Billionaire businessman, technocrat, political operator Roberto Ongpin dies at 86

Businessman Roberto Ongpin. INQUIRER FILE PHOTO

Updated @ 1:32 a.m., Feb. 6, 2023

MANILA, Philippines — Roberto “Bobby” Ongpin — the accounting firm head who was drafted to serve as one of the top government ministers during the Philippines’ worst economic crisis, later becoming one of the country’s wealthiest and most influential businessmen —bhas died.

According to close relatives and associates, he passed away in his sleep on Sunday in Balesin Island, the exclusive resort club he built. He was 86.

“It is with profound sadness that I provide this update, something I wished I would never have had to do,” said Rodolfo Ma. Ponferada, president of Alphaland Corp., in an email to Balesin’s members. “Our chair and founder, Roberto Velayo Ongpin, passed away peacefully in his sleep early this morning, 5 February 2023. As many of you may know, he had just turned 86 years old last January 6.”

“[Ongpin] was husband to Monica, father to Stephen, Anna, Michelle and Julian, father-in-law to Laura and Frank, and in what I believe to be his most cherished role, grandfather to Sebastian, Benjamin, Lia and Maya,” Ponferada said.

In May of last year, Ongpin showed to the Inquirer several chapters of the “tell-all” memoirs he was writing, detailing his long and colorful life in government and business. He said then that he was leaving explicit instructions that this book be published only after his death.

Job interview with Marcos

Ongpin, born 1937, began his professional career as an employee of the country’s top auditing firm, Sycip Gorres Velayo and Co. (SGV), in 1964.

He was a graduate of the Ateneo de Manila University where he earned his bachelor’s degree in business before receiving his master’s degree in business administration from Harvard University.

He had recalled to the Inquirer that, during his interview, one of the company’s founders, the late Washington Sycip, asked him what was on his mind, and Ongpin replied: “I’m thinking about how long it will take for me to sit there,” pointing at Sycip’s chair.

Two years later, Ongpin was named SGV managing partner, the firm’s youngest ever, serving until 1979 when he got a phone call ordering him to come to Malacañang Palace for, as it eventually turned out, a job interview with then President Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

After demurring a couple of times, saying he was too young and inexperienced, Ongpin accepted Mr. Marcos’ offer to head the Ministry of Trade and Industry on condition that he be given direct access to the President and a free hand at trying to reform key aspects of the economy which, at that time, was already starting to show strains from domestic problems and a global recession.

“When a President asks you to serve, you say yes,” Ongpin said then.

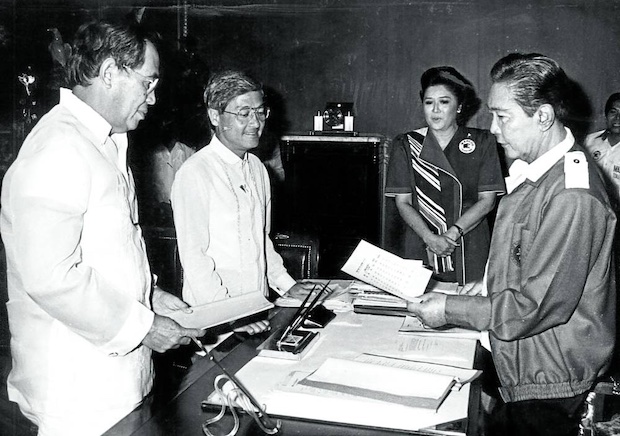

‘WHEN A PRESIDENT ASKS YOU TO SERVE, YOU SAY YES’ | Roberto Ongpin was 42 when he was called in 1979 to serve as trade minister in the Cabinet of Ferdinand Marcos Sr., which also included Energy Minister Geronimo Velasco (leftmost of photo) and Imelda Marcos as human settlements minister. In his crucial post, he presided over an economy in crisis and also resisted policies which favored cronyism. (INQUIRER FILE PHOTO)

Behind closed doors

As Marcos’ top technocrat, one of the key roles Ongpin played behind closed doors was to block self-serving policy recommendations from Marcos cronies which he felt would be detrimental to the Philippine economy.

On more than one occasion, the young Cabinet official went to Malacañang to explain to the President the ill effects of executive orders he had issued, supposedly at the behest of close associates—orders to allow importations, grant loans, or support struggling companies—and have them rescinded. And according to Ongpin, “sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t.”

One of the biggest roles he played during that time was setting up and running the so-called Binondo central bank, which was created in response to the shortage of dollars needed to pay for imports after the country’s 1983 sovereign debt default.

At Ongpin’s direction, police rounded up seven of the biggest Binondo-based foreign exchange traders—waving at them a presidential authorization to have them incarcerated if they refused to cooperate—and ordered them to sell only to the government (at a capped profit) all the dollars they could buy from the market.

These dollars were then used by the government for its foreign exchange requirements such as buying imported medicines and infant formula.

After Edsa

After the Edsa People Power Revolution, Ongpin was accused of personally profiting from the scheme, but the charges never stuck and he was cleared of wrongdoing. Even his right-hand man in the Binondo central bank, businessman Willy Ocier—who later became a business rival—told the Inquirer that Ongpin never profited from the foreign exchange operations.

“Not a single centavo,” said Ocier, whose father was one of the big money changers who were forcefully drafted into the operation.

A few years later, Ongpin struck up a friendship with Malaysian businessman Robert Kuok and convinced the latter to make a significant investment in the country—the Edsa Shangri-La Hotel which opened in 1992 and a shopping mall in Mandaluyong City.

With his business empire resurgent during the Arroyo presidency, Ongpin became a target of a government investigation during the presidency of Benigno Aquino III.

He was accused of borrowing P660 million from a state bank to buy shares in Philex Mining Corp. which he then sold to businessman Manuel Pangilinan soon after for a profit.

Despite having fully repaid the government loan ahead of schedule, Ongpin was accused at various points in the probe of profiting from a “behest loan” and engaging in insider trading.

All charges against him and his coaccused were dismissed after a long running Senate probe on live television and an eight-year legal battle.

Ongpin’s final hurdle came in 2016 when then President Rodrigo Duterte unleashed a tirade against the businessman, labeling him an “oligarch,” which resulted in his gaming firm Philweb Corp. being unable to renew its license. He was forced to sell the company as its stock price collapsed.

Averse to wealthiest list

Even after those episodes, Forbes Magazine, in its 2023 ranking of the country’s wealthiest individuals, listed Ongpin as the 23rd richest in the country with an estimated net worth of $830 million, declining from a peak of $1.7 billion three years prior.

The businessman had always protested his inclusion in the list, telling the Inquirer that he had written Forbes several times asking to be excluded from the ranking because it overstated his wealth.