Foreign currency bank accounts offer more protection

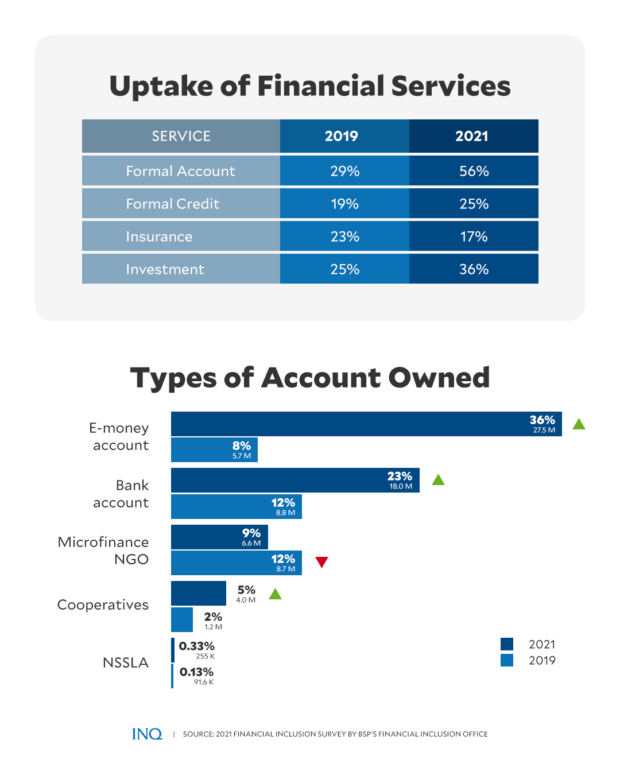

According to The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), “70 percent of Filipino adults will have bank accounts by the end of 2023.” This would be substantially higher than the 56 percent in 2021, and 23 percent in 2017. (https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1206739)

Accordingly, from 2017 to 2023, account ownership will have tripled.

(Source : 2021 Financial Inclusion Survey by the Financial Inclusion Office of the BSP. Note Some adults may have an account across different providers, thus the figures per provider type will not sum up to the overall account penetration)

Based on the 2021 survey of the BSP, socio-economic class, educational level, and age, drove account ownership disparities. In 2021, account ownership in socio-economic class ABC was eighty percent, almost double that of class E, which was at forty four percent. E-money was the most common type of account in socio-economic classes C2, D and E. For classes ABC1, the most common a bank account.

Eighty percent of college graduates had bank accounts, compared to 34 percent for those who only finished elementary. Sixty-five percent of older adults in the age range of 30 to 39 had accounts, compared to younger adults aged 15 to 19 years old, where only 27 percent had accounts.

Seventy-eight percent of account holders used their accounts for payment-related transactions. In 2021, the top payment uses were receiving money at 56 percent, cashless payments/purchases at forty percent, and sending money at 38 percent.

Based on the data gathered by the BSP, those at the lower economic class would most likely have e-money or e-wallets, instead of traditional bank accounts.

Notably, payment-related account usage was particularly high among e-money and bank accountholders.

These statistics are significant as ownership of a formal account is indicative of the level of financial inclusion of Filipinos.

READ: RA 6426 meant to protect foreign depositors

It could be expected that as our population grows older, the rate of account ownership will increase. Moreover, as our population ages, more younger adults will open bank accounts and, as the economy improves, those in the lower economic class will move up the ladder and maintain not only e-money accounts but also bank accounts.

E-money and bank account

In that regard, the basic difference between an E-money and a bank account is that E-money accounts may only be redeemed at face value.

It shall not earn interest nor rewards and other similar incentives convertible to cash, nor be purchased at a discount. E-money is also not considered a deposit, hence, it is not insured with the Philippine Deposit Insurance Corp. (PDIC), unlike bank deposit accounts (morb.bsp.gov.ph, sec. 702 Issuance and Operations of Electronic Money)

With respect to Philippine peso bank deposits and foreign currency deposits, usually in US dollars, there are significant differences aside from of course the difference in country currency of the money held in the account.

