Keeping heritage conservation apace with modernization

When the Department of Public Works and Highways announced last year the replacement of the aging Ysalina Bridge, heritage advocates raised a howl of protest.

They pleaded for the agency to find a way to beef up its structural integrity without wiping out an important relic that has stood witness to the city’s growth and development.

Rightly so.

According to Jerome de la Fuente, an experienced international hotelier, cultural heritage is an important ingredient in Cagayan de Oro’s brand story.

Named after the late Misamis Oriental Gov. Paciencio Ysalina, the bridge, which spans an area near the City Hall toward the city’s western part, is a testament to the effort to physically unite what used to be isolated settlements of the old Cagayan de Misamis town.

The first bridge that spanned across the Cagayan de Oro River was built around the 1880s, and was made of bamboo hence had to be constantly repaired. It was replaced by a steel structure in 1931 but was destroyed during World War II. The present bridge was constructed in 1946.

Historical details enrich the story of a locality and establish connection with people, which is important for attracting tourists, and eventually business locators, explains De la Fuente, who now runs Limketkai Luxe Hotel.

He points to the need to preserve old houses and structures in the area around Plaza Divisoria, the old business district, and for the local government to devise an incentive program so that the present owners are encouraged to introduce adaptive reuse of their properties.

Challenges

The small property blocks in the Divisoria vicinity, which is also outlying City Hall and the Catholic church, are reminiscent of the physical layout of the old poblacion (town center).

Preserving some neighborhood or some specific structure from being gobbled up by commercial development is a big challenge in the city given the accelerating pace of its economic progress. A prominent example is the decision of Jesuit-run Xavier University—Ateneo de Cagayan (XU) to open part of its 8-hectare campus, which is within the Divisoria vicinity, for mixed-use development.

SEAT OF GOVERNANCE The present site of City Hall has been the seat of governance in the past 140 years.

For heritage advocates, this will desecrate a hallowed historical ground as the campus served as Japanese garrison during World War II, and where many resistance fighters were martyred. Amid this controversy, the university and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines have agreed to establish a historical preservation zone within the campus that will comprise eight buildings of “exceptional and historical significance.”

Established in 1933, XU is the first Ateneo school to achieve university status, in 1958, while also being the first university in Mindanao, attesting to the city’s historic role in developing future leaders in this part of the country.

