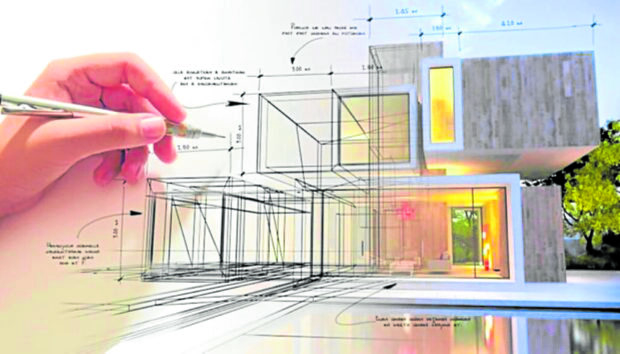

Design, construction, and siting decisions should be made with due cognizance of their public

consequences. (HTTPS://THEARCHITECTSDIARY.COM)

The multi-layered nature of spaces is captured by real estate values that are sensitive to material, people, and place variables.

What individuals, households, and firms consider when making purchase and investment decisions reflects the different facets of properties that evolve as their contexts change over time. The spatial layers are represented by the Hedonic Model variables that include Structure, Location, and Neighborhood Quality (McCann, 2006).

Given that each of these variables is embedded in context, necessitates an understanding of the concept of Externalities. All kinds of interventions in the natural environment, including buildings, land development, and landscape elements, result in varying levels of benefits and disbenefits. Felt benefits constitute positive externalities and disbenefits account for negative externalities (O’ Sullivan, 2019).

Design, construction, and siting decisions, therefore, should be made with due cognizance of their public consequences. These effects explain why some places are favored while others are abandoned or not patronized.

STRUCTURE AND LOCATION

Houses, buildings, and designed open spaces are defined by their physical components. People base their preferences on floor areas, materials, and design specifications. Others give weight to features such as the number of toilets, size of windows, and building amenities.

The integration of technology such as in smart buildings also figures in the processing of purchase decisions. Other features such as space layout flexibility, opportunities for personalization, and indicators of longevity would matter to most users of spaces.

Location features that attract buyers and renters are those that are in proximate distance to where workplaces and community services are situated. The Central Business District serves as the reference point in Von Thunen Model. For firms, distances to sources of production inputs and relative locations of markets or distribution centers would typically matter.

NEIGHBORHOOD QUALITY

Some real estate buyers are willing to trade off structure and location features for the desired neighborhoods. The quality of a property’s neighborhood setting has a lot to do with the positive and negative externality factors.

Peace, security, health and well-being come as priority factors for many and these are provided by settings where incompatible uses are not juxtaposed with each other. For example, many people would mind living near cemeteries, factories, airports, and railways. Others would have different views on being near hospitals, highways, and transport stations. There are also social constructs that make places unfavorable due to their associations. Events that happened there, people who lived in the area, and even urban legends are among the place associations to which pride of place or biases may be attributed.

Land use planning should be able to address incompatibility issues that underlie negative externalities. The provision of open spaces, preservation of view corridors, and infrastructure that supports mobility are among the planning areas that provide opportunities for maximizing positive externalities.

BUILDING-ENVIRONMENT DIALECTICS

Individual and household behavior can also influence real estate values as the effects of their activities go beyond their personal spaces or lot boundaries. By simply keeping their properties clean and well-maintained, the entire neighborhood can enjoy the benefits of the visual amenity that positive behavior produces.

Location features that attract buyers and renters are those that are in proximate distance to where workplaces and community services are situated. (HTTPS://THEPHILIPPINES.COM)

The state of each building affects the neighborhood quality, which in turn induces people to behave in a certain way in their own spaces. The changing collective and cumulative effects of individual building and developing initiatives over the years also chart the path of places toward growth or decline.

PEOPLE AND PLACE DYNAMICS

Buildings do not exist in vacuums and their performance is governed by their contexts. Dynamics between and among social organizations account for collective behavior that manifests in place attributes. The latter is also defined by geographical features that shape collective behavior. These dialectics eventually result in unique place qualities that form the basis for place branding. Place factors support products and services that districts and cities become known for. The specialization process brought about by related activities in turn results in more physical attributes that enhance the distinct image of places.

GOVERNING THE DIALOGUES

With people and places in constant dialogue and mutually affecting each other in constructive or destructive ways, a clear sense of stewardship needs to emanate from community members. Each constituent must inculcate within them the consciousness of how their seemingly minute actions can bear broad-scale consequences. Sensing the intangibles and the layers beneath the visible must precede decisions on what to build and where to develop.

Private developers must be guided by corporate missions that go beyond quick and short-term successes. Businesses associated with products that uplift life quality over the long term reap benefits out of sustained patronage. Projecting beyond bottom-line financial figures promotes trust that builds up with every project that responds to user needs and expectations.

People at the helm of planning institutions should be able to wear many hats to process the many facets of real estate. The ability to weave together concerns coming from various disciplines and sectors will enable pro-activity, flexibility, and agility. Achieving the fine balance between maintaining democratic spaces and governing for the collective good makes for livable neighborhoods that enhance real estate values while promoting well-being.

References:

O’ Sullivan, Arthur. (2019). Urban Economics Ninth Edition. McGraw Hill.

McCann, Philip (2006). Urban and Regional Economics. Oxford University Press.

The author is a Professor at the University of the Philippines College of Architecture. She is an architect and urban planner.