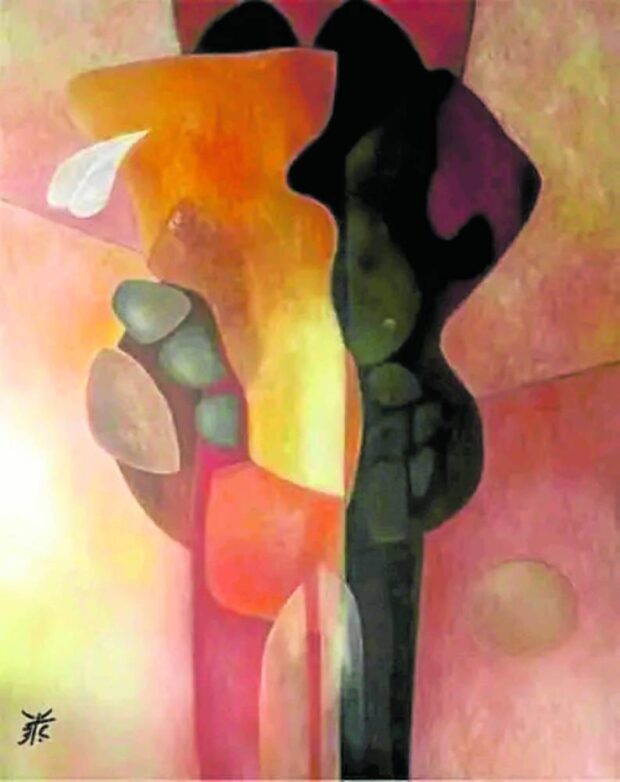

Ega Carreon’s “Union” is already part of Sid Porras’ collection. —Contributed photo

DAVAO CITY—Von Verga, a retired policeman-turned-sculptor, compared a metal sheet to a woman.

“You could not force it to bend to your will,” he said.

Unlike wood that you can carve or plastic which one can bend, or rubber which you can stretch, metal is hard, so you have to find a way how you can form it into the shape that you desire. “That’s why, you have to heat it to soften it, then you have to wait for quite a long time to get results,” Verga said.

At the La Herencia Gallery here, where he joined a group exhibit for the first time, he recounted how many times his hands got burned working with the hot metal because he often got so engrossed at what he was doing, he often forgot that it was hot. He said he had been captivated by hammered bronze, a medium only very few Filipino artists had been using.

Verga, who started sculpting since he was a child, took up criminology and became a policeman in 2002, when he was first assigned here before he was moved to Davao de Oro. He had always sculpted in his spare time and since it usually took a long time to finish, it had taught him patience. When he was still active as a policeman, he would sometimes finish a hand or a finger before he’d leave for duty, then he’d work on it again when he came home from work.

But he finally retired in August this year and joined the artist group Tabula Rasa which opened its show “Timeless,” at La Herencia Gallery this month. His two sculptures, a female torso and a male face were among artworks on display, marking his entry to the ever growing artist community in the city.

Von Verga gazes at his work, a woman’s torso made of hammered bronze. — GERMELINA LACORTE

Creative people

Vic Secuya, the president of the Dabawenyo Artists Federation Inc. (Dafi), made up of 14 artists groups, said it might still be a long way to go before the city could attain a strong creative economy that could, perhaps, sustain artists. But the city is not short of creative people.

“Creatives will always create, no matter what the situation is,” said Secuya, who has mounted 25 solo exhibits and several group shows in various galleries in the last 30 years, including a 2018 painting exhibit in Brussels, Belgium, where he also installed a metal sculpture in a park there.

“But granting that they create simply out of their passion, they had to stop sometimes to earn a living, perhaps, raise a child, so their output is not put at a maximum,” said Secuya, who has been well-traveled, his exposure to various cultures in at least 17 countries he visited gave him an international perspective in art.

Although creative people dreamed and envisioned a creative economy, there was hardly a creative industry in the city because an “industry” denotes a steady production and consumption of goods in a market, he said.

He considered himself among the lucky few who could devote fully to his art because he had what he called a “passive income” to sustain him, he said. Others had to have day jobs to support their families.

Von Verga’s male face, which he started sculpting while he was still a policeman, took him two years to finish because he had to report for police duties in between. —GERMELINA LACORTE

Full-time artists

“There’s no such thing as a full-time artist,” said Ega Carreon, whose group will be doing an exhibit at the Philippine Center in Manhattan next year. “If you spend your whole time in your art only, you will find it very difficult to sustain.”

Carreon made his break in 2000 when his mural-sized work “Bahagi ng Kabuuan,” won the Asian Freeman Fellowship Competition organized by the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson, Vermont.

The two-month fellowship entitled him to a 10-year US visa but he recalled going home to Davao after a three-month stay in the US. But pressed with financial needs as his daughter was about to enter college, he went back to a two-man show exhibit at the Philippine Center in Manhattan.

All his paintings were sold out but even before the end of the weeklong exhibit, he applied for a restoration artist job at Flores & Iva Antiques in New York City and started restoring wood carvings from Africa and wooden statues of saints from the Philippines which he said were patronized by New York’s rich.

Brando Cedeño’s stonecast, “Opulence.” —Contributed photo

Patience

During winter, the wooden statues would crack, lose their hands or fingers. Carreon said he had mastered how to restore them so that they would appear like they were not joined at all and how to paint the eyes so that they would look real; and even how to make these antiques smell like one. The whole thing taught him patience, he said.

While working as the shop’s restoration artist, he studied at the Art Students’ League for two years, at the end of which his work won the competition.

Instead of applying for another grant from the Art Students’ League, he decided to come home to Davao, where he said he was happier. He said he missed the sari-sari store and the public beaches. Back in Davao, he organized workshops, painted portraits to sustain his art.

In 2009, after Carreon returned home, his work, “Katawan at Kaluluwa,” won as a finalist in the Philippine Art Awards. He won another one-month residency in Spain in 2014, where he got to meet with other artists from Australia, France, Norway and America; and the following year, another short residency in Amsterdam. He said his works had veered toward the “spiritual,” a far cry from the “political” when he was just starting.

Brando Cedeño’s nudes were included in the Timeless exhibit at La Herencia while his sculptures were among the few Davao works carried by Gallery Raphael at the Azuela Cove here. The gallery has its branch at Bonifacio Global City and Greenbelt in Metro Manila, where he was able to sell some of his Amorsolo-inspired works.

Since living solely on his art could not sustain the needs of his family, he accepted commissioned works, ranging from big monuments and sculptures to smaller pieces like trophies, tokens and outdoor signages. “But these are not my expressions as an artist,” said Cedeño, who obtained a degree in fine arts, with major in painting at the Ford Academy of the Arts.

Earlier this year, he finished the commissioned sculptures for the Pope John Paul II monument in a seminary in Digos City, Davao del Sur. During the pandemic, he finished the sculptures and monuments inside the Walk of Mercy private sanctuary of businessman George Bian, which included a station of the cross, a chapel and a mausoleum.

Gov’t support needed

According to Secuya, Davao has lots of artists but many of them could not pursue art full time because they needed to take on other jobs to earn a living. That’s why, he said, the government has to come in to support them, whether financial or through a marketing infrastructure that will promote their art. “I would say that even a minimal support of the government is good enough to be able to push the creative people to create,” he said.

Early this year, Davao City Councilor Pilar Braga crafted an ordinance creating the culture and arts office under the Office of the City Mayor.

The ordinance, which is still on second reading, hopes to support Davao artists and includes among its provisions an endowment fund to finance art projects and programs.