Heroes all

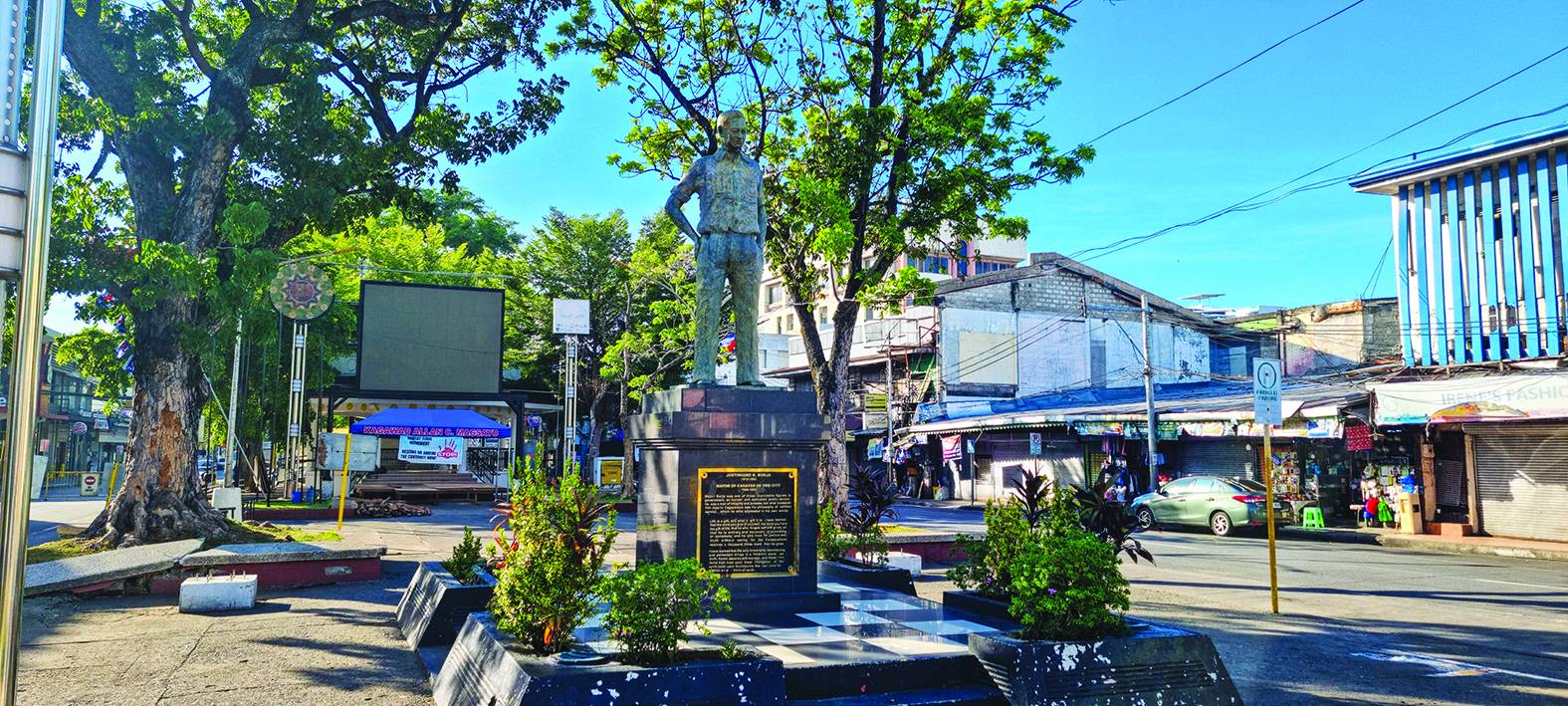

Composed of five different tree-covered parks, Plaza Divisoria, itself, is a storied place. There, one is reminded of the exploits of local and national heroes through the statues erected in every park, and the city’s glorious past as a bastion of colonial resistance whose people value freedom and liberty, and whose leaders are primarily committed to the welfare of the common folk.

One park has an obelisk that features a statue of former President Ramon Magsaysay, celebrating the legacy of the “Man of the Masses.” The El Pueblo A Sus Heroes, or Town Heroes, presents a statue of Katipunan founder Andres Bonifacio raising a bolo in his right hand and a flag in his left. The statue’s base is where the bones of the martyred members of the First Company of the Mindanao Battalion were interred. This unit of the local resistance forces against the American colonizers was led by Capt. Vicente Roa and fought during the battle of Agusan Hill on May 14, 1900.

ICON AND LANDMARK The city’s iconic “motorela” passes by the historic Balay nga Bato of the Sia Ygua family

The Kiosko Kagawasan, or Freedom Kiosk, hosts the statue of former City Mayor Justiniano Borja done by National Artist Napoleon Abueva. Borja was the city’s chief executive from 1954 to 1964, and was touted as the local equivalent of then Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson who was regarded for his unwavering political will as a leader, and tireless pursuit of the common good.

Of course, there is a statue of Dr. Jose Rizal, already 120 years old, which means it was built less than a decade after the national hero’s martyrdom in Luneta.

Journey through history

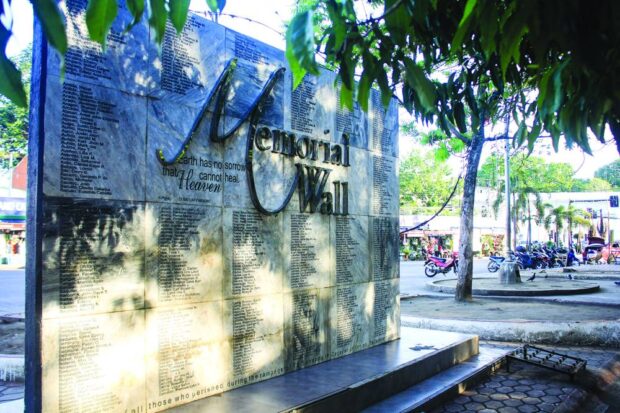

PAINFUL MEMORY The Sendong Memorial Wall at Gaston Park is a reminder of the 2011 catastrophe when the city was battered by floods, killing hundreds of residents. —PHOTOS BY BOBBY E. LAGSA

Two blocks away is City Hall, built in 1940 on the same grounds where the old Casa Real, the Spanish-era seat of governance, once stood.

Across City Hall is the St. Augustine Metropolitan Cathedral which is both a place of worship and a cultural monument. The original structure was built in 1624 by Fray Agustin San Pedro, which means it has stood as a bastion of the Catholic faith in the last 400 years.

The church was destroyed several times and had to be rebuilt. Constructed in 1946, the present structure combines modern and traditional architectural styles. But the wooden cross which stands in front of the cathedral was erected in 1888.

RIZAL’S CAUSE The 120-year-old monument of Dr. Jose Rizal at Plaza Divisoria speaks of the local community’s deep feelings for freedom and liberty.

Across the cathedral is Gaston Park, the main plaza of Cagayan de Misamis town during the Spanish colonial period. With a view of the church and the seat of government, one can be transported to those times centuries back when there was not much distinction between civil and clerical administration.

Beside the church convent is the old water tower which was converted into the city museum. Constructed in 1922, the cylindrical structure used to be the tallest structure in the city that survived the heavy bombings during World War II. Today, this could be the oldest surviving public infrastructure in the city.