ECONOMIC TEAM Trade Secretary Alfredo Pascual (left), Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno, National Economic and Development Authority Secretary Arsenio Balisacan and Transportation Secretary Jaime Bautista briefing the media in Davos —DORIS DUMLAO-ABADILLA

The Philippine Development Plan 2023-2028 is not the first economic blueprint for the country that was drawn up in the wake of economic, historical, global upheavals.

We had a “technical memorandum” on Philippine Economic Development adopted by President Roxas for the years 1947-1952 at a time of rebuilding immediately after World War II.

The Roxas administration built on up such a memo and drew up a more proper plan, but it was the succeeding Quirino administration that carried it out. This was the five-year (1949-1953) “program for rehabilitation and industrial development,” also known as the Cuaderno Plan after Mr. Roxas’ Finance Secretary Miguel Cuaderno Sr.

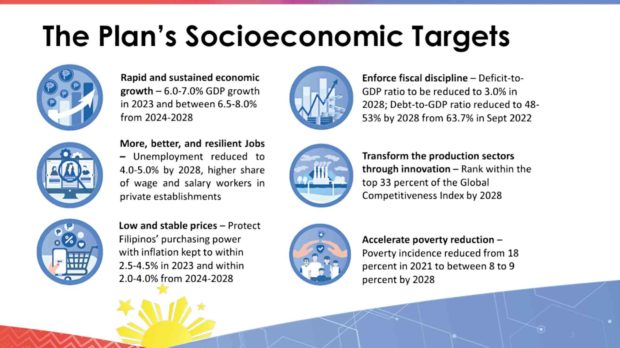

Through the intervening decades, economic road maps sought to increase national output and income which—when later plans were improved with a broader perspective that integrated the “social” aspect in planning—were to be measured in terms of job creation, human development, equitable distribution, poverty alleviation (and later on, reduction), and even good governance and the rule of law.

The latest iteration of a Philippine economic blueprint, PDP 2023-2028, was drawn up amid the lingering disruptions of a global pandemic.

“By taking stock of the many lessons we have learned from the past three years, the PDP clearly and coherently maps out our vision, timeline and strategies for deep and genuine socioeconomic transformation,” says Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno.

Considering this, Secretary Arsenio Balisacan of the National Economic and Development Authority says that the plan not only entails support for human and social development, it also includes protection from risks and preparation for future economic disruptions.

Competition and prices

Balisacan says the PDP strategies will also include transforming the production sectors so that they can provide a range of goods and services at competitive prices, especially at a time when high inflation is a pressing problem.

“This entails creating an enabling environment for growth and investment through policies that foster competition and innovation, harness digitalization as an efficient means of delivering public and private services, and uphold peace and security,” he says.

For the economic or production sector, the plan is geared toward modernizing agriculture and agribusiness, revitalizing the industry sector and reinvigorating the services sector.

ROAD MAP The latest edition of the Philippine Development Plan, which covers the period from 2023 to 2028, improves on previous gains and applies lessons from COVID-19 crisis, according to the Marcos administration’s chief economist.

For the social and development part, the plan is intended to promote and improve lifelong learning and education, boost the population’s health, establish livable communities, ensure food security and proper nutrition, strengthen the social protection system, and increase the income-earning ability of the workforce.

To catalyze the economic and social strategies, the plan is banking on digitalization, public-private partnerships (PPPs), “servicification” or building ecosystems around manufacturing clusters identified as potential sources of high growth, a dynamic innovation ecosystem with new products and more efficient processes, enhanced digital and physical connectivity through infrastructure and greater collaboration between the national and local governments.

To entice investors’ support in the implementation of the plan, this was promoted recently through several economic and business fora held in Germany, the United Kingdomand Japan.

In these fora, the Marcos administration touted a large consumer base of over 110 million people in an economy that expected to reach upper-middle income status in the next three years.

The Philippines is pictured as a competitive launching pad for the Southeast Asian market which is, in turn, a market with more than 600 million people.

Also, the administration rekindled attention to the Philippines’ “demographic dividend” —a growing and young working population that presents fuel for additional sources of economic growth in the next two to three decades.

More importantly, the country is presented as now being more open to business than ever before, thanks to new laws that liberalize domestic industries.

The Marcos administration vows to build on such “game-changing reforms” in the investment environment, such as the amendments to the Foreign Investment Act, Retail Trade Liberalization Act, and Public Service Act, as well as the passage of the Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises Law.

Thus, there are significant opportunities for PPPs in energy, water, logistics, transportation, agribusiness, tourism, health, education, and digital connectivity.

In this regard, the Marcos administration promises to strengthen and facilitate PPPs, trade and investments, research and development, and technology transfer, while enabling open and competitive markets will complement these reforms.

Protecting consumers

The goal is to make it easier for companies to compete and innovate while upholding consumer protection. Businesses will be assured of lower transactions costs, a healthy regulatory environment, and protection from anti-competitive practices.

And as the Philippines seeks to “regain its position among the most dynamic economies in Asia and the world” through the plan, Balisacan says PDP has provisions to strengthen the resilience of communities, institutions, and ecosystems to the impacts of natural hazards and climate change.

Neda’s imperatives

“To achieve transformation, we must introduce systematic changes to our consumption and production patterns, as well as manage our natural capital resources, if we are to sustain a well-functioning and resilient economy,” the Neda chief says.

“Indeed, given today’s technological advances, sustained levels of high growth need not be at the expense of the environment,” he adds.

At the same time, Balisacan says the administration is reaffirming the commitment to significantly reduce poverty and inequality in the Philippines through the PDP, which he described as designed to address the persisting multi-generational inequality and poverty among Filipino families.

“In particular, initiatives to boost health, improve education and lifelong learning, increase income-earning ability, ensure food security and proper nutrition, and rationalize social protection will be among the main policy thrusts of the PDP,” he says.

“We aim to sustain the socioeconomic gains in the past decade for at least two more decades, in the hope of attaining the AmBisyon Natin 2040, which states that all Filipinos will enjoy a firmly rooted, comfortable and secure life by 2040,” he adds.

This was brought up as the World Bank reported that the top 1 percent of Filipino earners contribute to 17 percent of national income while only 14 percent comes from the bottom 50 percent.

“We must urgently address these challenges so that we do not backslide and instead sustain our efforts towards sustainable and inclusive economic development,” the Secretary says.

But research group IBON is not impressed, dismissing PDP 2023-2028 as a rehash of a worldview that was becoming obsolete and one that needed to be reversed.

The group said that through the years, PDPs have had the same framework and have made the country more and more export-oriented and attractive to foreign investors by opening up the economy.

Despite this, IBON said the share of manufacturing has fallen to its smallest share of gross domestic product since the 1950s while that of agriculture shrank to its smallest share in Philippine history.

For the think tank, the latest PDP will not deliver more, better and green jobs, nor will it drive progress.

“The PDP is underpinned by an out-of-date free market globalization framework which is the very same approach that kept the Philippine economy persistently underdeveloped for the past decades,” IBON said.

“Changing global conditions of dampening exports and investments only point to the urgency of much more domestic-led and democratic development,” it added.