and born outside of wedlock of parents who, at the time of conception, were not disqualified by any impediment to marry each other, or were disqualified only because either or both were below eighteen years old, and whose parents subsequently contract a valid marriage. They enjoy the same rights as legitimate children and the legitimation retroacts to the time of birth. (Art. 177 to 180, Family Code)

It is the natural right and duty of the parents to have parental authority and custody over their unemancipated children, which include caring for and rearing them for civic consciousness and efficiency, and the development of their moral, mental, and physical character and well-being.

The father and mother shall jointly exercise parental authority over their child. In case of disagreement, it shall be the father’s decision which shall prevail unless there is a court order to the contrary. (Art. 209, 210 and 211, Family Code)

In cases where one parent dies or is absent, the remaining parent shall continue to exercise parental authority over the child. Remarriage of one parent, where the other is still living, does not affect the parental authority of both parents , unless the court appoints another person to be the guardian of the child. (Art. 212, Family Code)

In the unfortunate event of separation of the parents, parental authority shall be exercised by the parent designated by the Court, which shall take into account all considerations, especially the choice of the child over seven years of age, unless the parent chosen is unfit. A child below the age of seven is deemed to have chosen the mother. (Art. 213 and 129, Family Code)

READ: EXPLAINER: Legitimate children can use their mom’s surname — SC

In case of death, absence, or unsuitability of the parents, substitute parental authority shall be exercised by the surviving grandparent. In case several survive, the one designated by the court, shall exercise parental authority. (Art. 214, Family Code)

It is a fundamental principle that in all questions relating to the care, custody, education, and property of the children, the Courts will consider what is in the best interest of the child.

Notably, the right of custody accorded to parents spring from the exercise of parental authority. The general rule is that the father and mother jointly exercise parental authority and custody over their child. For illegitimate children, it is the mother that is given parental authority over the child. (Art. 176, Family Code)

