Finding the purpose of a place

Bryant Park in New York City is a public space renewalproject, redeveloped in the 1980s using place-making principles.

With the scarcity of vacant commercial land in central Metro Manila, private sector-initiated urban development has been characterized by two general approaches namely coastal reclamation and urban redevelopment.

Both involve the production of new urban space—the former, by creating land where none previously existed, and the latter, with the clearing of old structures to make way for new ones. Either strategy is employed to take advantage of new market opportunities, new infrastructure (e.g., transit systems), or new regulations (e.g., higher allowable FARs or reclamation policies).

Goals of redevelopment

The goals of redeveloping an urban location, however, are different from reclamation.

Redevelopment is often initiated to arrest urban stagnation or decay, to lift declining land prices, to address competitive pressures, to harvest latent land values, or to bring sub-optimally utilized properties to higher productivity. It is far easier to cite the reasons for redevelopment than to answer the question, “Redevelop into what?”

This was and remains to be the biggest challenge for urban redevelopment. Beneath the intent to densify, upgrade product offerings, rationalize a site’s use and function, improve economic performance, and enhance the place’s stature are nested questions: What will the place become? What will its transformation mean to people and surroundings?

While the root of any redevelopment and masterplanning effort lies in addressing economic and functional viability, its long-term significance relies on how the place will resonate with its users. It will be straightforward to plan another urban township by using a formulaic approach by recreating say a Rockwell or a Bonifacio High Street. But by doing so, will it have depth and enduring meaning, especially in an environment where most townships are trying to do the same?

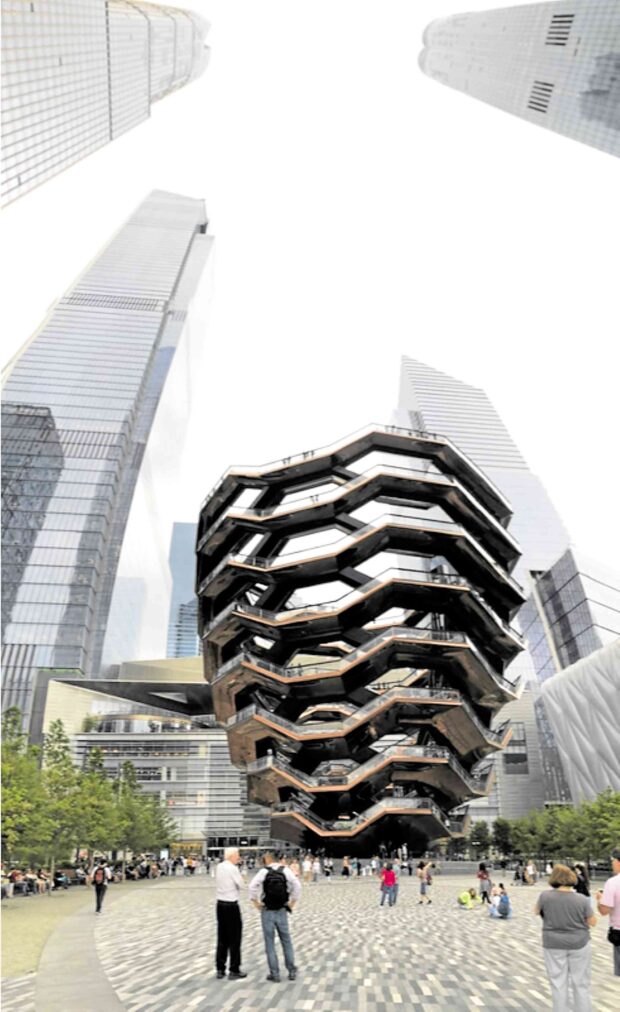

Hudson Yards in New York City is the largest private urban development project in the United States—claiming to be “the way New York as it should be”.

Generating more impact

Developers employ various strategies in redevelopment. Some opt to build incrementally, allowing a parcel to be developed one section at a time (as in the case of Greenbelt), while others redevelop entire blocks in one fell swoop (as in Hudson Yards, NYC).

The latter tends to generate more impact but can also attract controversy given the scale and suddenness of change, and tendency towards upscale urbanism and gentrification, thus reinforcing inequality in our cities. Whether done gradually or suddenly, redevelopment often involves displacement—the shifts in neighborhood commerce, composition, and aesthetics that reveal that one group or “community” has been “displaced” by another.

In the desire to capture users’ imaginations and to differentiate from competition, some developers appropriate buzzwords to their projects such as “smart city”, “global city” or “green city” or come up with fluffy value proposition statements that sound lofty and aspirational but devoid of meaning to the ultimate users of the places they will create.

More often, the implicit purpose of developments is reduced to the extraction of value rather than its creation, with success being measured by narrow metrics such as net income after taxes (NIAT), return on investment (ROI), gross profits, or sales per month.

For growth to be considered decent, it must compound annually, even if the resources that fuel such growth deplete. In a paper published in the Journal of Biourbanism, Architect Sergio Los of the University of Venice lamented: “Today we ask the landscape how much money can we make through it.”

Greenbelt in Makati City is a privately owned public open space that has been redeveloped in stages over the years. (PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR)

This is the question that is asked not only because economic yield is a prime consideration in any real estate undertaking, but also because it is easier to answer. More difficult and nuanced is the question, “How much prosperity can be generated by this place?” This is hardly asked in board rooms of the key agents of urban development in our cities, even if this is what captures the true economic role of urban areas.

Purpose of place

Cities and the places within them are ultimately about the public life they create. Long after financial targets have been achieved and the returns on investment realized, generations of people will live and work in the environments we build.

We need to see beyond superficial tactics such as making places “instagrammable” or “TikTok-friendly”. Instead, we should ask questions like, “What stories will people say about the place? What memories will they create? How will the place inspire their lives and allow it to flourish?”

These may seem like naively romantic notions about the role of cities, but in the overall scheme of things the purpose of place depends on the kind of questions we ask ourselves before creating it.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning and design consultancy practice