JLPD’s planning and design process

At a recent talk to young project development officers of a leading real estate company, I found it necessary to introduce some fundamentals that are critical in the property development process.

Real estate development is a complicated and convoluted process involving multiple, sequential, and parallel work streams that often vary per organization.

Design

An often misunderstood and underestimated component of project development is the design of the product itself.

Some architects consider design as an end in itself (I am using the term architect here in the broad sense, encompassing other allied design fields such as engineering, landscape design, interior design, among others). But within the broader context of project development, design is simply a means towards a financial end.

In a highly competitive and capital-intensive business such as property development, shortening the “means” to reach the “end” will always be advantageous and is often an expressed goal. From a developer’s perspective, design is a “cost” of doing business—something that needs to be expedient, yielding the highest value for the least amount of investment in time and money.

But expedience can only happen if all variables are known, and each step is targeted and deliberate. The nature of property development, however, is one where each site and project is unique, and therefore expedience is limited by many unknowns that could impact the performance of a given project. This is where the distinction between planning and designing gains more focus.

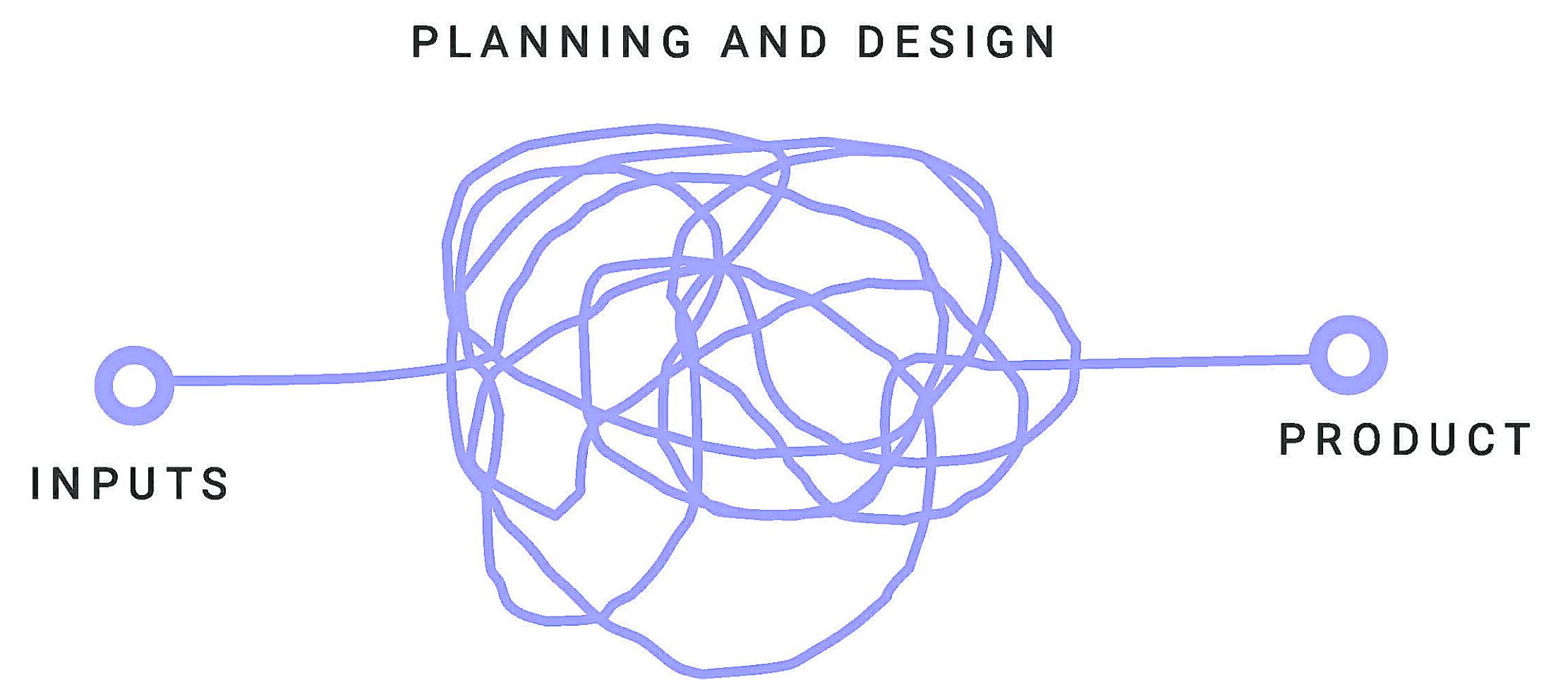

The process of design, just like the process of development, can be messy. (IMAGE BY THE AUTHOR)

Planning

What is planning? And how is it different from design?

Within the realm of property development (and the architectural field), these are almost interchangeable, with their subtle difference from each other known only by practitioners. But in the project development process, the difference could be meaningful, and knowledge of the distinction could avoid protracted and meandering design discussions that end up being wasteful, time-consuming, and costly for property developers.

One may view planning and design as two discrete sub-phases in project development.

A simplified definition that distinguishes these could be that planning refers to seeking out specific outcomes and the avoidance of others, while design refers to the means to order the creation of objects and solutions to achieve a specific purpose.

