The masterplanner’s dilemma

The engagement of a masterplanner is often among the first steps undertaken by property developers when pursuing a project of significant scale and complexity.

The goal is often straightforward, yet daunting: to arrive at the highest and best use for the property. It is also a goal that is ultimately unachievable in the ever-shifting context of an un-static world since the highest, best use is only applicable to a very specific set of circumstances and timeframe.

The expectations on the outcome of masterplanning large-scale developments imply the omniscience and omnipotence of the masterplan—and therefore, of the masterplanner.

This provokes the question on the nature of cities: do cities come into being or are they constantly in a state of becoming? If it is the latter, then masterplanning will ultimately be futile as there is no end-state that can be foreseen, much less predicted.

Divining the future

The process of evolution is often gradual and incremental, involving the piece-by-piece and building-by-building realization until a sense of wholeness is attained. This thus presents a temporal dilemma: how can a single vision transcend time?

The problem is in the belief that the masterplan is the key defining element that can steer change rather than the reality that the urban outcome is the result of a constellation of random elements, multiple factors, and shifting contexts that cannot be captured in a single codified plan.

In the end, aren’t our idealized masterplans simply rationalizations of momentary stages that strive to persist in what Architect Rem Koolhaas calls “a landscape of increasing expediency and impermanence”?

Masterplanning requires the determination of a preferred long-term outcome for a particular location out of a multitude of possibilities. This requires keen knowledge of the myriad forces that shape cities to sieve through scenarios until you arrive at one with the best chances of success.

In the end, most masterplans do not attempt to predict the future, but audaciously aim to shape it. Such is the thinking behind the grand visions of masterplanned cities like Chandigarh, Brasilia, Putrajaya, Reston, and many others whose realization had its share of challenges. The appeal of creating an entire modern city from scratch is compelling but its realization requires sheer will, tremendous effort, and huge costs.

