Urban planning is guided by desired trajectories that are based on a clear understanding of what a city is and how it comes to form. It involves decision-making and envisioning what the city may become given a range of opportunities and constraints.

Vision-led planning entails imagining beyond the obvious and outside of what has been tried in the past, with the end goal of seeing alternative futures.

Urban spaces need to be sustained, renewed and rejuvenated through deliberate and directed interventions.

Live cities as planning units

A city is formed out of endlessly reconfiguring networks of interdependencies that make for vibrant and robust spaces.

Urban areas develop over many years through processes of agglomeration and territorial definition. Cross-border encounters enable cities to fulfil their production and efficiency goals. A city is alive and, as an organic entity, goes through a life cycle that leads to development or decline.

As such, urban spaces need to be sustained, renewed and rejuvenated through deliberate and directed interventions. For life in and of cities to be sustained, interdependent elements need to be kept in a balanced state as different forces challenge the status quo. The city’s evolving form is reflective of the adaptive processes that ensue as places, people and events interact.

Cities and places in general, are set amid dynamic contexts and not all future scenarios may be predicted. Plans for the next 30 years or so, however, may be anchored on the certainty of the following realities defining the decades to come: convergence and densification, globalization, climate change, digitalization, and territorial conflicts.

With these as the givens, decisions need to be made now for cities to get through other unexpected stressors.

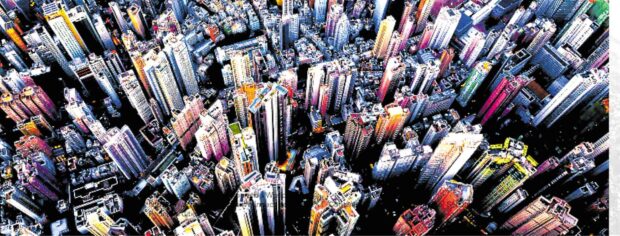

City governments globally have made conscious decisions in favor of compact urban settings defined by vertical developments.

Convergence and densification

Notwithstanding all the realizations in recent years that saw the shift to virtual spaces and online interactions, cities as spaces for physical convergence will remain relevant.

With life quality consequences and carrying capacities as considerations, policy decisions on concentration or de-concentration will determine where people will be moving towards. Enabling further densification supports efficiencies due to economies of scale, but this can also lead cities to their tipping points beyond which inefficiencies will begin to manifest.

City governments globally have made conscious decisions in favor of compact urban settings defined by vertical developments. Others have directed investments in infrastructure outside crowded cores to encourage people to settle in new centers.

Globalization

The global production and distribution system will continue to underlie the roles of cities in an integrated economic network.

With the pressure to conform to international standards comes the need to decide on the extent to which cities will rebrand to be competitive in the global arena. The entry of foreign direct investments translates to land use changes that trigger movements of both the financially able and socially marginalized. Without deliberate planning and well-thought-out interventions, who remains and who gets driven out of the serviced city centers would largely be determined by the laws of economics.

Being global also entails measures that guard against the loss of place identities and heritage. As cities struggle to fit into the international mold, they can also rely on soft power anchored on culture.

Decisions need to be made now for cities to get through other unexpected stressors. (GELOY CONCEPCION /HTTPS://NOLISOLI.PH)

Climate change

Rising sea levels, changes in temperatures, and extreme events will impact urban form and lifestyles.

The spatial disposition of residential and economic bases will reflect the confluence of nature-driven choices and market-led decisions. With the latter often challenging nature and consequently putting the vulnerable sectors of society at risk, regulations must be enforced to direct activities to safe and low-risk areas.

Cities are at most risk because of the combined effects of typically coastal location, population size and building density. While land use plans and zoning ordinances reflect long-term policy decisions that direct building and development trends, these regulation tools should also allow flexibility that will enable cities to adapt to unforeseen events.

Digitalization

With the inflow of information and technology that can radically change our concepts of cities and urban spaces comes the need for calibration and critical application.

Automation of services imply labor profiles and location distributions. The so-called digital divide will manifest in a redefined concept of distance that is based on abilities or inabilities to access information and services. While proximity to enabling factors has long been based on travel distance to city centers, digital literacy and access to gadgets will be key to people empowerment.

Cities are at most risk because of the combined effects of typically coastal location, population size and building density.

Territorial issues

Conflicts over cultural and physical boundaries are realities that will have to figure in plans for the cities in the Philippines.

Whether disruptions are triggered by external or internal aggressors, provision of basic needs in conflict areas cannot be relegated to low priority status. Families caught in the crossfires must not be left to fend on their own in terms of accessing food, livelihood and shelter. Access mechanisms for land ownership and housing will have to be crafted with threats and risks factored in. For example, funding windows offered by the government should identify alternatives to loan guarantee concepts that rely on collaterals and formal employment.

Buffering the effects of disruptors

As cities navigate through changes brought about by foreseeable and unpredictable factors, the disruptive effects may be mitigated through vision-led planning. Visualizing the city’s future must take into account urban ecologies that are defined by people, the built and natural environment and economic systems.

The author is a Professor at the University of the Philippines College of Architecture, an architect, and an urban planner