Time a loan will tell: Where does bank credit go?

Do you ever wonder where bank loans go?

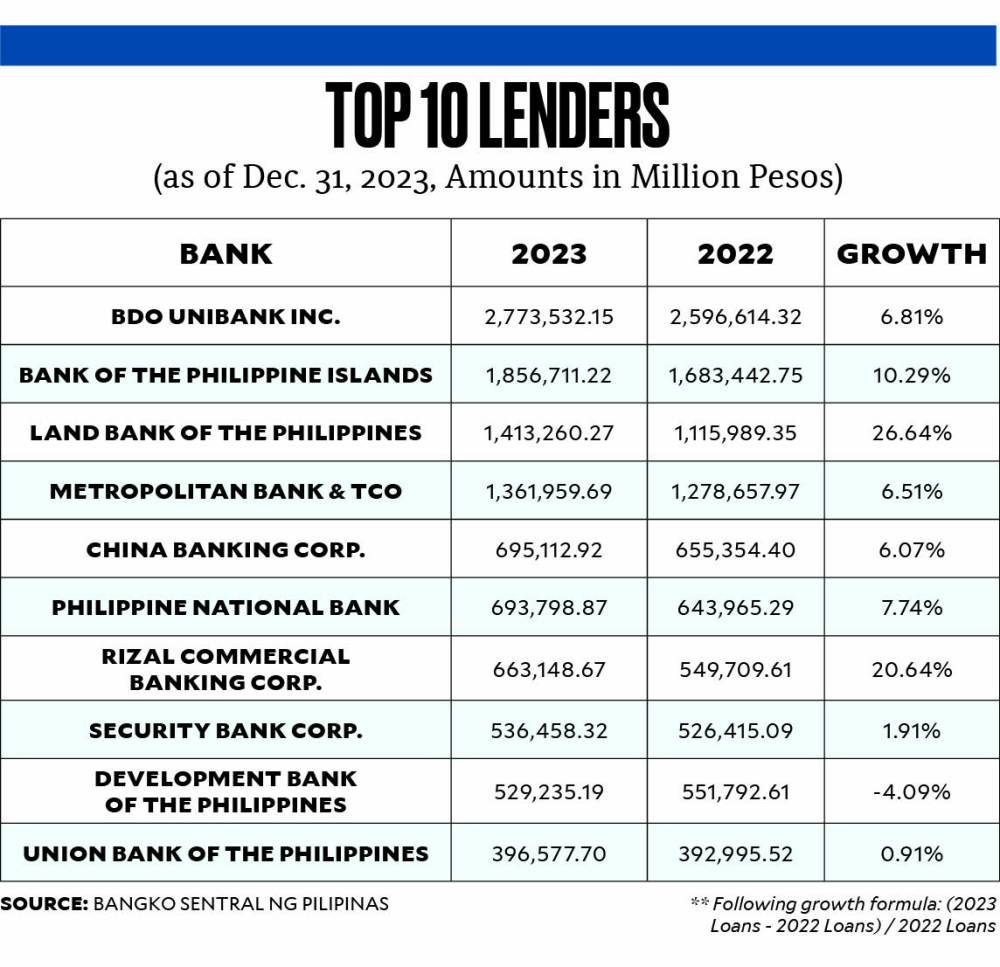

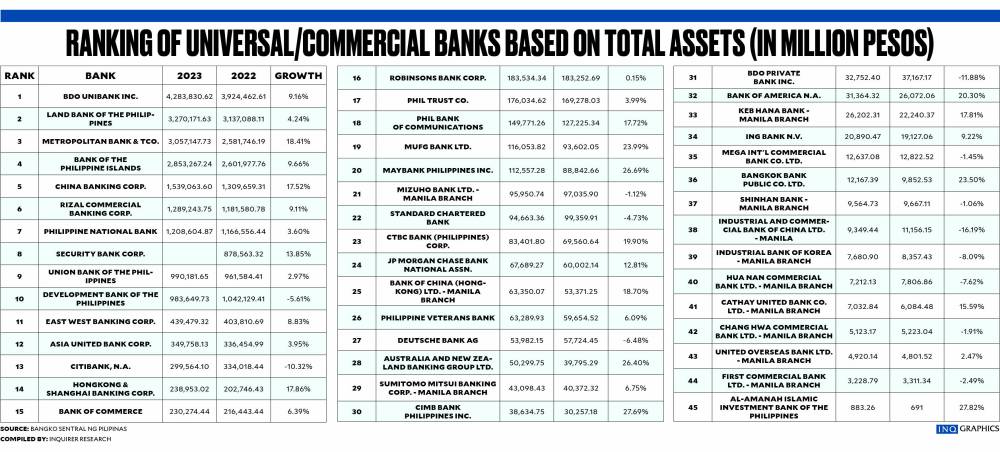

With financial conditions remaining tight, securing bank loans can be more expensive now than ever before for many Filipinos. Data from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) show that credit growth in the country has slowed since the start of the central bank’s aggressive tightening against inflation, although outstanding loans of the country’s big banks—excluding their lending with each other—managed to grow at a faster rate of 8.6 percent in February to P11.61 trillion.

If we consider the entire Philippine banking system, total outstanding bank loans amounted to a larger P12.57 trillion as of February.

“The reason for the underperformance of bank lending can be tied to elevated borrowing costs, showing clearly the negative impact of policy rate hikes on growth momentum,” Nicholas Mapa, senior economist at ING Bank in Manila, says in a commentary.

But, again, where does all that money go?

By major segments, latest figures from the BSP show 80.46 percent of these loans are extended to local businesses while 13.62 percent are secured by Filipino households. Also, 3.34 percent of these borrowings are in the form of reverse repurchase agreements, or securities the BSP intends to buy back at a later date, while the remaining 2.58 percent is granted to foreign borrowers.

Broken down, domestic enterprises engaged in real estate activities corner 19.31 percent of total loans in the local banking system, taking the largest share. Coming in at second place are companies in the business of “wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles, motorcycles” with a 10.91-percent share.

Firms engaged in production of electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply take the third biggest slice (9.9 percent) of the credit pie, followed by manufacturers with a 9.74-percent share.

On the household level, credit cards account for 5.68 percent of the local banking industry’s total outstanding loans, while motor vehicle loans corner a smaller 4.07-percent share. Salary-based loans eat up 3.48 percent of the total credit.

Too much household debt?

For ING Bank’s Mapa, it remains unclear if the uptick in bank loans—despite stubbornly high inflation that’s beating household savings—is not a symptom of a creeping economic problem.

Mapa notes that loans to consumers have been surging over the past 24 months driven by “the stark increase in both credit card debt and salary-based loans.”

The rapid increase in lending to these sectors, he says, has resulted in consumer credit almost doubling from their pre-COVID levels, with the latest reading at P1.2 trillion from the roughly P587 billion prior to the health crisis.

“This may be viewed as a positive for some but the sustained increase in household debt at a time where savings rates are still well-below prepandemic levels could eventually be a worrisome trend,” Mapa says in a commentary.

Moving forward, the ING bank economist expects elevated borrowing costs to weigh on the economy, which may have a hard time hitting a 6-percent growth.

“Rate hikes have a negative impact on growth, and although we may still see growth remain positive, we can only contemplate how much higher our GDP (gross domestic product) growth would be had policy rates not been so restrictive,” Mapa says. INQ