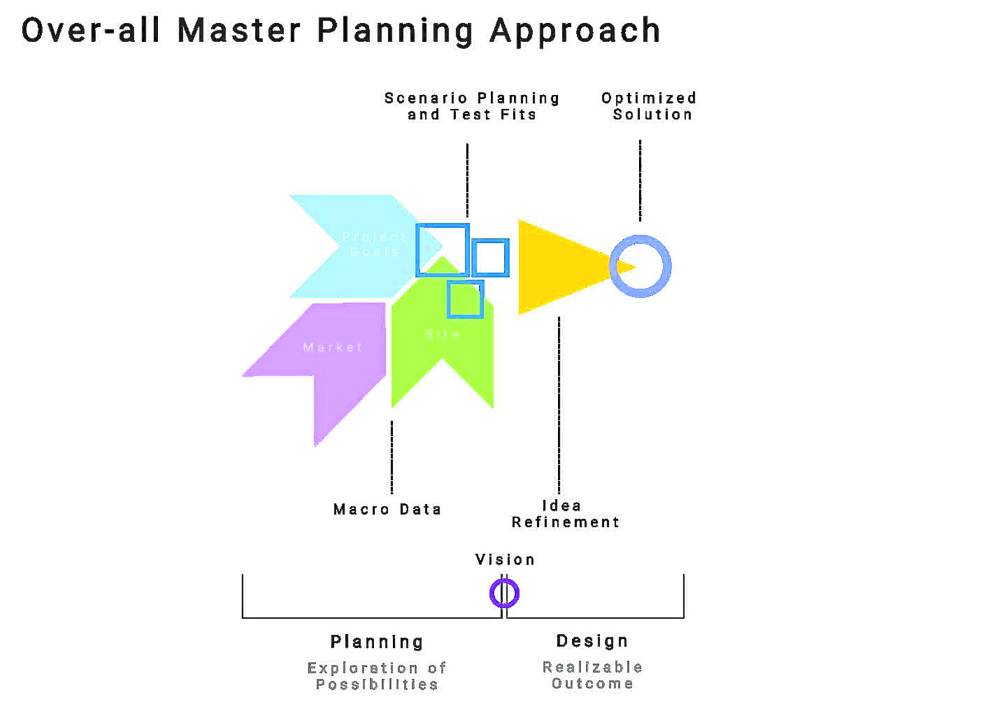

Planning thus aims to sift through several possible outcomes and identify which of these can best satisfy stated goals of the project while discarding those that don’t. This is the stage where volumes of macro and micro data relevant to the proposed project are gathered, sieved, and sorted to provide a comprehensive picture of the various opportunities and constraints.

These analyses inform various scenarios—different possible outcomes that can be considered for the property. These outcomes can vary in terms of land utilization, density, form, access, yield, timeframe—a series of “what ifs” or strawmen represented in diagrammatic form to test or challenge the initial development program by showing other possibilities.

Planning and design require the sieving of information and ideas to arrive at the optimal solu- tion. (IMAGE BY JLPD)

‘Highest and best use’

A typical development brief requires the determination of the “highest and best use”.

The attainment of this ambiguous goal can only be determined if weighed against other possibilities. Only after the rigorous study and elimination of other alternatives can a particular approach be considered optimal, the development program confidently confirmed and clearly delineated, and the project’s purpose articulated.

This, essentially, is the role of planning. What this stage avoids are wasteful misstarts, where designs proceed toward more advanced stages only to be redone because certain programmatic items were not considered early on.

The design stage

So, when does design start? Technically, it begins when the key project parameters, both qualitative and quantitative, have been articulated. The design stage takes off from where the planning stage left off.

Designs are prepared with the intention to implement and realize the plan. It is in this stage where the different design trades—from the concealed engineering systems that allow a building to function, to the more minute and detailed items or interiors, finishes, color, and texture by which the space is experienced through our senses—are organized into a single set of executable documents with the aim of realizing the project.

The design stage also goes through a process of exploration, iteration, modification, refinement, and finalization. The process of design involves putting abstract thoughts into two-dimensional representations that can be implemented in three-dimensional reality. It involves the conversion of the coalesced thoughts of client and the team of experts into visual language and measurable instructions to allow for its transformation into a physical product.

This is where the adage “measure twice, cut once” is most apt. Since rectifications during construction stage are costly, modifications done earlier during the design stage will be more economical.

The most optimal solution

All in all, planning and design involve numerous trade-off discussions in the search for the most optimal solution. It is in this upfront stage of the development process where purposeful thinking about matters that will materially impact project costs, quality, schedules, and marketability happens.

Thus, this is where senior executive time is best utilized to enable early alignment of goals and design objectives, as well as secure faster approvals and directions that will drive the project forward.

Actual design process is less linear than the simplified description mentioned here. The process of managing design will necessarily have to follow a more deliberate path. It involves the organization of complex information flows from multiple sources and actors to serially produce solutions of increasing fidelity toward the resolution of a given objective. In the interest of expediency, the idea of automating design may be tempting (even for designers). However, it removes the process of purposeful thinking in bringing a product to its realization. While a successful project can be the testament of a great design, it could also be the result of a finely tuned design management process.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning and development consultancy practice. Visit www.jlpdstudio.com