How to unmask the smugglers

This was the conclusion reached among BOC and agriculture leaders during a June 19 meeting. The BOC was represented by Commissioner Bienvenido Rubio and Deputy Commissioners Vener Baquiran and Juvymax Uy. The agriculture leaders were from the Federation of Free Farmers (FFF), Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura, and Alyansa Agrikultura (AA). The meeting was prompted by Finance Secretary Ralph Recto, who wanted a significant increase in tax collections.

Recto publicly stated he did not want new taxes or increased rates. But since additional government revenue was needed, Recto said the BOC had to significantly increase its collection.

Let’s look at the problem first. The corruption BOC is usually accused of happens largely through technical smuggling via imported product undervaluation.

Measuring smuggling

Many years ago, a finance secretary admitted smuggling was difficult to measure. But a leader from AA suggested this could actually be estimated by looking at the amount exporting countries say they send to the Philippines then comparing it with the amount the BOC reports that we receive. The difference is a smuggling indicator.

In other words, if an exporting country says they sent us $100 million, but we report that we received only $70 million, then $30 million was lost to smuggling.

Article continues after this advertisementBased on data provided by the United Nations Comtrade, there has been an astounding increase in smuggling over the years. In 2019, the difference between data reported by exporting nations and the value the Philippines actually received was P500 billion. It more than doubled to P1.2 trillion in 2021.

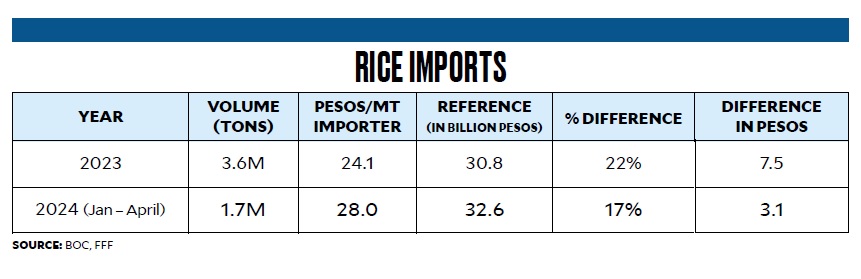

Article continues after this advertisementFFF’s Raul Montemayor provided a summary (check table).

If the reference value (which reflects the average true value from government and private sector sources) is used instead of the reported undervalued amounts from illegitimate importers, we would be able to collect from rice imports alone an additional P9.4-billion revenues for 2023 (at 22-percent undervaluation) and P1.8 billion from January to April for 2024 (at 17-percent undervaluation).

The BOC must finally address the problem of undervaluation especially now that their jobs are at stake.

Importer action

Why is this undervaluation happening? Importers emphasize a World Trade Organization (WTO) rule that the only value the BOC can use is the ‘‘transaction value” importers record in their submissions. Many importers undervalue to pay less taxes. Many BOC corrupt officials turn a blind eye to this, then get paid by the importers for their blindness.

If these illegitimate importers are suspected of lying on their submitted transaction values, WTO allows six other methods of computing the correct import value.

One way is to simply get the actual invoices with the correct value from legitimate importers who are actually paying the correct higher taxes based on their higher recorded transaction values. The BOC said, however, they do not have enough of these to justify collecting the correct taxes.

During the June 19 meeting, the agriculture leaders committed to talk to the legitimate importers and get their invoices with the correct higher transaction values.

Rubio welcomed this move. He can now use these documents to negate the false low “transaction values” and collect much higher taxes based on the correct values. This should be used as a key performance indicator at the BOC.

The challenge now is whether the legitimate importers will be willing to submit their invoices while earning the ire of the illegitimate ones who will now have to pay the higher correct taxes. The outcome of this effort will be known in the next few weeks.

This should determine the success or failure of Recto’s efforts—and the job security of the BOC officials who are responsible for such a critical task. INQ