Two of the more significant advantages of a foreign currency deposit bank account, for example a US dollar account, over that of a Philippine peso bank account in the Philippines are:

a. Secrecy of bank account is stricter than a Philippine peso bank account; and

b. Protection from attachment, garnishment, or order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or body whatsoever.

It is common knowledge that bank accounts are privileged and generally, they are confidential. Over the years, exceptions have been added, and there are calls from some sectors as to whether secrecy of bank accounts is still relevant or proper today.

Bank Secrecy Law

Despite this, the Philippines still maintains secrecy of bank deposits, whereby any inquiry or disclosure of the bank account information of any person or entity is prohibited save for exceptions provided by law.

Republic Act No. 1405, as amended, provides the Bank Secrecy Law in the Philippines. It was implemented at a time in our history where money in circulation was at a low level and to encourage people to deposit their money in banking institutions, discourage private hoarding of cash and money, and allay fears that bank deposits and their depositors would be scrutinized by the government, the Bank Secrecy Law was passed.

It was a successful measure in that it allowed money to be properly utilized by banks through loans which assisted in the economic development of the Philippines.

READ: In the know: The bank secrecy law

Accordingly, all deposits of whatever nature with banks or banking institutions in the Philippines including investments in bonds issued by the Government of the Philippines, its political subdivisions and its instrumentalities, are hereby considered as of an absolutely confidential nature and may not be examined, inquired or looked into by any person, government official, bureau or office. (RA 1405, Sec. 2)

The General Banking Law of 2000 also provides confidentiality and secrecy of information relative to funds or properties in the custody of the bank. (Sec. 55.1)

Limited exception to secrecy

For Philippine peso denominated bank accounts, the exceptions to bank secrecy are:

1. Written permission of the depositor

2. Cases of impeachment of a public officers

3. Upon order of competent court in cases of bribery or dereliction of duty of public officials, and

4. Cases where money deposited is the subject matter of litigation.

For foreign currency deposit accounts there is Republic Act No. 6426 which provides that all foreign currency deposits in banks are absolutely confidential and shall not be disclosed. The only exception provided by the law is the written permission of the depositor. (Sec. 8)

As can be seen above, Philippine peso deposit accounts have more exceptions than foreign currency bank deposits.

Over the years, there have been additional exceptions to the secrecy of bank accounts which apply to both Philippine peso and foreign currency denominated bank accounts, some of which are:

a. Borrowings of bank directors, officers, stockholders, and related interests;

b. In cases of application for compromise of tax liability, determination by the Commissioner of BIR of a decedent’s gross estate, and exchange of tax information;

c. Anti-money laundering regulatory and compliance as well as activity;

d. The BSP may conduct of annual testing to determine the existence and true identity of the owners of foreign currency non-checking numbered accounts;

e. Inquiry by PDIC and BSP in cases of unsafe or unsound banking and failure of prompt corrective actions;

f. Audit of government deposits by Commission on Audit; and

g. Investigation by PCGG to recover ill-gotten wealth.

On the other hand, there are other additional exceptions which apply only to peso bank accounts.

Aside from the foregoing, in a case decided by the Supreme Court,, it allowed the garnishment of a foreign currency deposit account of a non-resident alien found guilty of raping a minor. This was allowed on the basis of equity (Salvacion v. Central Bank of the Philippines, G.R. No. 94723, Aug. 21, 1997)

Other additional protection

The court declared that the foreign currency deposit of the foreign national deposited in a local bank was only for safekeeping during his temporary stay in the Philippines and that the incentive and protection by the law to foreign currency deposits are designed for lenders and investors.

RA 6426 further provides that foreign currency deposits shall be exempt from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever. This is not applicable to peso accounts.

The additional protection above is quite significant as it exempts the deposits not only from inquiry and other court orders but also from garnishment and attachment to satisfy a judgment by a court.

(The author, Atty. John Philip C. Siao, is a practicing lawyer and founding Partner of Tiongco Siao Bello & Associates Law Offices, an Arbitrator of the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission of the Philippines, and teaches law at the De La Salle University Tañada-Diokno School of Law. He may be contacted at jcs@tiongcosiaobellolaw.com. The views expressed in this article belong to the author alone.)