Visionary plans

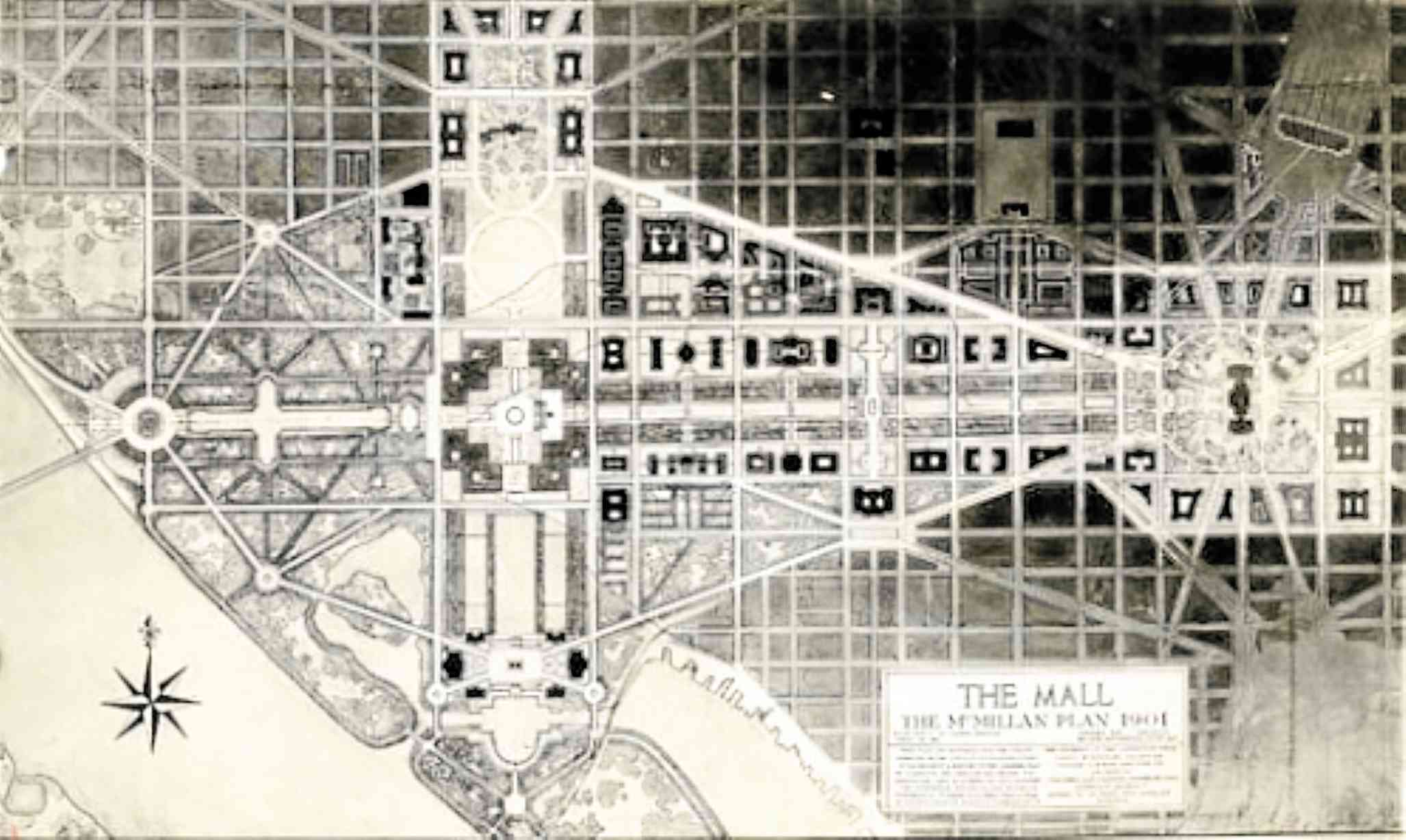

Some visionary plans for cities have proven to be enduring—Cerda’s Barcelona, L’Enfant’s Washington DC, Haussman’s Paris—implemented plans that have remained largely intact when numerous other places have succumbed to highways, malls, high rises, and urban renewal.

While the visionary genius of these planners cannot be denied, the resilience and seemingly unchanging nature of these cities despite shifting socio-economic and political contexts were not solely due to the planners’ mettle. Preservation of these urban settings was largely by edict through stringent zoning and building codes that push new development elsewhere to preserve the envisioned urban form.

These codes take many forms—from land use ordinances to restrictive covenants and urban design guidelines. They, in effect, codify the genome of the masterplan, allowing the original vision to be interpreted and expressed in the design of individual parcels and buildings to achieve a level of conformity and consistency even if such buildings are crafted by many hands and minds over long timeframes.

The intent is to establish and perpetuate some aspired imagery or expected experience, frozen at the time of the plan’s finalization. The ideal is to achieve a cohesive and unified collective outcome that still allows for sufficient variegation, creativity, and individuality. As writer Mary Ganis pointed out, “Building cities is a concrete business that is trapped in a shifting context.”

But these codes’ limitation, just like the masterplans they are part of, lies in their inflexibility. Because they are designed to resist change by codifying the urban design vision, they will fail to address and respond to future unknowns.

Rigid masterplans

A rigid master plan can fall into a Procrustean trap. It can entrench outdated thinking, reduce a location’s resiliency, and limit future opportunities and constrain innovation.

Prescribing a future state for a place can become an exercise in imposing a form of control which may or may not serve interests in the future. How do you then arrive at an adaptive spatial framework when the goal of masterplanning is of achieving permanence and predictability?

The ideal urban plan is one that has a capacity for long term equilibrium, adaptability to shifting market forces, as well as resiliency in times of short, sharp crises in both the immediate and distant time scales.

That the future is ours to control is a biased and arrogant approach to masterplanning that ignores the possibilities, actualities and needs of the future, failing to acknowledge that not everything can be anticipated in a comprehensive masterplan.

Constant state of ‘becoming’

At best, the masterplan points a trajectory towards a desired goal—a framework where current needs are addressed through more prescriptive short-term planning which, in turn, is embedded within a long-range plan that is deliberately flexible and adaptive.

It will necessarily have to be suggestive except for the most essential elements of its infrastructure. It recognizes that the city will be in a constant state of becoming, crafted over time by many actors with varying imperatives. It will never be exactly as the original visionary planner foresaw, but instead will self-organize according to the rich complexity of urban change.

Its success will be in how the masterplan is able to fit the changing circumstances of the times, assimilating varying contexts, constantly morphing into something new. This is how a city can be perceived as being always of its time and of its place.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning consultancy practice. Visit www.jlpdstudio.com