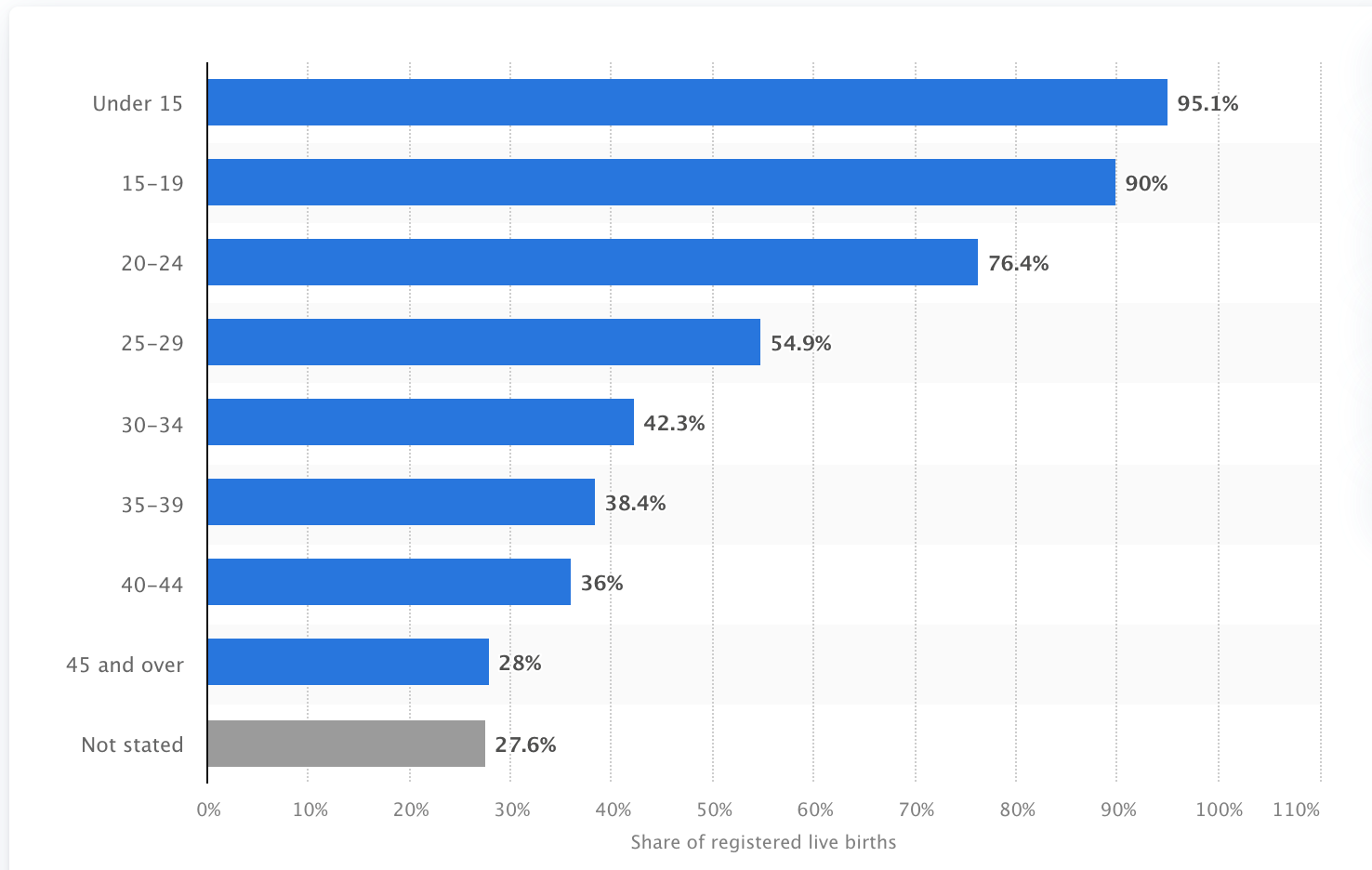

In modern times, there is hardly any more negative stigma attached to single parenthood and illegitimate children. In the Philippines, the share of illegitimate children to live births is quite significant as shown by the table below.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1448623/philippines-share-of-illegitimate-live-births-by-age-of-mother/

(https://www.statista.com/statistics/1448623/philippines-share-of-illegitimate-live-births-by-age-of-mother/)

Our Family Code also provides for the rules on parental authority and custody over illegitimate children. In the case of Sps. Gabun, et al. v. Stolk, Sr. (G.R. No. 234660. June 26, 2023), Mr. Stolk, Sr. lived with Catherine, the mother of Stolk, Jr., in America without being married to each other. Catherine returned to the Philippines to give birth to their son, but died during childbirth. Nora and Marcelino, the collateral grandparents, or siblings of Catherine’s parents, of Stolk, Jr. took care of and had custody of Stolk, Jr.

Mr. Stolk, Sr. claims that the grandparents prohibited him from seeing his child, Stolk, Jr., which prompted him to file a Petition for Habeas Corpus with the Courts for the permanent custody over his minor son Winston Clark Daen Stolk, Jr. (Stolk, Jr.).

After a DNA test confirmed that Stolk, Sr. was the biological father of Stolk, Jr., the trial court awarded custody of Stolk, Jr. to his father, over the objections of the grandparents who claimed that Stolk, Sr. was not fit to assume parental authority. They reasoned that he was a divorcee, a convicted felon, having been deported from America to his native country, Suriname, by reason of a case against him for illegal transport of firearms and, over the written preference of Stolk, Jr., who wanted to remain with his grandparents.

The Supreme Court reversed the trial court’s ruling and returned the case to it ordering the trial court to determine and evaluate who should have custody of the child based on the parameters laid out in the Rule on Custody of Minors. The Supreme Court declared that the trial court did not consider facts, circumstances, and conditions to arrive at a conclusion of what would be in the best interest of of Stolk, Jr.’s survival, protection, and feelings of security, which would best encourage his physical, physiological and emotional development.

READ: How much is my inheritance?

The Court explained that as a rule, the father and the mother shall jointly exercise parental authority over the persons of their common children. However, with respect to illegitimate children, Article 176 of the Family Code explicitly grants the sole parental authority to the mother, notwithstanding the father’s recognition of the child.

In case of the death, absence, or unsuitability of the mother, substitute parental authority shall be exercised by the surviving grandparent pursuant to Article 214 of the Family Code

In case of death, absence or unsuitability of the parents or the mother in the case of an illegitimate child, substitute parental authority shall be exercised in the following order (1) surviving grandparent, (2) oldest brother or sister, over twenty-one years of age, and (3) the child’s actual custodian, over twenty-one years of age. (Art. 216, Family Code)

The Court clarified that the order above should not be understood to disqualify the father of illegitimate children automatically and absolutely as it recognized, in a previous case, the father of an illegitimate child may exercise substitute parental authority and be given custody in situations where he is the “child’s actual custodian.”

Moreover, while the Court declared that in the meantime, the grandparents of Stolk, Jr. are granted substitute parental authority and custody under Articles 214 and 216 of the Family Code, this declaration is not final and absolute.

Section 14 of the Rule on Custody of Minors issued by the Supreme Court (A.M. No. 03-04-04-SC, April 22, 2003) enumerated factors that must be considered in determining the issues of custody under the principle of the best interests of the minor taking into consideration the totality of the circumstances and conditions, some of which are:

a. Extrajudicial agreement of the parties;

b. Desire and ability of one parent to foster an open and loving relationship;

c. The health, safety and welfare of the minor;

d. Any history of child or spousal abuse by the person taking custody;

e. The nature and frequency of contact with the parents;

f. Habitual use of alcohol and dangerous drugs or regulated substances;

g. Marital misconduct;

h. The most suitable physical, emotional, spiritual, psychological and educational environment for the holistic development and growth of the minor; and

i. The preference of the minor over seven years of age and of sufficient discernment, unless the parent chosen is unfit.

The Courts may also order a social worker to make a case study of the minor and to prepare a report and recommendation.

(The author, Atty. John Philip C. Siao, is a practicing lawyer and founding Partner of Tiongco Siao Bello & Associates Law Offices, an Arbitrator of the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission of the Philippines, and teaches law at the De La Salle University Tañada-Diokno School of Law. He may be contacted at jcs@tiongcosiaobellolaw.com. The views expressed in this article belong to the author alone.)